This blog was written by Dr Ruth Naylor, independent consultant and previous Chair of the 2021 UKFIET conference. It is based on a session at the 2023 UKFIET conference.

Inclusion of refugees in national education systems is seen by UNHCR, and many others, as the most sustainable solution for protecting refugees’ right to education. But when a low-income country is faced with a sudden influx of hundreds of thousands of refugees, accommodating them in national schools can be a major challenge, especially when schools in the hosting area are already overcrowded and under-resourced. Even where policies are supportive of inclusion of refugees, urgency can trump sustainability in the initial education response. The humanitarian sector sometimes still needs to set up temporary parallel education provision for refugees so that education does not wait.

But a few years into a refugee crisis, with diminishing humanitarian funding, and little prospect of safe return, hosting governments, humanitarian and development actors, local and refugee communities face multiple dilemmas in agreeing and developing a long-term sustainable solution for refugee education. Where should refugee children learn? Which curriculum? Which language? Who should teach them? And, perhaps most critically, who should pay?

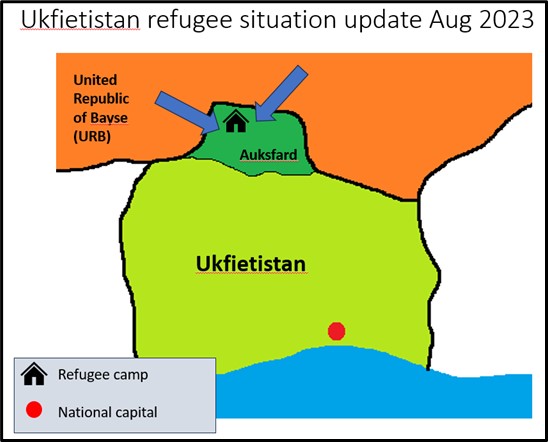

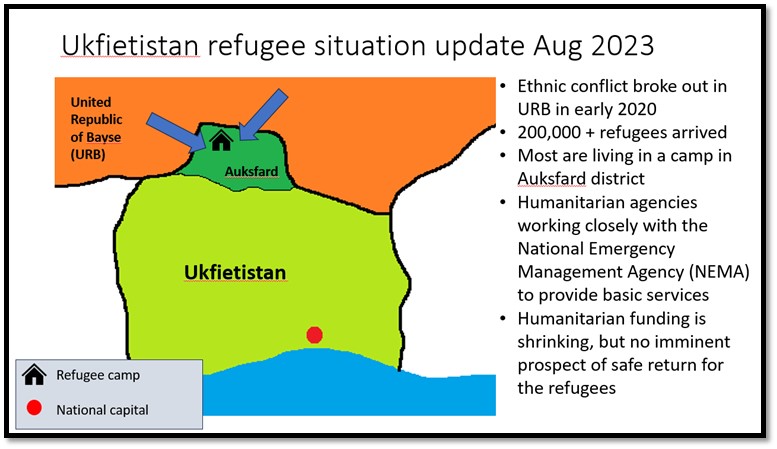

In our “Inclusion Dilemmas” workshop at the 2023 UKFIET conference, participants were asked to grapple with these dilemmas from the perspectives of a range of stakeholders. We presented a refugee scenario in a fictional low-income country (see Figure 1). Each participant was allocated a role then invited to join either the Refugee Sector Education Working Group or the Local Education Group, both tasked with agreeing on a 5-year plan for refugee education. There was a broad consensus that inclusion of refugees into local schools was the best way forward. But reaching agreement over how this could be achieved required negotiation. In some cases, solutions were found relatively easily. For example, the World Bank representative agreed to fund the construction of new classrooms in local schools, and the Church representative offered the use of Church buildings as temporary learning spaces to avoid the need for double shifting whilst the classrooms were being built. But other problems were more “wicked”, in particular: who pays the salaries for the additional teachers that local schools would need to recruit?

The 2018 Global Compact on Refugees, is based on “… the principles of burden- and responsibility-sharing.” In other words, richer countries should share the financial costs incurred by poorer countries that host the majority of refugees. The UNHCR and the World Bank estimate that it would cost around $4.85 billion a year to include all refugee students in low- and middle-income countries within national education systems. Although this sounds like a lot of money, it is a relatively small amount compared to other areas of global international aid. For example, it is roughly the same as the amount of Official Development Assistance that the UK government currently spends on supporting refugees and asylum seekers within its own borders (£3.7 billion or $4.5 billion).

In recent years, new funding mechanisms, such as the International Development Association’s Window for Host Communities and Refugees, have been developed so that donors can share some of the initial costs of including refugees in national schools: such as building new classrooms, teacher training and running bridging courses. But examples of where richer countries “share the burden” of the recurrent costs of educating refugees in national systems are much harder to find (with the exception of refugee hosting countries bordering Europe). Salaries are the biggest recurrent cost in most education systems. But many of the major donors refuse to fund these.

Public spending on education is an investment, as it yields huge social returns. But with refugee education, it is difficult to predict which country will benefit from the social returns on investment. So, we need to think of investing in refugee education at the global level. Since the returns on investments in refugee education are global, investment in the recurrent costs of education should be shared by the global community. If multilateral donors and high-income countries are serious about the Global Compact on Refugees, and remain committed to the inclusion agenda, they need to rethink how the recurrent costs of educating refugees are shared.