This article was written by Abdirizak Haybe Ali, Education Columnist, based in the Somali region, Ethiopia.

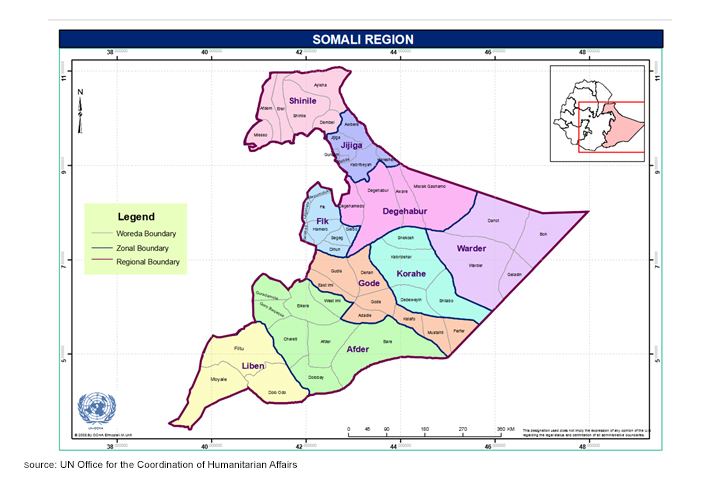

Looming drought is decimating the fragile lives and livelihoods of pastoral and agro-pastoral communities who live across the Somali region of Ethiopia. These communities rely on rainwater through access from boreholes, yet rain has persistently failed to arrive. Drought across the region is causing crop failure, livestock death, food insecurity, loss of family livelihoods and human tragedy leading to loss of life. It is also having devastating effects on education.

The basic infrastructure of the region has suffered over a protracted period due to historical and political isolation, as well as socio-cultural practices – all contributing to limited access and poor quality of education, and therefore ultimately, competent and knowledgeable citizens who can improve the development of the region and country.

The history of discrimination, marginalisation and isolation of the Somali region has persisted since the monarchal regime, resulting in severe consequences for education: including access constraints, the lack of a relevant contextualised education curriculum, isolation according to ethnicity, and better opportunities for non-Somalis dwelling in the region. There is little confidence from local communities for sending their children to school.

The Ethiopian education policy of 1994 reshaped the country’s education system by enabling regions to develop and use contextualised systems and the appropriate mother tongue as the medium of instruction in lower- and upper-primary grades (Grades 1-4 and 5-8), with English remaining the language of instruction for secondary level. Yet limits in access, irrelevant curricula and extremely poor quality of education have widely persisted across the region, causing learning barriers for those children eager to enrol for education opportunities.

With higher levels of poverty and increasing frequency and magnitude of droughts in the region, communities are less about to adapt and cope with hazards. The fragile environmental situation is teetering alongside an equally fragile education system. Despite expanding formal and non-formal education opportunities, delivering equitable, inclusive, quality education and improving children’s foundational skills remain key challenges.

Despite progress made in the Somali region more recently, the education pace is stunting due to the looming drought, and families having to divert attention to life-saving interventions. Currently, 1,867 primary schools have been hit hard by drought, with 382,403 children having their schooling disrupted. 45% of 4,134 primary schools have been affected and 33% severely affected by the drought. In addition, 598 schools have been damaged by strong winds due to the dry spells. The scale of the crisis caused 663 schools to completely close in the first half of February this year – 253 formal schools and 410 Alternative Basic Education schools, mostly catering to pastoral children. This equates to 150,139 children having their education disrupted, with the figure anticipated to soar owing to the magnitude of the drought. This academic year, a total of 1,086,407 children (448,028 of these girls) had enrolled across different grades (pre-primary, primary and secondary) across the region, but it is uncertain how many will remain enrolled for the full year.

Factors contributing to disruption in learning (drop-out, repetition, poor performance and low completion rates)

Climate-induced hazards and conflicts are the most common tragedy disrupting children’s continued access to learning. Multiple factors contribute to the dramatic numbers of drop-out:

Food insecurity: Chronic food insecurity and low levels of resilience amongst pastoralist and agro-pastoralist households mean they struggle to feed their children. School feeding programmes contribute largely to children’s enrolment and retention in schools. The World Food Programme was the largest across the region, including hard-to-reach areas, yet sadly, halted operations in early 2017 due to mismanagement by the regional government.

During crises, households have no choice but to pull their children out of school to engage in casual labour to generate income and help feed the family. These children may never return to school, resulting in a ‘lost generation’.

Critical water shortages: Water scarcity and inadequate supply within the school compound sabotages children’s enrolment and retention, and particularly discourages girls (in addition, many schools do not have gender segregated latrines). More than half of schools do not have access to safe and clean drinking water, which has a serious effect on students’ academic performance and attendance. Many end up with water-borne diseases as a result of unhygienic water.

Unconducive learning environment: Poor school infrastructure (including combined desks, a lack of latrines segregated by gender, overcrowding, etc.), low levels of teaching competency and inadequate curricula all dent the possibilities to deliver an equitable, inclusive and quality learning environment.

According to Early Grading Reading Assessments (EGRA), conducted across Ethiopia in 2010 and 2011 through USAID support, heartbreaking data results revealed that large proportions of students were not able to read. The federal government is determined to make changes, moving away from traditional teaching methods and mother tongue languages. The Somali region showed results below expected benchmarks for lower primary grades in foundational skills.

Building education resilience in the Somali region

Building education resilience is essential for the delivery of quality education. Responding to the scope and intricacy of the situation requires considerable government commitment, community participation and substantial regional, national and international investment in the sector. Integrating education with other sectors such as agriculture and livestock is important for building resilience in the region. An integrated disaster risk reduction strategy and management system are needed to implement long-term climate change adaptation measures. The government is integrating climate change education into the school curriculum through the adoption of a National Climate Change Education (CCE) strategy (2017-2030). Nevertheless, concerted efforts to engage civil society, business people, government and humanitarian organisations are crucial.

Better financing is needed for the education sector to deliver quality, inclusive and equitable education. Building education resilience in the Somali region requires comprehensive and multidimensional efforts to address drought-prone areas with resulting food insecurity, for example though linking the most affected households to the Productive Safety Net Programme (PSNP). Building resilience involves clear steps at all levels – individual, community and system-level – to continually map out and identify risks, vulnerabilities and capacities, and identify appropriate interventions to mitigate and respond to emerging hazards.

Recommendations for building education resilience

- The Regional Education Bureau must lobby the Ministry of Education to adopt a child-centered disaster risk reduction strategy and decentralise this down to the region to better tackle climate-induced hazards (from drought or flooding).

- Synergies must be built between the regional developmental sectors (like the Regional Education Bureau and Regional Disaster Risk Management Bureau) to engage and design community early-warning systems.

- Planning and coordination must be strengthened between schools, communities and districts (zonal and regional) to improve disaster prevention, preparedness, response and recovery. Communities cannot reverse the adverse impacts of hazards but could lessen the magnitude or harshness of the disaster by learning to effectively anticipate, respond to and recover from from climate-induced hazards.

- The Somali regional education should advocate for the Ministry of Education to implement a Comprehensive School Safety (CSS) framework, a global framework aimed at reducing risks of all hazards to the education sector.

- Schools should implement a broader adaptation of disaster risk reduction strategies and integrate this into the school curriculum.

- The Ministry of Education and the Regional Education Bureau need to allocate a more adequate budget to the education sector, incorporating resources for human and climate-induced crises.

Read this 2020 article from the same author: Lives worth living: Educating Ethiopia’s Somali pastoralists