The UKFIET 2019 conference had 6 themes relating to Inclusive Education Systems. Patrick Montjouridès, a PhD candidate with the Faculty of Education at the University of Cambridge, was a convenor for the theme ‘Education technology and data science for inclusive systems’.

‘Education technology and data science for inclusive systems’ – the title set the tone for this theme. The starting point for the discussion has been set to transcend the former focus on ‘ICT’ as a lone-standing topic. Instead, the theme focussed the attention on technology in the context of its instrumental and system-wide use. Furthermore, the theme responded to the interlinkage of technology and data, an increasingly inseparable couple. So how does the education community perform against increasing technological opportunities and high data intensity, two of the main features that characterise our time?

More than 40 panelists, discussants and quickfire talkers from the field of academia, practice, international organisations, as well as donors in international development cooperation, contributed to the theme and provide valuable insights in response to this question. A total of nine thematically-arranged panel sessions addressed a wide range of topics from the complex interaction between teachers and technology, to using technology as a tool to identify and support the most vulnerable, to the immediate, as well as more distant, implications of an ever-increasing use of data and technology.

The variety of aspects addressed under this theme thereby highlights that Education Technology and Data Science may no longer be considered ‘topics’ in education, but instead, they increasingly pervade evolving norms and standard practices in the sector. Notwithstanding the rich diversity in contributions, over-arching insights emerged from the sessions that allow an initial reflection on the question of where the education community stands with respect to ‘Education Technology and Data Science’. Having had the honour to co-convene this panel together with Kate Radford, then at WarChild Holland, I will share five main reflections that, I think, emerged from the discussions:

- Power and Creativity of the Community

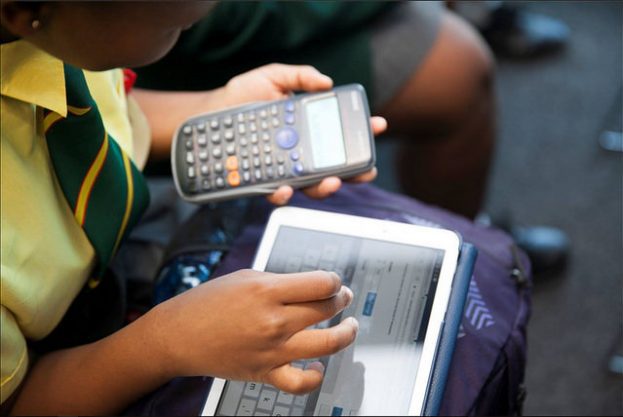

Firstly, this year’s contributions underscore the innovative power and creativity of the community to develop contextualised EdTech solutions. More than a dozen education apps and software programmes were presented and discussed, from the Tangerine tutoring software for teachers, and curriculum-based digital games of the Can’t Wait to Learn programme, to Jolly Futures’ interactive lesson plans. The panelists also provided inspiring examples of contextualised solutions that are grounded in a reflection on the adequacy of the technological means. Examples were showcased where researchers replaced an electronic interactive interface with a visually and functionally equivalent paper version accompanied by assessments mechanisms that mimicked the app behaviour (using daily life objects found in the household, for instance). ‘Thinking back’ (that is, in terms of technological complexity) may then be ‘thinking forward’ when it comes to providing contextualised and sustainable solutions – particularly when reaching out to the most marginalised as a guiding principle of the community’s shared agenda.

Another inspiring example, where the context-sensitivity of EdTech solutions was put at the centre, was shared at the conference. This example addressed the digitalisation of an Education Management Information System (EMIS) whereby the technological implementation was designed to mirror the functioning of the preceding and effective paper-based implementation. By building on existing habits, rather than disrupting them, the way was paved for a smooth transition towards a fully-digitalised data collection, with all its additional advantages. This approach has the potential to successfully reduce entry barriers and foster motivation of the actors involved. Despite these context-sensitive innovations, implementation remains a challenge in the field, which leads me to my second point.

- Actively learning from and reflecting on challenges

There is a popular formula in innovation business which stresses that success is 5% idea, and 95% implementation. Presentations illustrated how the community has learned from and actively engages in the reflection of implementation challenges, as well as how these can be overcome. For instance, there was an engaging discussion about an innovative instructional plasma TV programme in Ethiopia, which neglected the need to appropriately integrate specific training for teachers to interact, both physically and pedagogically, with the new pedagogical support. Not only did the instructional programme require teachers to understand how to use the various features of the programme, but it also required for teachers to account for a second and sometimes contradicting source of authority in the classroom.

Research showed that neglecting the need for building the necessary competencies with respect to the use of technology, as well as in terms of the interaction with it, can result in teachers’ dismissal of the new pedagogical support. A point also highlighted by Nafisa Baboo, Senior Director on inclusive education for Light of the World. As part of her keynote speech at the opening plenary, Nafisa Baboo stressed the importance of putting competencies of anticipated users at the centre whenever new technology is introduced. Thus, whereas the implementation challenge continues, the rigorous analysis of, and conscious reflection on the 95% implementation side and its embedded failure and success factors, forms a precious asset of a learning community.

- Diverse EdTech offer met by expanding demand

Thirdly, the diverse EdTech offer is met by a solid and rapidly expanding demand side, with donors – not least to mention philanthropic organisations – showing a strong interest in, and readiness to implement EdTech-based interventions. But how to navigate in the vibrant ‘market’ of EdTech innovation and data science? A lot of uncertainties remain with regards to successes, best practices, scalability and cost-effectiveness.

Perhaps due to the nature of the field which brings together stakeholders with different perspectives, namely tech companies, apps and software developers, academia, and education practitioners, the education community has been struggling to gather conclusive evidence and to fill in the knowledge gaps. DFID presented its EdTech Hub to address such knowledge gaps and to facilitate an evidence-based navigation in this young and dynamic field, and notably ensure that the education community goes beyond information and validation provided to date mostly by vendors. As donors reach out to join hands with the research community, the question, where the education research community stands, merits further attention.

- Skills need to evolve with the evolving education landscape

This leads me to the fourth point I want to highlight – and which leads me back to the title of the theme: Education Technology AND Data Science. Yet, so far, in much of the above discussion, I made more explicit reference to the former of the two notions. So, what about Data Science? And it is exactly here, where the education research community has another central role to play: the education landscape is evolving and so should the skills of the researcher, in order to remain attuned to, and able to grapple with its object of inquiry.

This leads me to the fourth point I want to highlight – and which leads me back to the title of the theme: Education Technology AND Data Science. Yet, so far, in much of the above discussion, I made more explicit reference to the former of the two notions. So, what about Data Science? And it is exactly here, where the education research community has another central role to play: the education landscape is evolving and so should the skills of the researcher, in order to remain attuned to, and able to grapple with its object of inquiry.

Innovative presentations on using machine learning to detect, and to develop targeted interventions to prevent children from dropping out, point to the inspiring potential associated with the integral use of data science in education research. Another example demonstrated that leveraging thousands of research articles using bibliometric methods has the potential to improve the exhaustivity, interpretability and conclusiveness of text-based analysis – qualities that methodologies conventionally employed in systematic literature reviews keep struggling with. These presentations hinted at the vast room for innovative manoeuvre, once the education research benefits from the thorough integration of computational methods in the collection, analysis, and visualisation of the wealth of data that is being generated every day and in the context of new EdTech applications.

Engaging further in this direction would foster trusted assessments of EdTech interventions, and also steer the field of education towards a more cumulative science. As education technology has the potential to become a viable and sought-for option to resolve the learning crisis, cross-fertilisation between academia and practitioners is needed more than ever, to ensure that successes are known and validated, and that failures are not replicated – and data science capacities are pivotal to unlock this development.

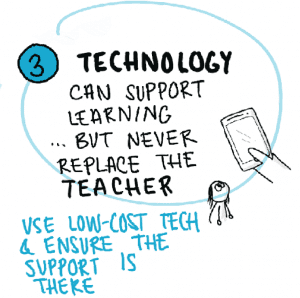

- Technology alone cannot lead learning

The fifth and final point is what I felt was a word of caution sent by several presenters: social, conceptual, philosophical and ethical thinking in education should not stop at the door of technological endeavors. The aforementioned instructional plasma TV example, stands in for several examples which highlighted that education is, above all, an area of research and practice that takes place in the social world. And education interventions and research can consciously or unconsciously be influenced by the work of the researcher and practitioner.

Several references related to this, such as in the opening plenary, in which Nafisa Baboo highlighted that “technology can be a tool for learning but cannot replace a teacher and does not allow children to socialise and experience the real world”. Similarly, there was a number of discussions about how tools, but also data analyses can, despite the best intentions, contribute to marginalising and stigmatising children, either by reinforcing their self-perception as not belonging to a “norm”, or by conveying misleading narratives that can lead policy-makers and other researchers to continue opposing diversity and normality. We need to apply caution with regard to the analysis and presentation of results which are the last mile of a comprehensive approach to validate and disseminate results of an innovative intervention.

Several references related to this, such as in the opening plenary, in which Nafisa Baboo highlighted that “technology can be a tool for learning but cannot replace a teacher and does not allow children to socialise and experience the real world”. Similarly, there was a number of discussions about how tools, but also data analyses can, despite the best intentions, contribute to marginalising and stigmatising children, either by reinforcing their self-perception as not belonging to a “norm”, or by conveying misleading narratives that can lead policy-makers and other researchers to continue opposing diversity and normality. We need to apply caution with regard to the analysis and presentation of results which are the last mile of a comprehensive approach to validate and disseminate results of an innovative intervention.

Furthermore, it was pointed out that even global institutions need to remain careful as they seek to develop assessments of global competences for inclusive education systems. Badly formulated items can, for instance, contribute to spreading stigmatising stereotypes, and the pursuit of a universal learning progression (and therefore benchmark) might not be as inclusive as the name implies, should measurement not enable to account for the multiplicity and diversity of contexts in which it is carried out.

The 2019 UKFIET conference provided us with insightful presentations on the role of Education Technology and Data Science in the pursuit of inclusive education systems. While relatively new terms, their notions may be considered as the next iteration of ICTs and statistics with new features, new challenges, but also carrying forward old and unresolved issues and critics. If anything, this showed that inclusive education systems can hinge on better use of technology and data science, but this perhaps implies, more than ever, the realisation of education as a truly multidisciplinary or even interdisciplinary field of study.