This blog was written by Deborah Cooper, Lecturer in International Education, in collaboration with Freda Wolfenden and Saraswati Dawadi, Open University, UK. It is based on a presentation given at the UKFIET 2023 conference.

Istanbul, where East meets West, was the hub where our global research team came together in 2023 at last, after two years of remote work on scalable approaches to inclusion. The focus of the workshop was a deep dive into data analysis on the GPE KIX Empowering school leaders as local change agents for equity and inclusion project 2021-2024. The qualitative and quantitative data on the table from school leaders in Pakistan, Nepal, Afghanistan* came alive through the rich discussions of daily leadership challenges in different contexts.

As our UKFIET presentation outlines, the expectations of what school leaders can or should do about inclusion varies. This can be due to an administrative outlook, for example collecting attendance data to report rather than make changes. Or school leaders, despite compassion and nuanced localised understanding of how poverty and marginalisation impact communities, may not see it as their role to implement far away national inclusion policies. “If we get government orders along with resources and funding, we can do it. Otherwise, we can’t work on inclusion by ourselves” (Pakistan).

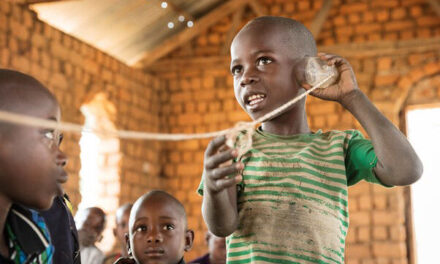

How can leaders be supported to initiate small local changes in schools and classrooms in ways that provide agency and have the potential for scaling? What happens with a bottom-up approach to change and how far does the status quo move in communities?

This model moves beyond a deficit view of school leaders who have not received formal training in inclusion and builds on their local understandings of inclusion. Support is key and this is provided via professional hubs, Networked Improvement Communities (NICs) and translated open resources on inclusion. To design appropriate resources we conducted an initial survey – this indicated that, although school leaders used phones for personal use, working with other leaders through online resources and in face-to-face facilitated groups to identify inclusion challenges, was a new form of professional development.

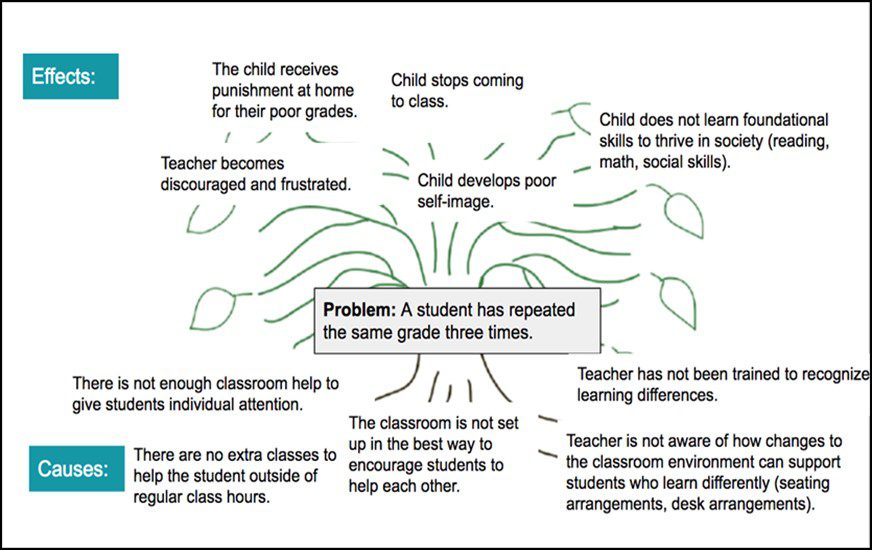

Unlike a traditional course, leaders are active in conducting an inclusion audit in their school, with time to review disaggregating data, conducting classroom observations and engaging with the community in order to come up with an inclusion challenge to work on. The facilitated networked groups provide a safe place to share progress and issues. Leaders have choices and the Plan Do Study Act cycle gives leaders room to innovate in contexts rather than imposing a rigid definition of inclusion as in a traditional course. The use of a problem tree helps deepen discussions on root causes.

The initial analysis shows some shifts in leader agency and constructions of inclusion, for example:

- In a primary school in a rural area of Nepal, a leader focused on supporting access and registration to the many children without birth certificates, through engaging local government.

- In a rural middle school in Pakistan, a leader supported teachers who were reluctant to make changes to include the poorest and working street children in school. They engaged with parents, teachers and religious leaders to provide more flexible hours.

- In an Afghan refugee camp school in Pakistan, leaders spoke up about the language of instruction issues.

- In a private school of Afghanistan students in Pakistan, the school leader worked on staff attitudes and bullying of Shia and Suni backgrounds despite some pushback.

In all contexts, country teams are exploring scaling up the intervention with relevant stakeholders. These challenges suggest that given the right support school, leaders have the potential to grow beyond an administrative perspective to taking ownership and initiative.

*Note: Following the Taliban take over the 2021 the project has shifted to working with school leaders in the Peshawar area of Pakistan who are educating displaced Afghan children.