This blog written by Tal Rafaeli was originally posted on the Education Development Trust website on 5 September 2018.

School inspection: for too many schools in Sub-Saharan Africa inspections call to mind a burdensome box-ticking exercise. But, done well, school inspection is an art which has the potential to transform teaching and learning. The question is – what does it take to do inspections well in a low-income context, where inspection systems face the challenge of having very limited resources to drive the entire education system forward?

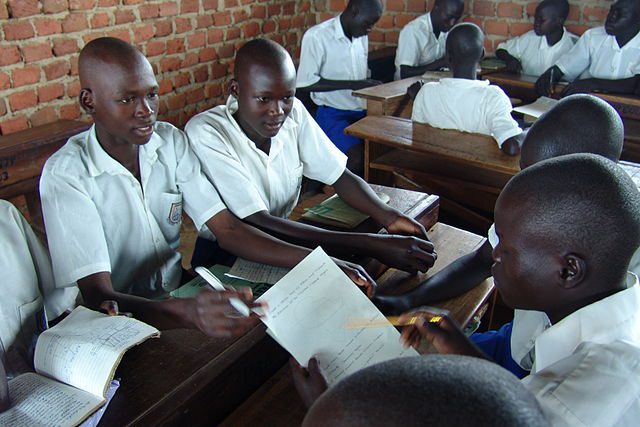

One of the biggest challenges that the education world is facing is that improving access to education does not necessarily lead to improved learning outcomes. To illustrate, less than 50 per cent of grade 6 students in Southern and East Africa are able to read beyond basic word identification (WDR, 2018). There is an urgent need for education systems to understand both whether teaching and learning is taking place and why is it succeeding or failing in improving learning outcomes. As one of the best ways to do so is inspections systems, they have become a strategic priority for education ministries in low-income countries. But they can often be expensive and complex to run, as Education Development Trust knows from 20 years of experience supporting inspections reform in England, the Middle East and in South-East Asia. As part of Ghana’s ambitious education reform agenda, I have recently had the privilege to partner with the National Inspectorate Board (NIB) in Ghana, supporting them to translate the best available international inspections expertise to develop and pilot a ‘lean’ inspection model for a low-income context. So how did we go about it?

Understanding the context

When it comes to inspections, there is no ‘one size fits all’. As emphasised in Education Development Trust’s research into effective external school review, for inspections to be effective they need to match the local context (Churches and McBride, 2013). The art of inspections is in learning and understanding the unique structure, behaviours, strengths and weaknesses of an education system and finding the best practice that is relevant for it. Without this contextualisation, we risk creating negative impact, such as demoralising school leaders (Global Education Monitoring Report, 2017/8). With this in mind, it was clear that the first step in developing the ‘lean’ inspection model was gaining a deep understanding of the Ghanaian education system.

At the heart of this contextualisation process was establishing a strong partnership with NIB and its team of inspectors, setting out to together develop a ‘lean’ inspection model for Ghana. We started with a 10-day co-design visit. What felt exceptionally important during this visit was conducting school visits with the NIB inspectors. As a great part of inspections is the art of relationships and communication, there was no better way to understand the Ghanaian inspection system and its inspectors than to see them in action. This enabled us to understand the behaviours and mindsets of the NIB inspectors and, together with them, reflect which ones serve effective inspections – which help all stakeholders identify the causes of student learning or underperformance – and which behaviours and mindsets present a barrier. In addition, it enabled the Education Development Trust inspectors to model fresh approaches to inspections from day one. This collaboration, modelling and reflection supported the professional development journey of the NIB inspectors and created a true sense of shared ownership.

A focused approach

The NIB’s vision was clear: to build a low cost but not low skilled inspection model. We helped NIB achieve this in two ways. Firstly, we designed an inspection framework which focused on the key priorities of the Ministry of Education and the main drivers of school improvement:

- teaching of English and mathematics

- learning of English and mathematics

- school leadership.

This focused approach reduces the time required for inspections – and so lowers their cost – but still provides valuable diagnostic information to the ministry and the individual school.

Achieving sustainable impact

Secondly, we considered how to achieve sustainable impact from the inspection process: we needed to make sure that beyond rich diagnostic data, the school inspection process will actually lead to change and improved teaching. To do so, an inspection framework needs to act both as a standards setting and a development tool for schools as they begin to consider ‘what does good look like?’ and ‘what do I need to do to improve?’. To support this, we developed clear quality indicators, illustrated by observable activities and behaviours to explain what unsatisfactory, satisfactory, good or excellent performance look like in practice.

These two approaches – focused inspections and breaking down standards to observable behaviours – were at the heart of the inspection framework that we developed and trained the NIB inspectors to use. To continue the modelling approach, our team of inspection experts modelled the inspection outlined in the framework in a live inspection which all trained inspectors took part in. With these tools at hand, the team of inspectors carried out 20 pilot inspections which ended in early July.

Developing a culture of school improvement

It is still too early to tell the extent of the impact of the pilot of the ‘lean’ inspection model, but the reaction so far has been impressive. Not only has the pilot, and the professional development, been strongly welcomed by the NIB inspectors, it has also been welcomed by the wider system. For example, the Executive Secretary of National Council for Curriculum and Assessment (NCCA) has shown interest for this inspection framework to inform the Council’s important work setting the new teaching and learning standards in Ghana. Though there is still much work to be done towards perfecting this ‘lean’ inspection model, we are confident that this process has set the foundation to continue to develop and scale a culture of school improvement across the education system in Ghana.

A vital component of enhanced leadership in low income economies is providing enhanced and rich educational dialogue between school leaders. At AKES we are following the introduction of school standatds with this kind of enhancenent and the article about work in Ghana is thoughtful and commensurate with our own findings.

Peter Davies Standards for Schools

Aga Khan Education Service

http://www.wgphdavies.com