This blog was written by Rajalaxmi Singh, PhD candidate at the Centre for Development Studies (Jawaharlal Nehru University), Kerala and Ricardo Sabates Aysa, Professor in Education and International Development at the Faculty of Education, University of Cambridge.

India has made substantial progress in achieving universal enrolment in primary education, with almost all children being enrolled in school. Nonetheless, learning remains a challenge, particularly in rural areas. As shown by the ASER Report in 2022, half of children in Grade 5 in rural primary schools are unable to read at the level expected for Grade 2. This raises the question: who is accountable for the lack of learning that is taking place in schools?

A school’s primary responsibility should be to the children living in their local communities, and the responsibility is much more than just enabling access. Supporting a deep understanding of the content of the curricula, skills formation, enabling a sense of belonging to the community, as well as formation of peer and social relations, should all be equally prioritised by schools. Parents play an important role in enabling the schools to holistically support their children. Parents support their children with knowledge, time and resources, particularly at home and in their communities, which enhances and complements school provision. Parents can also support school through the lenses of accountability, making sure that schools comply with the provision that is required and mandated by the government and/or educational authorities.

As discussed by Joshi (2014), models of accountability start with the premise that all educational actors perceive children’s education from the same principles, using the same analytical lenses, and potentially discussing common solutions. However, it is not always clear whether parents perceive education in the same way as head teachers or teachers, and whether their involvement supports the provision from schools. How parents frame the concept of learning is central to how they support their children directly and importantly, whether parents consider the schools to be supporting the education for their children.

In the context of rural Uttar Pradesh, India, to what extent do parents perceive that their children are learning in schools? Who are these parents and what is their involvement with school activities? To shed light on these questions, we use information from the “Accountability from the Grassroot” project led by the ASER Centre in New Delhi in collaboration with the Research for Equitable Access and Learning (REAL) Centre, at the University of Cambridge. Information came from 19,286 children selected from 848 government primary schools in 2018. These children were enrolled in Grades 2, 3 and 4 and were identified using the ASER tool for literacy as being unable to read simple words in Hindi. For all these children, we have information about parental perceptions on children’s learning as well as parental involvement in school activities. Additional socioeconomic and demographic information of the households was also collected.

Parental Perceptions: 35% of rural parents perceive their children to be able to read their textbook

We asked the question “Can the child read his/her textbook easily?” to the main carer (in general, mothers) in each of the households where children live. We discuss responses in terms of ‘parents’, acknowledging that this relates to the main carer. We find that 35% of parents perceive that their children were able to read their textbook easily. From the use of the ASER tool, we have identified all children in our sample as not being able to read simple words. Therefore, over one third of parents overestimate the reading skills of their children or perceive their children able to read their textbook easily when they are not able to. We may question whether these parents have different understanding of what “reading a textbook easily” may mean and if under this lens they perceive their children to be able to read.

On the other hand, the majority (57%) of parents responded that their children are not able to read their textbook easily and a further 8% were uncertain as to whether their children are able to read their textbooks easily.

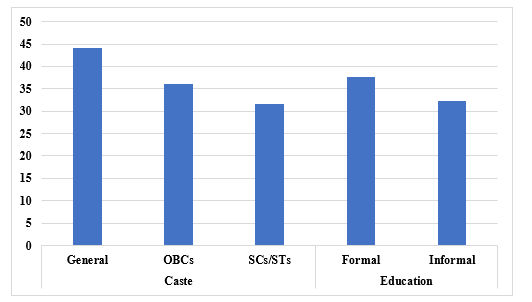

Focusing on the caste and educational backgrounds of the main carer, we found an interesting pattern. Parents who perceive their children to be able to read their textbooks easily were more likely to come from general caste and to have had experience of formal education. As Figure 1 demonstrates, nearly 45% of parents from general caste perceive their children to be able to read, and this is approximately 8 percentage points higher than other backward classes (OBCs), and 13 percentage points higher than scheduled castes (SCs) and scheduled tribes (STs) . Similarly for educational background, there is a difference of 6 percentage points in favour of parents with an experience of formal education to perceive their children to be able to read their textbook.

Parental Involvement: Parents who perceive their children to be able to read are more likely to be involved with the school

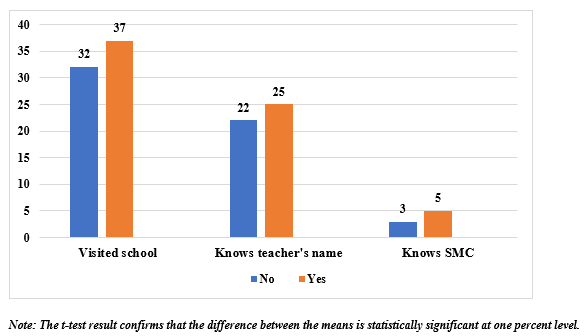

We asked the main carer whether they have visited the school during the current academic year to discuss the child’s progress, whether the parents knew the name of any of the child’s teachers and whether the parents knew about the School Management Committee (SMC). We use this information to assess whether parents who perceived their children to be able to read their textbook were more likely to be involved in these activities, relative to parents who did not perceive their children to be able to do so.

Interestingly, we find that parents who perceive their children to be able to read their textbook were relatively more involved in the three different school-based involvement activities. Figure 2 illustrates that 37% of parents who perceive their children to be able to read their textbooks also visited the school to discuss the academic performance of their children. For parents who perceive their children not be able to read their textbook, only 32% of them visited the school.

We also know that parents from relatively higher socio-economic backgrounds, for example higher caste, wealthier and with experience of formal education, are more likely to be involved in school-based activities. For example, over 40% of parents from general caste visited the school to discuss children’s progress and just less than a third of parents from OBCs, and SCs/STs visited the school. Similar trends hold for parental wealth and education as shown by Cashman et al. 2020.

Reflections through the lenses of accountability

Our findings raise an important question about the role of perceptions of stakeholders in accountability models. First, a significant proportion of parents perceive their children to be able to read, when based on the ASER tool, these children are unable to read simple words in Hindi. One may consider that the misalignment between parental perceptions of children’s literacy levels and the children’s actual literacy competences is aspirational. In other words, the child demonstrates some ability to read, and hence parents respond with high aspirations in terms of their child being able to read. Alternatively, the misalignment may be for a socially desirable response. In other words, given the higher caste or social position, the response of parents indicates a position of advantage (i.e. the child is able to read). Whether aspirational or to have desirable response, a significant proportion of parents are perceiving children’s education differently, hence impacting the basis for potentially discussing solutions with school stakeholders.

Importantly, parents who perceive their children to be learning are also more likely to be involved in school activities. These are also the parents who have the cultural capital to discuss issues of academic progress with teachers. Yet, these parents seem to perceive their children to be able to read, hence this raises questions about any actions that these parents may take in terms of holding the school accountable for the lack of academic progress. As discussed by Ramachandran (2004), parents from disadvantaged backgrounds often feel themselves incapable of engaging with schools, and in our case, these are the parents who were more likely to perceive that their children were unable to read. Unless there are common understandings of the role of different stakeholders in supporting children’s education, what is meant by learning, and a sense of mutual responsibility, raising learning outcomes in rural India is likely to remain a challenge.

————-

Acknowledgements: Funding for the data collection and the research was provided by the UK Economic and Social Research Council (ES/P005349/1) and for the accountability activities in Uttar Pradesh from Wrigley Company Foundation.