This article is written by Abdirizak Haybe, Education Specialist, Save the Children International, Ethiopia.

Pastoralists live in areas often labelled as peripheral, remote, conflict prone, food insecure and linked with high levels of vulnerability. Despite pastoral areas playing a significant role in the national economy, very little consideration is given to pastoral development and policy-makers often neglect them, focusing instead on the interests of agriculture for urban people. This includes neglect of pastoral children’s education needs.

Pastoralist children living in Ethiopia need an inclusive policy, which stresses pastoralist education and fair financial allocation that will lessen and curtail the undermining barriers to delivering a relevant quality and inclusive education to pastoralist children.

The situation for pastoralist education

Pastoral communities of Ethiopia occupy 61% of the total land mass and 97% of Ethiopian pastoralists can be found in low-land areas of Somali, Afar, Oromia and SNNPR. The Somali region is the main home of pastoralists and nearly 85% of the population’s lives and livelihoods predominantly depend on a pastoral and agro-pastoral way of life. Pastoralists’ lives and livelihoods have always been affected by climate hazards. Yet despite the challenges, pastoralists maintain their old-fashioned pastoral systems and strive to manage the effects on their lives from climate change, market volatility, insecurity and conflicts within their region.

The Pastoralist Education Strategy, developed by the Government with the support of multiple stakeholders, engaged in the development of an education sector with noteworthy aims: to provide a contextualised curriculum with relevant and age-appropriate content for pastoralist children. This recognising of rights to education created a sense of inclusiveness for marginalised and disadvantaged pastoralist children. And this was seen as a stepping stone towards ensuring the rights of pastoral communities who had been under-served by the previous regimes.

Challenges for pastoralist education

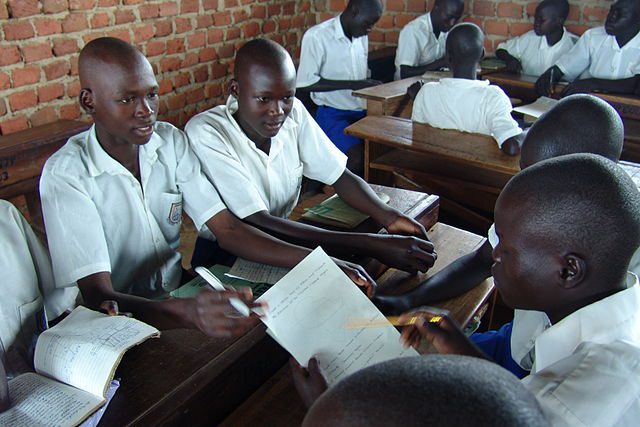

Local schools were set up in pastoralist areas, covering a range of lower primary education levels, particularly the first cycle of primary school (grades 1-4). However, many research studies stressed the persistence of poor quality of education, including:

- The poor economic status of pastoralists continues to limit their capacity to support the education system financially and materially.

- There is a low level of awareness about the importance of education and therefore a reluctance to send school-age children to learning spaces.

- The vulnerability of pastoralist areas to repeated drought and food shortage in turn forces students to drop out of school.

- There are high demands for child labour and engaging children in family and household chores.

- There are shortages of teachers and facilitators, and an absence of a variety of education delivery modes that are compatible with the lifestyle of pastoralists.

- There are acute shortages of teaching and learning materials and teaching aids produced for primary schools in pastoral areas.

Despite these challenges, educating pastoralist children can contribute a substantial amount to pastoral household incomes and it is important to encourage pastoral parents to send their school-age children to the public learning spaces/schools.

Increasing inequality divide due to COVID-19

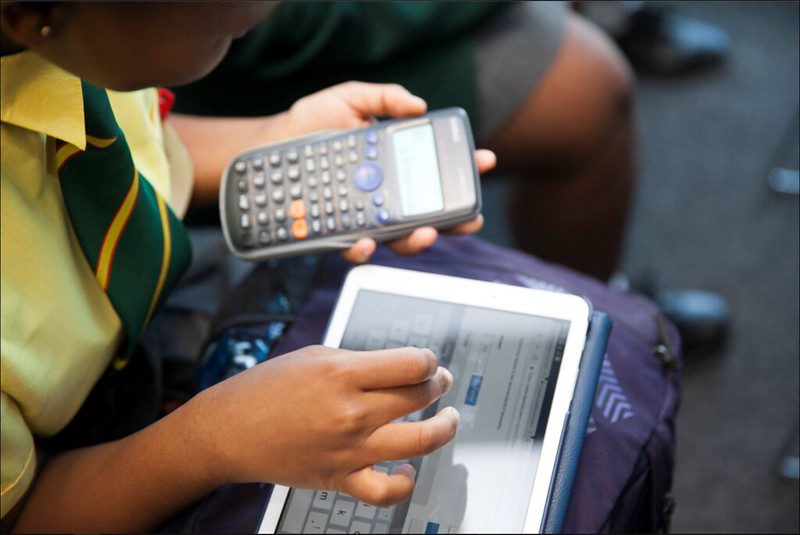

The persisting prevalence of poor quality education for pastoralist children has been aggravated by the global COVID-19 pandemic, which has reshaped the education learning space from traditional classrooms to digital learning. These structural learning shifts have resulted in increased learning inequalities between rural and urban settings. As a result, the COVID-19 virus has created a new unexpected challenge for pastoralists, to add to their compounding ongoing challenges.

As part of efforts to contain the spread of the coronavirus, public spaces such as schools are closed. Closing schools intended to minimise risks of spreading the virus and ensuring the safety and wellbeing of children. But learning has been disrupted for children and the continuation of education has become a paramount aim of the Government. This has been navigated through alternatives, such as the use of digital technology (TV and radio), but disparity in access to technology has only served to widen inequality gaps between rural and urban settings, due to the availability and affordability of the technology.

Pastoralist children are severely impacted by the new paradigm shift to digital learning using television or radio, due to the cost. Without access to the technology, they also lack access to the latest information about COVID-19 and how this affects them and their livestock. In urban centres, where infrastructure and facilities are better, children have accessed and benefited from digital learning. Yet in pastoralist settings, children have been unable to continue with their learning without access to devices.

Although pastoralists contribute substantially to the overall national economy and to government revenues through, for instance, taxes on their livestock, they do not benefit from investment in their education.

What can be done to ensure learning resumes and continues?

It is imperative for the Regional Education Bureau and partners engaged in the education sector to explore viable approaches for enabling pastoralist children to have decent and relevant opportunities that will compensate for their missed learning during school closures. Education for pastoralist children needs to be accorded the same official recognition and status as formal government schooling elsewhere, to avoid these children being further marginalised. In addition, the sensitive issues of safe and accessible water supplies and food security within the school premises need to be addressed as these have a huge impact on schooling opportunities for children in pastoralist areas. School hygiene and sanitation to help avoid the spread of COVID-19 (such as disinfecting of learning spaces, availability and accessibility of sanitisers, and facemasks), are considered essential to mitigate the spread of the virus within schools, yet not available in pastoralist learning spaces.

Provision of remedial and catch-up classes will be essential when schools reopen, even though, pastoral children whose education has been disrupted may never return back to school. Combined efforts will be needed to ensure that children resume and sustain their learning. Community sensitisation via a large back-to-school campaign, will be the best way to get families back on board. At the same time, delivery of an equitable, inclusive and quality education for the pastoralist context is an integral approach to ensure that pastoralist households send their school-age children back to the learning spaces/schools.