This blog is written by Kris Stutchbury, with Clare Woodward, John Phiri, Francis Sampa, Olivier Biard and Lore Gallastegi.

Joseph is the new headteacher of a rural primary school in Central Zambia. He faces many challenges. The school has recently been connected to the mains water supply but has no electricity. In his first few weeks, he was visited by Martha, the District Education Standards Officer, who highlighted the fact that last year’s exam results at the school were very poor. She tells Joseph that the problem is that his teachers need to improve their teaching but don’t attend the regular teacher group meetings that are part of the teachers’ contract. The revised curriculum, asking for more learner-centred approaches with an emphasis on skills and values alongside knowledge is not being implemented. Joseph feels under great pressure from all directions – how can he be a leader of teaching and learning when his life is dominated by the practical issues arising from poor facilities?

In his previous school, Joseph had been part of a project (Zambian Education School-based Training – ZEST) to enhance the regular school-based continuing professional development (SBCPD). Through the resources provided and activities that were encouraged and supported, Joseph had come to understand what ‘being more learner-centred’ meant. There are many definitions available, many of which focus on the learner. But his teachers had found the idea that ‘learners take responsibility for their own learning’ or ‘learners have more autonomy’ problematic. What do they actually have to do and how could they do it?

The Enhanced SBCPD programme (OpenLearnCreate: Active teaching and learning for Africa: ZEST) is based on a set of ‘minimum criteria’ for a learner-centred lesson (adapted from Schweisfurth, 2013, p146[i]). These are:

- Lessons are engaging and motivate pupils to learn.

- Classroom relationships are based on mutual respect.

- Learning challenges pupils and builds on existing knowledge.

- Dialogue is used in teaching and learning.

- The curriculum is relevant to learners’ lives and values a range of skills including critical thinking and creativity.

- Assessment tests a range of skills and gives credit for more than recall of knowledge.

These criteria are underpinned by a set of values and beliefs about learners and learning, including the belief that all learners can learn with the right support and that learners are not empty vessels waiting to be filled. They bring to class interests, experiences and abilities that need to be developed. Through ZEST, teachers have found that if they ask more open questions, for example, give learners time to think or discuss in pairs, and walk around the room while they do so, they elicit new responses. Over time, this and other approaches which promote dialogue, have changed their attitudes to their learners.

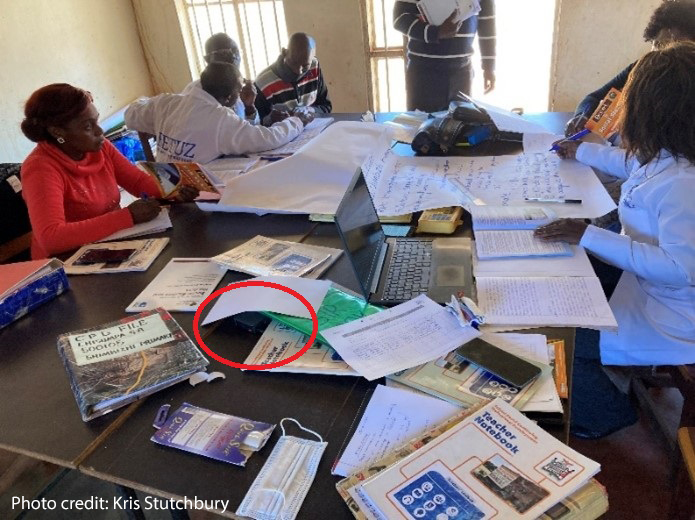

A teacher group meeting in a school in Zambia. The school has no electricity but teachers are using digital resources available on their laptop and phone by connecting to a Raspberry Pi computer (circled in red).

By relating the local school context to learning, children are more willing and able to share their own experiences. Many teachers have commented that children they had thought of as ‘slow’ or ‘shy’, could contribute more than they expected. This realisation has stimulated further changes in practice, more detailed planning and more conversations in the staffroom about teaching and learning. Working as part of the ZEST programme, Joseph came to appreciate his teachers more – just as they had come to appreciate their learners. He has come to understand that they need support in developing their skills to teach the revised curriculum. So the implication from Martha, that the teachers are responsible for the poor examination results, upset him.

Joseph’s experience highlights a common issue across education systems with a high degree of control from the centre in which many involved in international development have worked. This manifests itself through directives (which often don’t take account of local conditions) and monitoring which is not accompanied by constructive support. The attitudes and beliefs expected of teachers are not always played out by those whose role is to support teachers – the focus is on telling teachers what to do, rather than supporting them in how to do it. The ‘minimum criteria’ provide some help here. We suggest that they can be re-written for teachers and that effective instructional leadership should:

- provide access to CPD which is engaging for teachers and motivate them to focus on their teaching;

- be conducted in an environment of mutual respect;

- recognise teachers’ existing expertise and challenge them to improve their skills;

- provide opportunities for dialogue and collaboration;

- be mindful of the context and needs of the teachers in their school; and

- give credit for a wide range of different achievements.

These criteria are underpinned by a set of values and beliefs about teachers, based on respecting their knowledge and experience, and acknowledge the complexity of teaching. They serve as a guide for those with responsibility for supporting schools and teachers. They model the attitudes and values expected of teachers towards learners, providing more coherence and consistency across the system.

This view of instructional leadership is at the heart of ZEST and is changing the way in which head teachers and district officers work with teachers and schools. Effective head teachers delegate the organisation of enhanced SBCPD to the school in-service coordinator, leaving themselves free to concentrate on practical issues. Joseph, however, was very aware that he had no experience of the active teaching approaches his teachers were being asked to try. So he made sure that he attended the meetings himself and sought to learn with his teachers. Another dimension, of instructional leadership, perhaps, is humility – the willingness to recognise the learning required and to engage with the resources that the teachers are using.

[i] Schweisfurth, M. (2013). Learner-centred education in international perspective: Whose pedagogy for whose development? Routledge.