This blog was written by Pauline Rose, Director of the Research for Equitable Access and Learning (REAL) Centre at the University of Cambridge, with support from Tom Kirk, Communications Manager, and Sandra Baxter, Research Associate, at the Faculty of Education, University of Cambridge.

A new report is urging for adolescent women to be given more of a priority within international efforts to end poverty and achieve other development targets by 2030. It argues that there is an urgent need to do more to support marginalised, adolescent women in low- and middle-income countries, many of whom leave education early and then face an ongoing struggle to build secure livelihoods.

The report ‘School to Work Transition for Adolescent Girls’ is published today, alongside a Summary Report, on 11th February, International Day of Women and Girls in Science, by the Research for Equitable Access and Learning (REAL) Centre at the University of Cambridge, and commissioned by the UK’s Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO).

According to UNESCO data, only around 30 per cent of all female students select STEM-related fields in higher education. Globally, female students’ enrolment is particularly low in ICT (3%), natural science, mathematics and statistics (5%) and in engineering, manufacturing and construction (8%). Yet there is extensive evidence highlighting the difficulties adolescent women face, and estimating that almost a third in low- and middle-income countries are not even in education, training or work. For many, a quality education remains a far-off dream. In sub-Saharan Africa, for example, fewer than one in ten girls from poor households in rural areas complete lower secondary education.

‘Adolescents’ (technically people aged 10 to 19) comprise about one sixth of the world’s population. Women in this age group are some of the most vulnerable people in the world, and the report argues that supporting them should be a cornerstone of international efforts to end poverty. Unless this happens, it warns it is unlikely that the UN’s 2030 Sustainable Development Goals – including ending poverty, ensuring inclusive education, and empowering women and girls – will be met.

In particular, the research highlights the need for more concerted efforts to be made to prevent gender discrimination in labour markets, strengthen social safety nets for women, and provide both formal education and continued training for the huge numbers of adolescent women who, it says, ‘have missed out on acquiring relevant skills to enhance their livelihood opportunities.’

Marginalised adolescent girls, who experience extreme poverty, live in rural areas, have disabilities, are affected by conflict, or belong to disadvantaged groups need to be prioritised both in education and as they transition into work. Millions are being left behind by a range of interlocking problems, and strong, sustained political leadership is needed to turn that around. This is discussed in more detail in a previous report, also commissioned by FCDO: ‘Transformative political leadership to promote 12 years of quality education for all girls’.

The Government has identified girls’ education as a key focus of the UK’s presidency of the G7 group of industrial countries this year, and gender equality will be mainstreamed across the different ministerial tracks. The new report raises gender inequality – both in education and employment – as major areas of concern for the international community.

The report further stresses that adolescence is a make-or-break time for many girls in low- and lower-middle-income countries and should therefore also be a focal point of international efforts. During this period, many young women leave education early, either to work, or because they are expected to marry and start a family. Often, they do so without having acquired basic literacy or numeracy. In addition, very few have the transferable skills or training that they need to succeed in the world of work.

Many also struggle to find secure employment. Data from 30 low- and middle-income countries suggests that 31% of young women are not in education, employment or training, compared with 16% of boys. Those who do find jobs, frequently work for low wages, in unsafe settings and without any sort of social safety net.

One of the main reasons for this is a lack of access to appropriate skills development and training opportunities. For example, one in three unemployed adolescent girls in the Asia-Pacific region, and one in five in sub-Saharan Africa, report that the entry requirements for their preferred career path exceed their education and training.

Compounding these problems, gender discrimination in both labour markets and wider society is an accepted norm in many countries. Among many other examples, this manifests itself in inheritance laws which transfer land and property to sons but not daughters; the tendency to force girls who struggle to find work into early marriage and childbearing; and widespread gender-related violence. One study in Nigeria, cited in the report, found that two thirds of young female apprentices had experienced physical violence – and 39% said that their employer was the most recent perpetrator.

While the research also identifies many successful individual programmes around the world that address some of these issues, it stresses the need for policymakers internationally to prioritise adolescent girls in larger-scale, systemic reforms.

It also makes numerous recommendations about how that can be done, including:

- Implementing measures and laws that challenge gender discrimination in education, labour markets and wider society.

- Curriculum reforms to develop women’s transferrable skills in school, supported by skills development programmes outside the education system.

- Catch-up programmes for those who have missed out on a basic education.

- Strengthening social safety nets, which has been shown to benefit women in particular.

- Providing sexual and reproductive health services and information for all adolescent girls.

- Providing counselling and rehabilitation services that offer practical support to adolescent girls who have been forced into unsafe work settings.

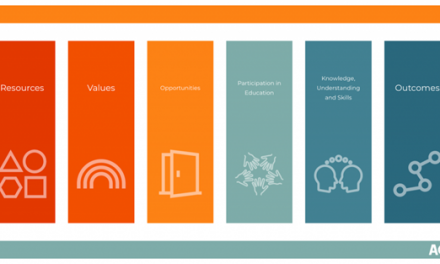

Addressing barriers to girls’ access to livelihoods requires long-term structural change at the systems level and changes to social norms. In the light of the reforms that are needed, the report makes recommendations for both political leaders and policymakers. The full set of recommendations for policymakers is summarised here in Figure 1.

The report highlights the particular role that female political leaders and parliamentarians can play in driving forward a more integrated agenda for marginalised young women, and in challenging patriarchal norms that hold back gender equality.

It also warns that many of the trends documented are currently at risk of becoming worse as a result of COVID-19. The best way that governments can signal their commitment to this problem is by putting women and girls at the forefront of COVID-19 recovery efforts and ambitions to build back better.