UKFIET is one of the leading global conferences on international education and development. The theme of the conference this year was inclusive education systems. In this blog, Dr Stephen Thompson, Post-Doctoral Research Fellow at the Institute of Development Studies (IDS), explores the potential for participatory approaches to strengthen disability inclusive education. For the 2019 UKFIET conference, 17 individuals, including Stephen, were provided with bursaries to assist them to participate and present at the conference. The researchers were asked to write a short piece about their research or experience.

Over the last three decades, the UKFIET conference has gained a reputation for asking the challenging questions with regards to international education and development. It was clear that the 2019 gathering would be no different as it was announced that the focus would be on inclusive education systems. It has been 25 years since the UNESCO Salamanca Statement endorsed the idea of inclusive education, yet progress towards its realisation has been frustratingly slow. Despite various frameworks (including the Convention of the Rights of People with Disabilities and the Sustainable Development Goals) reaffirming the right to inclusive and equitable education for all, practical application remains limited.

I organised a workshop, along with my colleagues Brigitte Rohwerder and Mary Wickenden from the Institute of Development Studies (IDS), on how participatory approaches could be used to include the voices of children with disabilities and contribute to improving inclusive education in primary schools.

I organised a workshop, along with my colleagues Brigitte Rohwerder and Mary Wickenden from the Institute of Development Studies (IDS), on how participatory approaches could be used to include the voices of children with disabilities and contribute to improving inclusive education in primary schools.

Although the focus of the conference was inclusive education systems in its broadest sense, our workshop focused specifically on disability inclusive education. Of course, other factors can result in exclusion from education (something I explore in more detail in this recently published working aid), and this is always unacceptable. However, marginalisation due to disability is a particularly significant challenge, so this is why we chose to focus on it.

Using participatory approaches to ensure that the voices of children with disabilities are included

We began our session by describing our plan to use participatory approaches in work we are doing on inclusive education in Nigeria, in collaboration with Sightsavers and other members of the Disability Inclusive Development (DID) programme. Our discussions were centred around the potential to hear children’s perspectives in order to develop child-centred solutions to inclusive education systems. We were delighted that, of the 20 workshop participants, half were from sub-Saharan Africa and a quarter were from Nigeria. Their participation brought an authenticity to the session, allowing the conversations to be grounded in lived experience.

with Sightsavers and other members of the Disability Inclusive Development (DID) programme. Our discussions were centred around the potential to hear children’s perspectives in order to develop child-centred solutions to inclusive education systems. We were delighted that, of the 20 workshop participants, half were from sub-Saharan Africa and a quarter were from Nigeria. Their participation brought an authenticity to the session, allowing the conversations to be grounded in lived experience.

We were also pleased to hear that many participants agreed that including the voices of children with disabilities in the research was vital and it was entirely logical to do this.

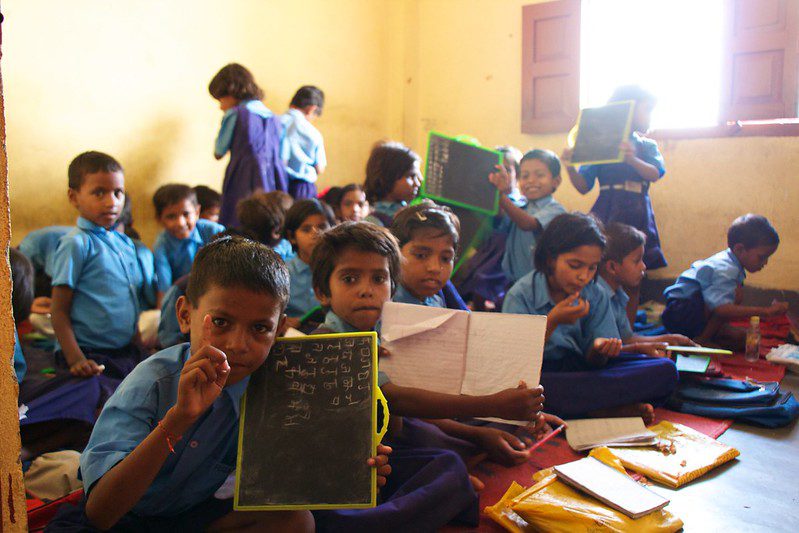

Yet so often it does not happen. The trend of consulting children themselves is rarely extended to children with disabilities. This paper by Wickenden and Kembhavi-Tam argues that such children are often accidentally forgotten, assumed to have nothing to say or perceived to be methodologically difficult to include. With necessary adaptations, accommodations and careful thought, it should be possible to engage all children in research about decisions and processes that impact on them. There were also some reflections on managing the expectations of children (and parents) involved in research. Education systems are complex and change can be slow to achieve. This should be made clear from the earliest engagement.

Workshop participants were keen to know if any resources existed that give practical guidance for undertaking inclusive research with children with disability. The best resource I know of to cover this topic was written by Elena Jenkin and colleagues from Deakin University. It describes several tools that can be used to include children with disabilities in research and offers support to guide researchers how to use them.

Creative approaches can help children map barriers and enabling factors to accessing education

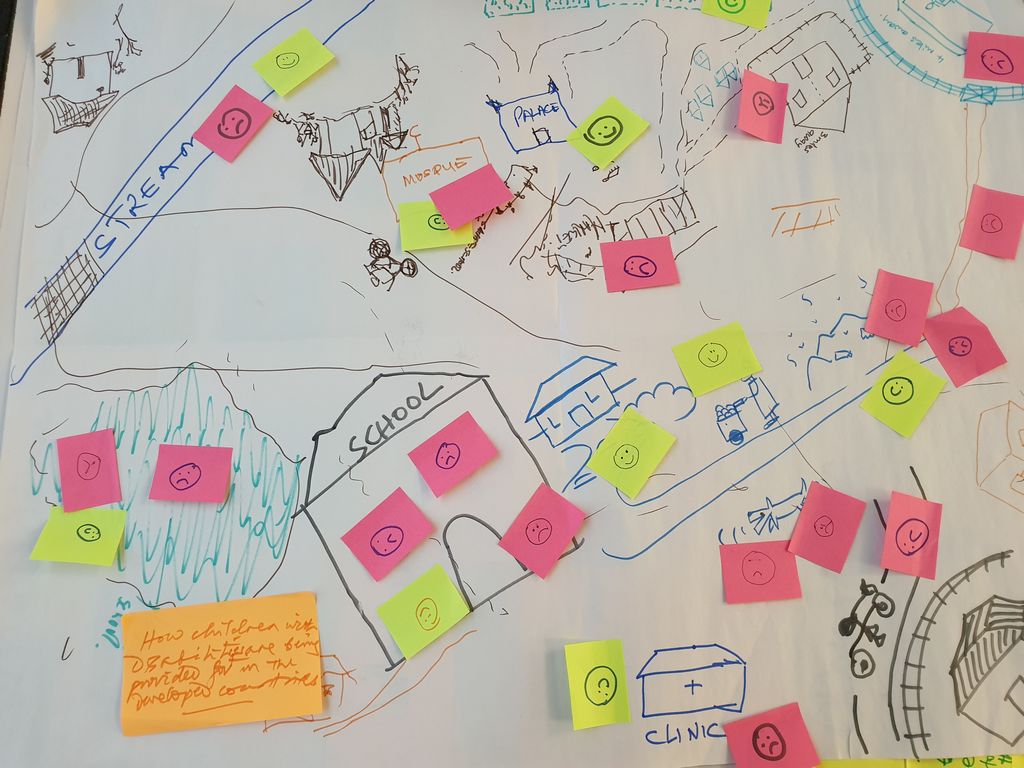

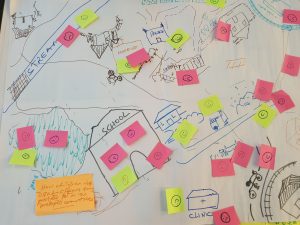

One of the approaches we presented was a mapping exercise where children with disabilities are invited to draw their village and comment on what might be a barrier or an enabling factor to them accessing school. The exercise is designed to gain an understanding of how the children feel, through a fun, creative and inclusive participatory process.

One of the approaches we presented was a mapping exercise where children with disabilities are invited to draw their village and comment on what might be a barrier or an enabling factor to them accessing school. The exercise is designed to gain an understanding of how the children feel, through a fun, creative and inclusive participatory process.

There was some concern amongst workshop participants as to whether children would engage with the activity – would they be comfortable to draw? In my experience, children jump at any opportunity to draw, and if their impairment makes this difficult, adaptations to the methods can ensure that everyone can join in and contribute. Such unchecked creativity seems to disappear with age. We unlearn how to be creative the older we get.

Our discussions foreshadowed one of the central themes of the conference keynote speech delivered by Andria Zafirakou, who won the Global Teacher Prize in 2018. She urged for creativity to be recognised as a vital part of education and argued for it not to be restricted to just the Arts. Her call to celebrate creative process in education will hopefully have reassured our workshop participants that, given the chance and with careful consideration about each child’s needs, children would relish the opportunity to be involved in a creative participatory activity to better understand their exclusion from education systems.

Education is about more than creating a pathway to employment

It was raised that parents of children with disabilities may be unenthusiastic about education for them in the context of high unemployment, which peaked at an all-time high of 23 percent in Nigeria last year.

Why bother fighting to get their children educated if it won’t make a difference to their future anyway?

This concern is real and justified. However, it must be recognised that going to school is about more than just a pathway to employment. Friends are made and social as well as academic skills are learnt along the way. If children with disabilities are excluded from schools, they may also end up being excluded from society. Also, improving the education system may go some way to improving employment (although it is recognised that other factors must also improve).

The importance of improving the capacity of teachers to teach inclusively

Improving access to school without considering quality of learning in the classroom is only solving half the problem. Teacher capacity is central to the learning process. Research from elsewhere in Africa has shown that a vibrant in-service and pre-service teacher training programme to improve inclusive practices must be developed by the Ministry of Education, alongside the development of an inclusive curriculum, if the diverse educational needs of all learners in mainstream schools are to be catered for. Part of the DID programme in Nigeria will involve working with teacher training colleges to improve inclusive teaching. We hope to present some of our learnings of this endeavour at UKFIET conferences in years to come.

A final reflection

The whole conference gave an excellent opportunity to reflect on the past, present and future of inclusive education systems broadly and disability inclusion issues more specifically, and it was an honour to be part of those discussions. We hope our workshop offered a glimpse of the potential participatory approaches can have in ensuring no one is left behind in education. The most important take away message from our workshop was that if we are to make progress over the next thirty years towards inclusive education, we must involve children themselves in the journey.

The whole conference gave an excellent opportunity to reflect on the past, present and future of inclusive education systems broadly and disability inclusion issues more specifically, and it was an honour to be part of those discussions. We hope our workshop offered a glimpse of the potential participatory approaches can have in ensuring no one is left behind in education. The most important take away message from our workshop was that if we are to make progress over the next thirty years towards inclusive education, we must involve children themselves in the journey.