This article was written by Yifei Yan, Lecturer (Assistant Professor) in Public Administration and Public Policy at the University of Southampton, United Kingdom. She is also the author of Getting schools to work better: Educational accountability and teacher support in India and China. This article was originally published in the East Asia Forum Quarterly, Vol.16 (No.1), January–March 2024 on pages 27-29.

Unlike some of its neighbours, India has long neglected its primary and secondary education sector. While progress has been made towards achieving universal education since the 1990s as the neglect got substantially remedied, learning outcomes still remain poor and quite uneven between government and private schools as well as across different states and regions and socioeconomic circumstances. For example, even in as late as 2018, nearly half of Standard V students in rural areas cannot read Standard II-level materials, and less than one-third can do basic division. Education quality and equity is further hindered by issues like teacher absenteeism and a rigid curriculum that prioritises rote learning and benefits students with higher academic achievement.

Given how widespread and multifaceted these problems are, their solutions need a comprehensive and systematic approach. The Indian Government’s National Education Policy (NEP), launched in 2020, offers refreshing ideas, particularly in terms of integrating different stages of schooling and supporting key stakeholders, to achieve educational improvements.

More than three years since its release, the NEP’s ambitious policy prescriptions are gradually reaching the Indian schools on the ground. But analytical, operational and political gaps must also be addressed for the NEP’s vision to be realised fully.

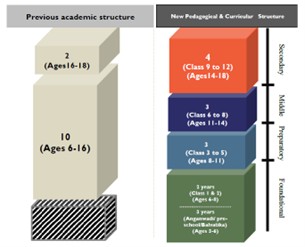

Compared to its predecessor which was issued more than three decades ago, the NEP makes more coherent connections among different stages of school education with children now taught across four schooling levels—foundational, preparatory, middle and secondary. Within this new structure, the preschool level is embraced as an integral component of foundational education—reflecting realisation of the importance of early personal development for a child’s schooling journey. This more integrated schooling structure is expected to better facilitate the coordination of policies for specific schooling stages to ensure that graduates from the previous stage are ready for the next.

Another feature of the NEP is the recognition that ‘no stage [of school education] will be considered more important than any other’. Important as this recognition is, it is unconventional, especially given India’s long-prevailing ‘vertical’ career path for teachers, where promotion means being ‘upgraded’ from teaching in primary schools to teaching in secondary and senior secondary schools.

Complementing this broad vision, the NEP highlights that ‘all stages of school education will require the highest-quality teachers’. It specifies how teachers shall be supported in terms of their service environment, working conditions, professional development and career progression.

While this vision reflects growing international acknowledgement of the importance of empowered and effective workforces, it is unusual in India, where bureaucracies and public servants are often blamed for poor public service delivery. As negative perceptions of teachers are particularly shaped and strengthened by teacher absenteeism, policies usually seek to tighten teacher accountability through the introduction of contract teachers, check-in cameras and school monitoring.

The NEP is similarly committed to supporting students across their entire schooling. While the need to ensure universal access continues to be underscored, the NEP has also attached great importance to foundational literacy and numeracy skills. This aims to tackle widely reported learning deficits.

These ambitions for improving student learning outcomes are put forward without neglecting or compromising students’ learning experiences. Instead, the policy has set out multiple paths for a diverse, flexible and inclusive curriculum to enable the holistic development of students. The National Curriculum Framework for School Education, released in August 2023, is expected to be an essential tool for standardisation and benchmarking. Yet, the NEP has also created space for the curriculum to cater to local contexts and frontline curriculum needs.

Despite this and other positive developments at the federal level, the NEP’s implementation has faced intense resistance from states such as Karnataka, Tamil Nadu and Bihar. In other words, although there is strong political commitment at the top, the ability to communicate and coordinate with state governments has fallen short.

The NEP’s controversial reception at the state level is not only an issue of political capacity, it also reflects a deficit in policymakers’ operational capacity. Apart from expecting the states to assume responsibility for tasks ranging from curriculum development to teacher support, little clarification is provided in the NEP on the resources and support that state governments can expect from the central government to help them effectively carry out these functions.

The NEP is also troublingly vague on the design of policy instruments that will encourage a shift away from ‘vertical’ teaching career paths, achieve learner-centred and curiosity-driven pedagogy or facilitate sharing of best practices between public and private schools.

These deficits point to an urgent and more fundamental need for both central and state governments to fill in the gaps regarding their analytical capacity. For instance, the usefulness and relevance of national-level datasets for policymaking have been hampered by discrepancies in definitions and estimation methodologies. At the state level, research has also highlighted how the official data on standardised assessments can overestimate the levels of student learning. Such shortfalls in data, if left unrectified, will make it difficult to advance the NEP’s policy goals. Similarly, to support the launch of a tailored curriculum, policy makers and education officials must also improve their capacity to determine the current status and identify gaps in teacher recruitment and preparation for new subjects.

Without corresponding policy efforts to address these gaps and strengthen capacity, a solution that is lauded as having great promise for making India ‘a global knowledge superpower’ risks falling short of expectations.