This blog was written by Rhiannon Moore, The Open University and University of Bristol, and based on a presentation given at the UKFIET 2023 conference.

Some context…

When I began my doctoral studies in September 2018, my intention was to use secondary quantitative data from the Young Lives India 2016-17 school survey to address questions relating to teacher ‘effectiveness’ in Andhra Pradesh and Telangana, India, and to complement this with primary interview data collected from teachers. Fast-forward 18 months into the COVID-19 pandemic, however, and suddenly a trip to India to interview teachers was no longer possible – as with so many other studies, my PhD research needed to adapt to incorporate the voices of those from other countries at a time when international travel just was not a possibility.

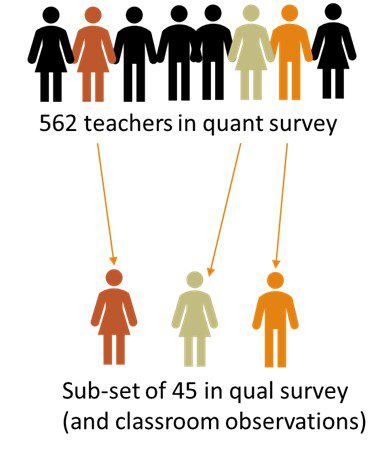

Discussions with friends, colleagues, and a number of education experts in India led me to address this challenge by incorporating two additional sources of qualitative data in my study: firstly, secondary qualitative questionnaire data from teachers collected by Young Lives in 2017-18 as part of a classroom observation sub-study; and secondly, primary interview data from education stakeholders working at state and national-level in India[i]. This blog post (and the UKFIET 2023 presentation which it stems from) focuses on analysis of the first of these: secondary qualitative questionnaire data from 45 teachers in Andhra Pradesh and Telangana, which has been linked to quantitative school survey data from a larger sample of 562 teachers (see Figure 1).

The analysis and findings

This part of my PhD research used mixed methods analysis to examine factors associated with ‘teacher effectiveness’ in Andhra Pradesh and Telangana, a context in which the role of the teacher is challenging, contradictory and rapidly changing. It focused on three ‘teacher intermediate outcomes’ identified as important for student learning: professional knowledge, absence from the classroom, and the classroom instructional environment, and considers the role which these may have in understanding underlying processes of teacher effectiveness.

The quantitative data which was used for the majority of the analysis I present here was explored using a three-level multilevel regression model, locating teachers within their schools and mandals[ii]. The qualitative data meanwhile, was explored using an iterative process of inductive and deductive thematic analysis, with themes generated from the data considered alongside patterns within the linked quantitative data. These complementary analyses suggested distinct trends in the factors associated with the ‘intermediate outcomes’, indicating that each is shaped by factors at different levels of effect:

- Teacher professional knowledge is most strongly associated with school context, indicating some potential ‘sorting’ of teachers into schools. These include school management type (teacher professional knowledge is lower in private schools) and school location (it is higher in urban schools).

- Teacher absence from the classroom relates to a combination of power (teachers who are male, more senior, better qualified, union members are more likely to be absent) and powerlessness (those working in remote rural schools they did not choose to teach in are also more likely to be absent). These suggest absence may relate more to systemic factors than individual choices.

- Teacher classroom instructional environment (from the quantitative data) appears predominantly associated with individual-level factors, such as qualifications (better qualified teachers have higher classroom instructional environment scores), self-efficacy (higher efficacy is associated with higher scores) and experience (more experienced teachers have lower scores). It does not seem to vary by school type.

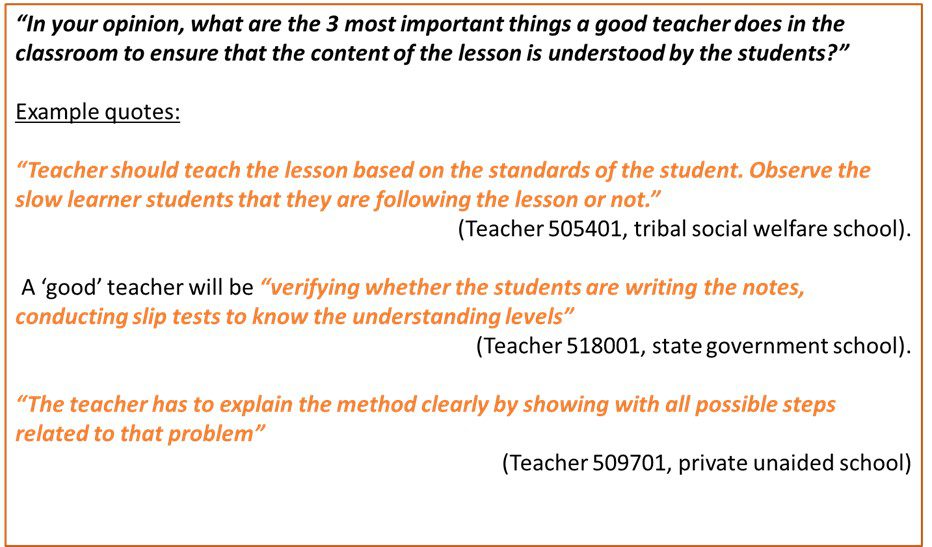

- Teacher views of ‘effective teaching’ practices (from the qualitative data), in contrast, vary considerably by school type. Teachers in tribal social welfare schools emphasised ‘equitable learning’, while state government and private aided school teachers appeared to prioritise ‘productivity’ and completion of the curriculum. In contrast, ‘teacher-led learning’ was the focus in private unaided schools. Figure 2 gives some quotes exemplifying this pattern.

Analysis also finds that these three teacher ‘intermediate outcomes’ are largely uncorrelated: teachers with higher absence are not necessarily those with lower classroom instructional environment or teacher professional knowledge scores. Likewise, those with high teacher professional knowledge do not necessarily have a more positive classroom environment (as reported by students).

Some concluding thoughts

Findings from these mixed methods analyses indicate that there are important differences in the factors associated with these three teacher ‘intermediate outcomes’, with each associated factor operating at different levels. The use of two datasets to examine the classroom instructional environment reveals that this aspect of performance appears particularly divergent, with (qualitative) data indicating that teacher beliefs about ‘effective teaching’ vary by school type, while (quantitative) data on practices used in their classrooms do not (as reported by students). In addition, analyses which find little/no correlation between the three ‘intermediate outcomes’ suggest that there is not one group of teachers who perform highly in all outcome areas, but instead a diverse population who perform in different aspects of their work.

These findings confirm the complexity of processes of teacher effectiveness in this context, and highlight the need to situate teachers within their broader environment if we are to better understand their performance. I feel the incorporation of primary data collected from education officials and other stakeholders helps to add an additional dimension relating to this to my PhD – an unforeseen benefit of the changes the pandemic forced me to make! However, these findings also indicate the importance of examining the multiple ways in which teachers appear to be ‘effective’ using multiple sources of data at different levels. This leads me to my final reflection in this blog (and the accompanying presentation) – if I had a magic wand giving me the ability to add something further to my PhD research at this point, it would be a dramatic increase in the presence of teachers’ voices throughout to interrogate and expand upon other findings. Perhaps this is somewhere my research journey can take me next…

[i] This latter group were chosen as I was more able to make contact with them remotely through existing networks.

[ii] A mandal is a sub-district administrative area in Andhra Pradesh and Telangana; schools were randomly sampled within mandals for the Young Lives survey.