By Dr Alison Buckler, The Open University, UK; Dr Faith Mkwananzi, The University of the Free State, South Africa; Dr Liz Chamberlain, The Open University, UK; and Ms Caroline Dean, Plan International, UK. These issues were discussed during a session at the September 2019 UKFIET conference on inclusive education systems.

Earlier this year we launched a research collaboration between Plan and The Open University. The research – a component of the SAGE (Supporting Adolescent Girls’ Education) programme, funded by DFID’s Girls’ Education Challenge – is mapping the aspirations of out-of-school girls in Zimbabwe as they participate in a community-education initiative.

The first activity was a residential storytelling research workshop in Harare. One day we were walking to lunch with a participant called Tatenda. We asked her how she was getting on. She said she felt like a hare walking through a field of grass. As she passed through the hotel, meals appeared, beds were made, floors were swept – she could focus on the workshop without thinking about anything else. She said that the grass closed behind her, leaving no trace, that no one had ever looked after her like this before.

Tatenda is 19 and from Manicaland Province. She has a visual impairment, congenital limb-difference and an undiagnosed developmental disorder. She is the main breadwinner for – and full-time carer of – her husband and their daughter, who also have multiple disabilities. Tatenda does manual labour seven days a week and is setting up a poultry enterprise.

If we had travelled to Tatenda’s home to interview her about her aspirations, we would have been lucky to get five minutes of her time, let alone five days.

***

The starting point for the paper we presented at the 2019 UKFIET conference was the need for more open and honest debates around possibilities for and limitations of researching with ‘excluded’ groups. We argued for more critical reflection within the international education community on whether the ways of knowing we draw on are as inclusive as the education systems we intend to develop.

People may be thinking about this, but few are writing about it. We analysed 100 articles in international education journals published since 2000. We focused on key words like inclusion/inclusive, exclusion/excluded, diversity/difference and in/equality. While there was a recognition that large-scale surveys can miss (important) people out, and a fairly consistent nod to conscious sampling, only ten articles reflected on the inclusiveness of the methodology and only three articulated how they had specifically developed the methodology around their conceptual understanding of inclusion.

So, while inclusion is increasingly researched, academics who write, edit and peer-review articles are not putting pressure on each other to consider the extent to which approaches for researching inclusion are, in themselves, inclusive. They are not publicly questioning if these approaches might perpetuate normative conditions in particular contexts that render people excluded in the first place, and potentially exclude the most excluded from the data.

***

So, what do we mean by ‘inclusive ways of knowing’? It’s a framework we’re developing to help us design better quality international education studies. It is definitely bigger than sampling: we think it requires big-sky thinking around the paradigms the research is rooted in (for us these are socio-cultural learning, social justice, post-colonial critiques, and social models of disability) and how researchers practically apply these paradigms to the personal, strategic and logistic decisions they make when planning and carrying out research. It involves – among other things – critical and honest reflection on who is doing the research, for what purpose, and how. It focuses on participants, but also on place and power. It includes – but sometimes challenges – conventional ethics guidelines. It questions who owns and has access to data, and who is credited for research outputs.

We have been reflecting on our research with out-of-school girls in Zimbabwe through the ‘inclusive ways of knowing’ framework. The research uses the ‘transformative storytelling’ approach developed by Joanna Wheeler[1]. Transformative storytelling supports participants to construct and reconstruct a narrative around a particular moment in their life. We adapted the approach to welcome and engage girls with a diversity of ages, cultures, religions, access-preferences, dis/abilities, family obligations, levels of education and language.

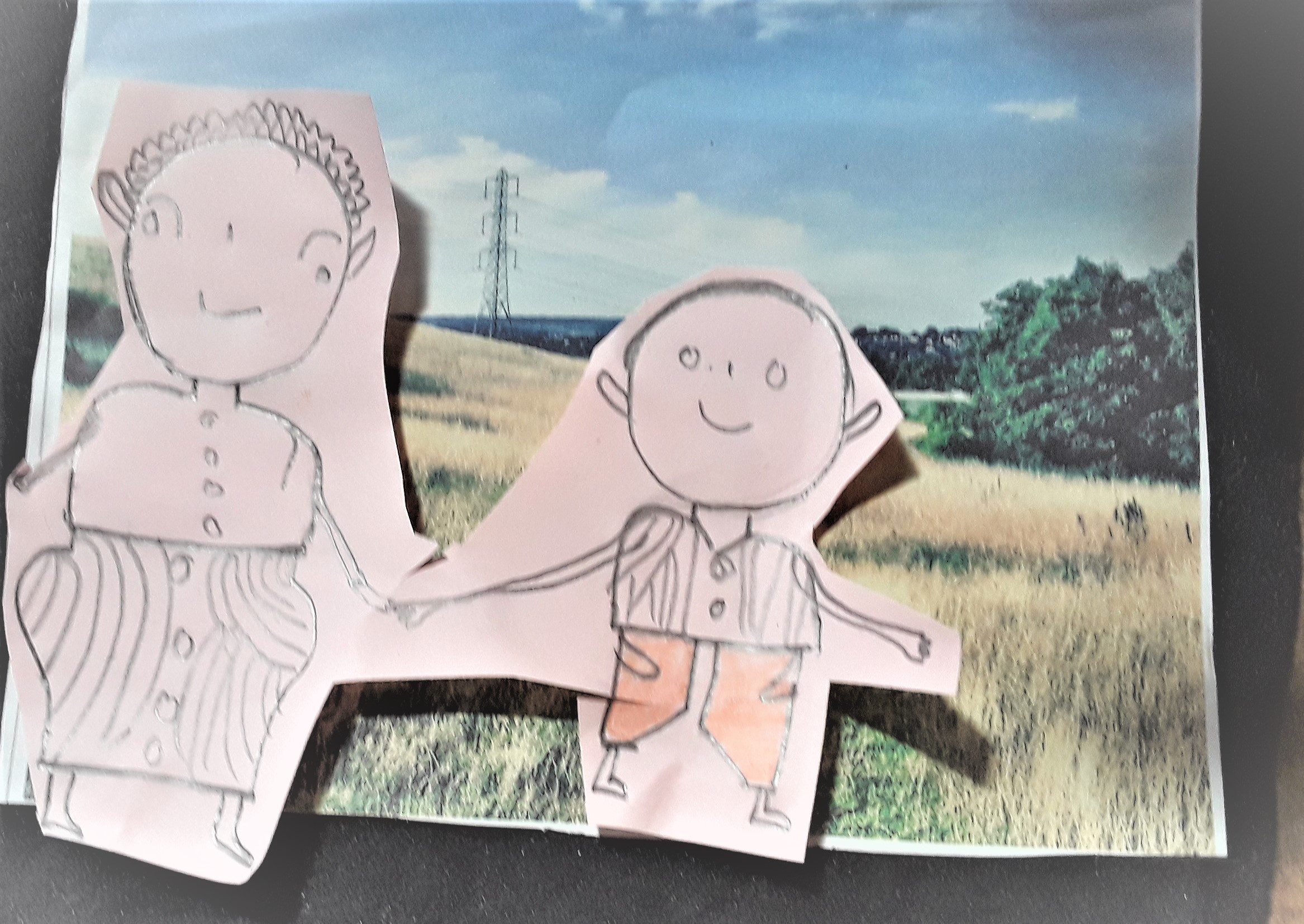

We developed a 5-day residential storytelling workshop in Harare. Through a range of extremely carefully curated activities including collage, drawing, clay-modelling, drama, dance and a lot of listening, each girl was supported to create a digital story about a point in her life when her aspirations changed. The workshop was carried out in three languages and was entirely text-free.

Through an analysis of the research using the inclusive ways of knowing framework we can articulate who we were able to include and engage and how. But we can also identify the limitations of the research: younger girls and girls with more severe disabilities, for example, were outside our capacities to include ethically and safely without additional resources or skilled-personnel. Time-factors meant that we were unable to include the girls in the first-stage-analysis to the extent we had hoped. We are conscious of the implications of having a UK-based research-lead (although four of the five co-researchers are Zimbabwean).

We also acknowledge that – because of her undiagnosed condition – Tatenda slipped through the net into our list of participants. Without meeting her we would have been uncertain of our ability to make the experience positive for her. Yet her story, insight, creativity and confidence added so much to the research (including a glimpse into the challenge for rural children to get a medical diagnosis and appropriate support).

So, we are aware that this research does not represent a fully inclusive process: we question if any piece of research ever could. But we argue that recognising, reflecting on and reporting where and how research processes do exclude certain people and their perspectives is a crucial step for enhancing knowledge around inclusion.

[1] Wheeler, J., Shahrokh, T. and Derakshani, N. (2019) Transformative Storywork: Creative Pathways for Social Change, in J. Servaes (Ed) Handbook of Communication for Development and Social Change, Springer: Singapore.