This blog was written by Dr Luisa Ciampi and Professor Pauline Rose, REAL Centre; Dr Loveness Chimuka and Oberty Maambo, Altamont Group; and Dr Nkanileka Mgonda, University of Dar es Salaam.

The University of Dar es Salaam, Altamont Group, and the REAL Centre at the University of Cambridge have been working in collaboration with CAMFED on a research project to understand if and how CAMFED’s Learner Guide Programme can be scaled up in Tanzania, Zambia, and Zimbabwe.

In this blog, we provide a taster of key findings from this research. These are presented in more detail in country-level briefs for Tanzania, Zambia and Zimbabwe, with a regional overview highlighting the commonalities across the countries.

Despite positive shifts in access to education in sub-Saharan Africa, many marginalised children are still not learning the basics. This challenge has deepened as a result of the disruption of COVID-19 with particular effects on girls.

A recent blog post identifies that many programmes are having an impact on learning, but are only operating on a small scale, and the evidence collected suggests that many of these interventions are not designed to take into account the realities of government systems at scale.

Getting programmes that work to scale and integrated into national systems so that they can support long-term and systematic change is difficult for many reasons. These can include sound intervention design, local leadership, political will, and space for adaptability and reflexive learning.

With this in mind, a team of researchers has been working together with CAMFED and government officials in Tanzania, Zambia, and Zimbabwe to identify how governments can adopt and sustainably scale up elements of the CAMFED Learner Guide Programme, as relevant to them.

What is the Learner Guide Programme?

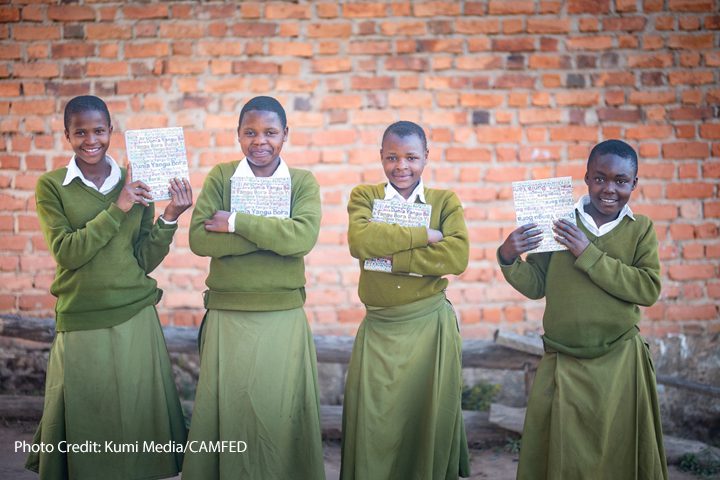

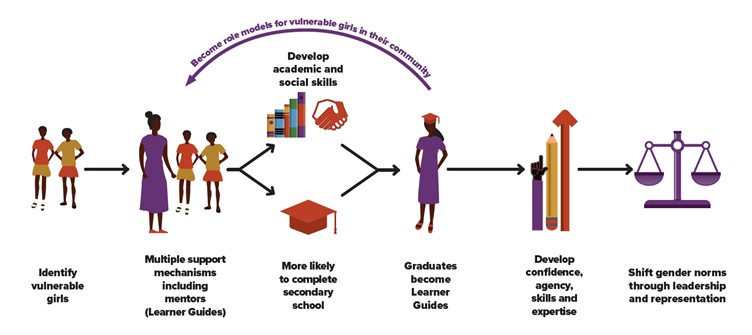

The CAMFED Learner Guide Programme aims to support girls in government secondary schools to strengthen self-development and foundational learning by financially and socially supporting them to stay in school. The primary support mechanism is provided by recent school graduates called Learner Guides, who went through the same CAMFED programme during their secondary education. In addition, some school graduates have been recruited as Learner Guides who were not previously supported by CAMFED. These graduates volunteer in their school to help other children in their studies by delivering a life skills and wellbeing programme called My Better World, and providing peer-to-peer mentorship to students, as well as taking on roles within school and community committees. As an incentive for volunteering, the Learner Guides also receive access to interest-free loans which open business opportunities for them.

Figure 1: CAMFED’s Learner Guide Programme

Why focus on the Learner Guide Programme?

Evidence suggests that CAMFED’s programme results in improved retention and learning outcomes, and that it is cost effective. Learner guides are recognised as role models in their communities. Given the identified success of the programme, it is appropriate to consider how to ensure it can reach even more marginalised girls through government systems.

What was our research design?

Using CAMFED’s long-established networks with governments in Tanzania, Zambia, and Zimbabwe, we established a Scaling Advisory Committee in each country. These committees include key government officials from different ministries (including ministries of education, youth, and community development) to work together to explore if and how the Learner Guide Programme is scalable. The Scaling Advisory Committees continue to meet after the research was completed.

Government officials who are part of the Scaling Advisory Committee were tasked with engaging in data collection activities including attending Scaling Advisory Committee meetings and participating in interviews and school visits. As part of the research process, they also contributed to developing questions to ask teachers, students, parents, and Learner Guides during the school visits, and participated in asking these questions. Throughout the research process, they shared their reflections on the Learner Guide Programme during Scaling Advisory Committee meetings to identify the opportunities and challenges for scaling up this intervention.

What did we find?

All government officials from all three countries who participated in the Scaling Advisory Committees identified that the Learner Guide Programme aligns with national education priorities in three common areas:

- Equity within education

- ‘Life skills’ to support learners after school

- Supporting guidance and counselling services.

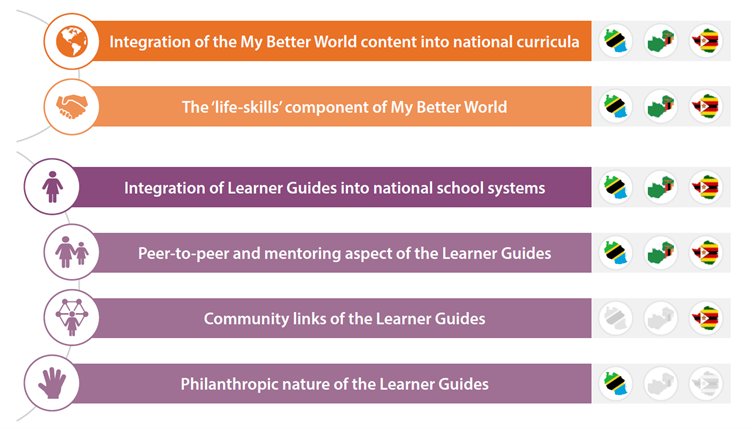

Across all three countries, government officials noted that it is important to prioritise integrating both the Learner Guides and the My Better World into their national education systems.

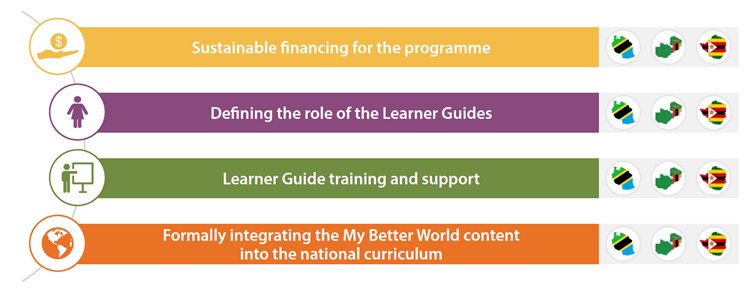

Figure 2: Areas of the Learner Guide Programme for prioritisation

However, the practicalities of this integration require further consideration.

The overarching concern between the three countries about supporting the scaling up process of the Learner Guide Programme was the need for it to be financially sustainable. If it is viable to run the programme in its current form at scale, then provision of training and support for the Learner Guides needs to be considered so that national education standards are formally met by the Learner Guides.

If it is not financially viable, then the roles of the Learner Guides, teachers, and guidance and counselling teachers would need to be reconsidered for an adapted version of the programme, with teachers potentially delivering the My Better World Content, and with guidance and counselling teachers providing the social support aspect. However, it is noted that this version would lose the peer-to-peer aspect provided by the Learner Guides.

There is also a need to consider how to integrate the My Better World programme into the national curricula formally, ensuring that there is no duplication between existing national curricula on life skills topics and identifying ways to overcome challenges of formally timetabling My Better World lessons in already overloaded school timetables.

Figure 3: Areas of the Learner Guide Programme for further consideration

Importantly, government officials identified ways to support the feasibility of scaling up the Learner Guide Programme. These include ensuring continued and strategic advocacy to grow awareness of the Learner Guide Programme, and to provide opportunities for further engagement to enable scaling up. They also suggested addressing the financial viability of the process of scaling up by leveraging relevant ministries beyond the ministries of education (which are often overstretched), such as ministries of youth and community development, building on community funding models, and making use of existing volunteer support mechanisms.

Why do our findings matter?

While concerns about financial sustainability for scaling up programmes are well known, our findings show that working in collaboration with researchers, implementers (such as CAMFED), and governments can help ensure that initiatives that have contextual relevance can potentially adapt to fit with local needs and priorities. It further demonstrates how partnerships that enable linking research and implementation approaches together can support understanding and engagement, which is an essential foundation for scaling up.

Whilst there remains work to be done in all three countries for the Learner Guide Programme to be formally adapted and adopted, this research provides a strong springboard for key decision-makers to work from, and we can’t wait to see what happens next!