This blog was written by Jamie Franco Cipriani BSc (Hons), MSc, FHEA. Jamie is an UKFIET Executive Committee member.

As an educator, I have learned that my time is rarely my own. Instead, it weaves around students and their moments of uncertainty. Having taught in Further Education (FE) in England and Higher Education (HE) in China, I am often asked: “What is the biggest difference?” My answer is usually the same. The similarities far outweigh the differences. Across context, students share familiar anxieties, such as securing employment, progressing to postgraduate study, succeeding in assessments and doing better than they did last time. These concerns are shaped by different systems, languages and expectations, yet they are grounded in a shared underlying reality, where young people are navigating an uncertain world. From a critical realist perspective, this reality exists independently of how we describe it, even though our access to it is always partial, mediated through culture, language and history. We may never completely grasp “truth,” but we can come closer to it through attentive practice.

One of the ways I attempt to do this is by staying that extra minute or so. This might mean arriving late to a meeting or joining a longer queue in the canteen. Yet these small acts of presence often create the conditions for something important to happen. A student stays behind to ask a question they were hesitant to voice, which could be about their writing, their future, or whether they belong. In those moments, I do not feel I should be elsewhere. I know I need to be there. In education, reality is not simply given; it is co-constructed through the interplay of teachers, students and context. Zizek (1993) reminds us that when we abandon “fiction and illusion,” we risk losing reality itself. In classrooms, these interpretive “fictions” take the shape of shared narratives about progress, success and possibility. They are not falsehoods, but necessary frameworks that allow students to orient themselves within complex education worlds.

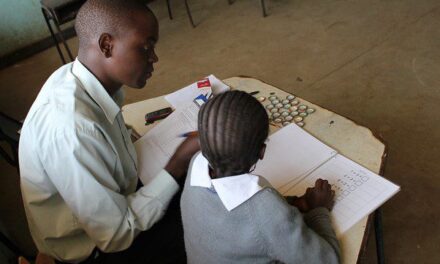

This is particularly evident when teaching in a second language. Working with Chinese HE students, patience becomes a methodological stance rather than a personal trait. Questions may emerge slowly or indirectly. Words may be missed. Meanings may need to be revisited. Rather than seeing this as a deficit, I have come to understand repetition, rephrasing and calm persistence as forms of pedagogical care. Staying a little longer allows these interpretive bridges to form. My approach to teaching is also shaped by inheritance. A central question underpinning my broader research is: How do my ancestors influence my teaching practice? Autoethnography enables me to explore this question by recognising that identity is shaped rationally, across time as well as space.

Drawing on Ricoeur’s notion of Oneself as Another, becoming oneself involves being addressed by others, those present in the classroom, but also those who came before us. These “others” include ancestral figures whose experiences continue to echo through stories, silences and embodied values. Hirsch’s work on postmemory, developed in relation to the intergenerational transmission of Holocaust trauma, offers a powerful way of understanding how the experiences of previous generations can shape the ethical outlook, affective dispositions and sense of responsibility of their descendants. Even though the historical contexts differ, the principles remain, as trauma displacement, conflict and exclusion do not end with those who directly experience them. They travel.

My own teaching practice unfolds across multiple localities, from UK FE classrooms, Chinese HE lecture halls, and cultural inheritances of Italy, Northern Ireland and England. This translocal navigation means that knowledge is never singular. It is practical, experiential, narrative and theoretical at once. Staying that extra minute is therefore not simply a matter of time management; it is an ethical response shaped by social history, cultural memory and present demands. Education always involves tension: between student agency and the world’s demands, between care and interruption, between what students want and what they may need to face up to. Staying a little longer does not resolve these tensions. But it does acknowledge them. In doing so, it affirms teaching as a relational, historically-situated practice, one that seeks not certainty, but attentiveness to what the moment, and the world, asks of us.

Sometimes, leadership in education is not about moving faster. It is about choosing to stay.