This blog was written by Mireia Gil. Mireia is currently completing her PhD about the impact of education policy in the young people pathways in the suburbs of Dakar, Senegal in Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona in Spain, alternating it with her work in the development and humanitarian field. For the 2023 UKFIET conference, 28 individuals, including Mireia, were provided with bursaries to assist them to participate and present at the conference. The researchers were asked to write a short piece about their research or experience.

Over time, education policy has been affected by external factors embedded in the very process of (de)colonisation, as well as in an international scene in which multi-scalar actors promote diverse projects to change the education system. Against this background, it is uncertain to what extent the actual implementation of education policy comes from the state’s own will, which is often subordinated to external pressures at various stages of decision-making.

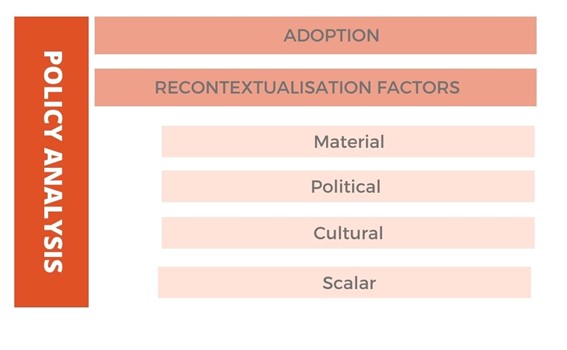

1- The key factors

In Senegal, primary enrolment rates have increased considerably in the last decade. However, learning and access to further education remain stagnant. International political economy points to certain factors that influence on how governments implement education policies. A set of material, political, cultural and scalar factors recontextualise the educational agenda as international political economy influences the approach:

Author’s own elaboration based on Verger; Novelli, Altinyelken 2012 “Global Education Policy and International Development: An Introductory Framework

First, material factors normally constrain the potential of education in low-income countries, However, Senegal spends almost 6% of GDP on education and has a low pupil/teacher ratio in the African context. So, this factor does not seem to be a determinant.

Second, political and scalar factors make a big difference. As an aid recipient, the government is linked to many donors. Donor interests normally reflect the former colonial relations with France and the current configuration of export markets (Menashy, 2019). In general, all the countries of the West African region, particularly the French-speaking ones, have to comply with certain conditions in order to receive funding or capacity building. Eventually, the French Agency for Development, the World Bank, UNESCO and the Global Partnership for Education reiteratively intervene on the main issues of education policy in the country. It is intriguing to inquire how these international organisations deploy their projects, which as Roger Dale noticed, derive from a complex institutional logic even if they are normally instrumentalised by the most powerful states (Verger, 2012).

Third, cultural factors also have a considerable impact on the Senegalese identity. Schools do not foster human capabilities for their own sake but have become a space located far away from the child’s culture (Sriprakash, 2012). In African countries, after decolonisation the school curriculum keeps devaluing the history of African empires, concealing the impact of colonisation and slavery and overlooking the creation of a common spirit of ‘country’ amid the multi-ethnic, multi-lingual make-up of the state. In addition, the language of instruction is not the mother tongue of students due to the difficulties of teaching a variety of languages in the same academic environment, French has become the only language of schools.

2- Who rules?

As discussed above, the Ministry of National Education (MEN) is responsible for the coordination of education but it is influenced by global national and local actors. International organisations, cooperation agencies of other countries as well as international NGOs and other international platforms are extremely influential in the West and Central African region. On the other hand, some NGOs , civil society organisations, private companies and individuals influence decision-makers at the national, regional and local levels as well as in schools themselves.

3- What is the official policy?

The MEN has established a long-term strategy in the Programme for the Improvement of Quality, Equity and Transparency, Education Sector Plan (PAQUET-EF, 2013-2030), which expects to achieve that “the population accepts the orientation of education and training; to provide access to education for all; to adapt the system to the needs of the students; to provide adequate resources in relation to existing needs“. The PAQUET-EF aims at restructuring pedagogy towards quality, and enhancing the professional capacity of teachers’, at the same time as building schools and basic infrastructure.

The MEN runs the systems by means of circulars on the key aspects of school organisation although diverse actors have built the facilities and manage the schools. Despite the ambition of this plan, the outcomes are not satisfactory. Since 2013, the PAQUET-EF has not yet included private schools, which account for more than 40% of students in Senegal (OECD, 2018). Quality is also disappointing since only half of pupils completed compulsory secondary education in 2022, that is, the other half is unlikely to have achieved a minimum level of learning (RNSE, 2018).

4- Issues for education policy to consider

On the basis of the elements highlighted above, the question arises as to what education policy should aim to achieve, bearing in mind first of all that this education policy is made with an eye on international interests, rather the needs of the Senegalese people. As we have pointed out, education programmes are a mixture of pedagogy and system organisation. A great amount of performance contracts and procedures demanded by financial partners often give little thought to the real problems of teaching and learning.

The effects of globalisation and neo-colonisation are a clear observation of the strategy for implementing education policy. Can the MEN itself make sense of its own policy? Is the current trend towards decentralised and autonomous management related to young people’s real educational pathways and practices at all? To what extent has Senegalese education developed forms of organisation, management and teaching that promote local culture and linguistic diversity? In brief, how is the MEN interpreting the main challenges of the SDG4 in order to be able to deal with the global issues in the Senegalese education system?