As political leaders and civil society gather at the Oslo Education and Development Summit, people with disabilities, advocates, and researchers will be watching closely. How will leaders at the Summit take forward promises made at the World Education Forum in Incheon, South Korea in May, notably to focus ‘efforts on the most disadvantaged, especially those with disabilities, to ensure that no one is left behind’?

As political leaders and civil society gather at the Oslo Education and Development Summit, people with disabilities, advocates, and researchers will be watching closely. How will leaders at the Summit take forward promises made at the World Education Forum in Incheon, South Korea in May, notably to focus ‘efforts on the most disadvantaged, especially those with disabilities, to ensure that no one is left behind’?

The Norwegian government’s commitment to addressing disability at the Summit is clear. This is evident from their commissioning of a background report which brought together a group of disability experts from the donor community, advocates and researchers of which I was privileged to be part.

Given stated commitments to ensuring all children, regardless of whether they have a disability, have access to a quality education, there is now an urgent need to set in motion mechanisms and processes that will provide concrete steps for action. This call arises from a commitment towards disability underpinned by a focus on rights as laid out in the 2006 United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. To translate this vision into reality, a robust evidence-base is needed to identify effective ways of addressing the challenges faced by education systems, and accompanied by investment of resources.

The global investment in people with disabilities has so far been dismal. While exact figures on funding allocations are unavailable, there is significant variation in the extent to which disability is recognised in education plans across countries. In Pakistan the National Policy of Action recognises the needs of people with disabilities but lack of implementation remains a major problem. The World Bank currently has eight projects on education and none of these explicitly include children with disabilities.

By contrast, India has one of the most enabling disability policies and a clear focus on children with disabilities under its on-going education flagship programme, the Sarv Shiksha Abhiyan (SSA). Nonetheless, the investments in disability have been very low. The National Centre for Promotion of Employment for Disabled People reported that the country was spending only 0.0009 percent of its GDP on disability. This included allocation for programmes across key ministries such as health, education, labour, rural development, youth affairs and sports.

A decline in investment is apparent at the state level in India. For example, between 2011-12 and 2013-14, the amount spent on a child with disabilities more than halved in the southern state of Karnataka. On the one hand it could be argued that the non-recurring nature of a number of activities in 2013-14 such as building of ramps, or new resource centres at the district level, justifies this decrease, on the other, better rates of identification of children with disabilities, and hence a likely increase in the number of children enrolling under various programmes, are not accounted for.

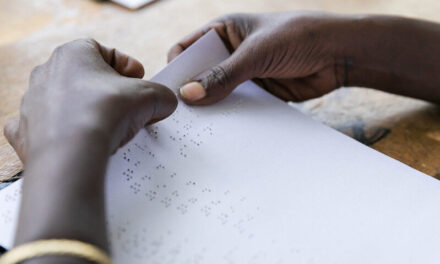

Greater accessibility to schools with the building of ramps and toilet is an important step forward. However, this is just the starting point. There is, for example, a need to invest in accessibility to the curriculum for children with different types of impairment. Assistive devices, such as braille, hearing aids etc, are also required. More fundamentally, there is a need to invest in teachers and other resource personnel so they can respond effectively to the needs of children with disabilities. Teacher education needs to prepare teachers for diversity in the classroom. Training requires a consistent and long term commitment, which entails re-shaping fundamental assumptions about learners, as well as equipping teachers with a range of pedagogical skills to respond to diverse needs.

All this requires financial investments. These investments will have multiple benefits, not just by producing high quality teachers whose holistic teaching styles will be of benefit to all children, but also recent evidence reminds us that returns to investment in education for persons with disability are two or three times higher than that of a person without disability.

In parallel, we need to continue to think of better and more effective ways of investing in education systems which will truly promote learning for all, including those with disabilities. To date, very little research on disability and education emerging from developing economies has added powerful insights into how to better include children with disabilities. Research studies have so far helped to provide an understanding of parental, societal, or teacher attitudes towards disability.

However, the biggest lacuna in current research is the absence of ‘how’ to make the promise of education a reality for children with disabilities. While international policy mandates continue to aspire for “inclusive education” there is little awareness of how this is best achieved in practice in different socio-cultural and educational settings. There are growing calls for developing culturally and contextually situated models which allow for greater engagement amongst diverse stakeholders. So what should future research engagement look like?

We need….

…Research which illuminates how changes in policy and wider society are impacting the educational landscape for children and young people with disabilities. This should involve and engage children/young/adults with disabilities to better understand their lived experiences and the impact of schooling on their current and future life opportunities, both for them and their families.

…Develop reliable measures for identifying children with disabilities in current school populations and out of school groupings, in order to make effective policy recommendations in terms of planning resources and personnel.

…Closer investigation of classroom pedagogical practices to understand how teachers teach all children and in particular those with disabilities. Such empirical insights will enable us to make strong recommendations for changes in teaching and learning practices in developing economies which are faced with a particular set of challenges and opportunities.

…Research to be truly participatory and ethical. We need research which works with persons with disabilities, but we also need researchers to form enabling cross-national alliances, which respect diversity of knowledge. It is only when are open to new forms of working can we can seek innovative solutions to long held concerns.

We aim to address some of these research gaps in our Research for Equitable Access and Learning (REAL) Centre at the University of Cambridge. The hope is that this research, together with the commitment of world leaders and civil society, and backed up by financial resources, will lead to real change for the future lives of children with disabilities.

Education is birth right to every individual, Huge education sector, with respect to time it changed a lot, now technology comes to the education sector, like myly app and apps like this are in the market to make smart schools and smart colleges.

But still the world top leaders work hard so education is given to each and every individual around the world. To promote education heavily, developed countries make a step ahead to boost the developing countries education sector.

Thank you for sharing. Good information, I have gain a lot of Knowledge regarding this course.