This blog was developed on behalf of the Tauwhirotanga team – the Monitoring, Evaluation and Learning (MEL) partner team in the Porticus-funded global programme on Education in Displacement (EiD) – called All Eyes on Learning (AEoL). Written by Mieke Lopes Cardozo with support of Ritesh Shah, Julie Chinnery, Jennifer Flemming, Kayla Boisvert and Tarek Tamer.

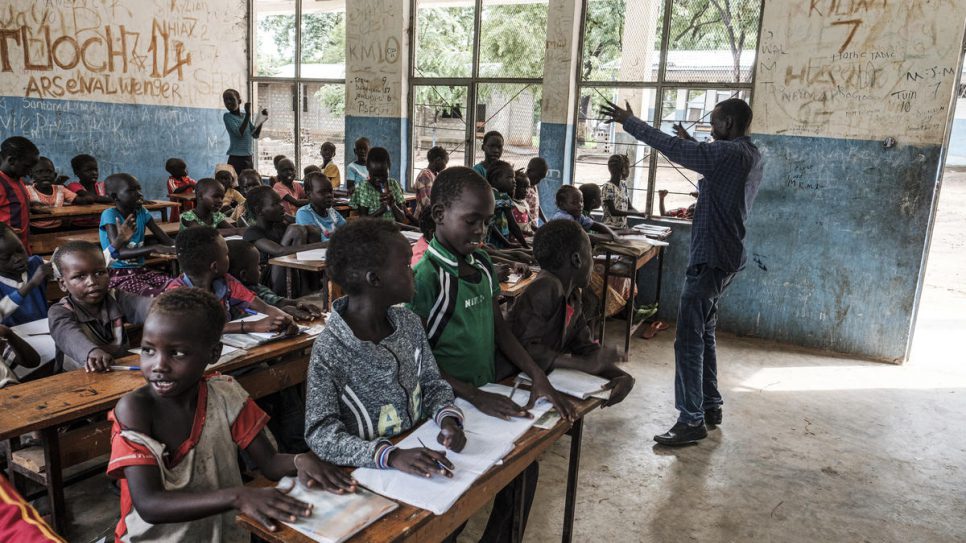

We invite you to imagine… what could be the potential for more meaningful systems change, if refugee learners and populations would no longer be considered as a ‘problem’ to be solved, yet rather as an opportunity to exploring the potential for wider systems and structures in which displaced learners are hosted as potential pathways for more thriving communities and ecosystems? Such a mindshift requires a radical and perhaps philosophical rethinking of both how we understand the education system for refugee learners, how we work within it and perhaps most importantly – our own internal patterns of thinking about change and development in relation to education systems – or human development more generally.

With a team of six colleagues, representing the Tauwhirotanga team – fondly referred to as the T-team – we formed the Monitoring, Evaluation and Learning (MEL) partner team in a large-scale global philanthropic programme from Porticus focused on holistic learning outcomes in Education in Displacement (EiD) – called All Eyes on Learning (AEoL). As we embarked on this journey, we asked ourselves:

1) What restraints and potentials did we recognise at the outset for meaningful collaboration and reflective learning to inform our MEL design (as nested within overall programme design and the funders’ overall strategy)?

2) What greater value does the MEL work aim at, and how do we see this contributing to an increased ability of partners to address the changing EiD ecosystem dynamics?

3) How do (or can) specific MEL approaches (including Regenerative Design, Outcome Harvesting, and Most Significant Change methodologies) contribute to the goal of collective learning on/in EiD ecosystems?

4) What shared sense of direction or vocation has guided our overall MEL work, in how far has this been or does this need to be evolved moving forward?

Three dimensions of an ecosystems approach to learning

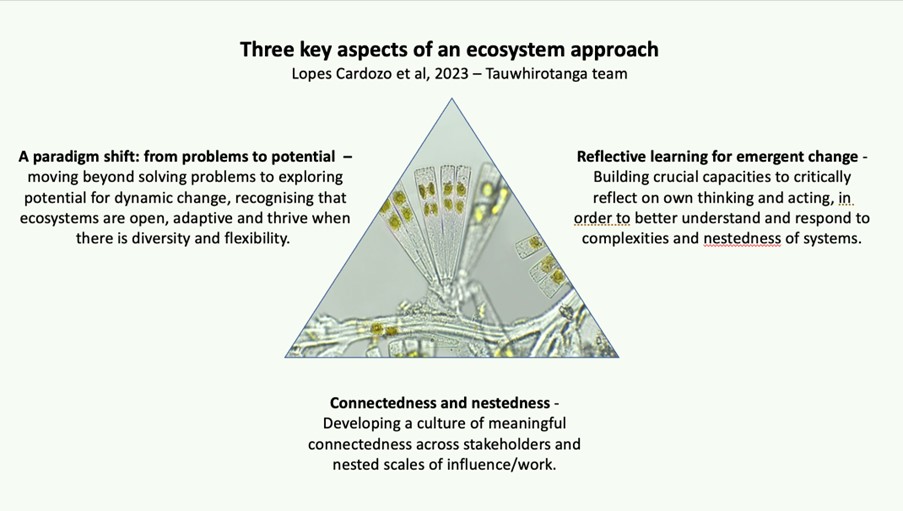

As MEL partners, and in collaboration with other partners, we developed an approach which we collectively came to name an ‘ecosystems approach’, which consists of three interrelated aspects.

- First, as we recognise that ecosystems are dynamic, adaptive and thrive when there is diversity and flexibility, we hence need to move beyond a problem-solving mentality into seeking potential for transformation – which requires a paradigm shift. Drawing on regenerative development and design theory (Sanford, 2022; Mang and Haggard, 2016), we adopted a living systems approach to reflect on our motivations, aspirations and functioning in relation to the EiD ecosystem as a field of endeavour.

- Second, taking an ecosystem approach to programming requires developing meaningful connectedness across actors and nested scales of influence/work. We invested considerable time in our internal team work around building trust, connectedness within the team. Concretely, in our monthly T-team meetings we structurally worked on what is called ‘external consideration’ and engaged caring as a framing for our ways of working and building partnerships. Examples of questions we worked with are: what is the core/essence of our MEL work in AEoL? How can we best support others (in our T-team, partners, the AEoL/EID community) to develop their agency/will for change? How can we best support others/the collective to express their/its potential?

- Third, we focused on building capacities to learn and better understand complexities and nestedness of systems change, and accounting for this through programme design, implementation, management, and continuous developmental learning. Within the MEL team, we worked with a range of reflective questions and socratic methods – working more structurally on reflective self-accountability – without losing sight of the structured environment we engage with. Examples of questions we engaged with include: What is my part in this situation? How can I hold myself accountable (for effects of my actions)? Who am I in this situation? Can I stay away from judgement (good/bad – guilt/blame/shame), and practice unattached self-reflection? What is my inner ‘direction’ required in this situation? Who (what version of me) do I need to bring?

Designing developmental learning in ourselves and between partners

By collaboratively working on such reflective questions as a continuous process of self-accountability and developmental learning, this blog aims to hold a mirror to ourselves and to the goals we set out to achieve as a MEL partner. Specifically, we hone in to the learning-oriented components of our work and analyse what it takes to build ownership across stakeholders over an ecosystem-geared approach to engagement in the EiD community. Drawing on regenerative development and design theory (Sanford, 2018; Mang and Reed, 2012), this requires moving out of organisational silos and competition for scarce funds—and reminding ourselves of the interconnected, interdependent, dynamic and symbiotic relationships we hold with each other.

Over this period, we aspired to build collective ownership, engagement, understanding and eventually action on the premise that systems transformation – in our case in the EiD ecosystem – cannot be done without simultaneous transformations of the ways in which we learn, think and act ourselves (Mang and Haggard, 2016). Following an auto-ethnographic inspired approach (Cann and DeMeulenaere, 2012), we trace back our efforts over the past three years to support a shift in mindsets, actions and attitudes, within our own team, and those of other programme partners.

This translated then in our work with partners into online and in-person developmental and reflective learning exercises, designed from regenerative design thinking – and informed by ongoing and needed conversation in the broader field about efforts to localise and decolonise work. In the AEoL Partner Forum in New York last year September, we purposefully invited partners to step into a collaborative, reflective mode of working – and questioning and transgressing the existing patterns of still very much siloed and competitive approaches of work in the EiE/EiD field (Flemming, 2021).

What have we learned and how might this be relevant within the context of the EiD field?

- Process matters beyond just impact. Partner feedback regularly noting that that the processes of reflecting, learning, collaborating and connecting have been useful, relevant and meaningful. This has included the opportunity to question traditional ways of working and conceptual norms, as well as to shift mindsets and attitudes about how change and impact occurs.

- Change requires working with complexity and challenging the status quo. This includes existing hierarchies of decision-making and power structures. Working in a manner that intentionally “slows down” work, as well as that provides the space and time for meaningful collaboration, learning and engagement, takes notable and significant investments and intentional planning of time, money, and human resource. Partners note that unless internal institutional cultures and practices change, and funders support such processes, it will remain difficult to embrace a radically different approach to one’s work.

- Long term, transformational change is focused on building and sustaining movements. Bringing together actors as equal stakeholders with similar transformational goals is critical, especially when they co-create the opportunity to reflect on a shared purpose and sense of direction. When such a larger purpose goes beyond just keeping a specific project aligned and on track towards stated goals or outcomes and rather focuses on a deep shared caring for a larger web of systems—this has the potential to inspire people, teams and organisations to remain committed to the vision for long-term systems change and learn and adapt as needed – especially in the face of multiple wicked challenges and continuing emergencies.

As a final note, the glue that kept us as a team so committed, engaged and caring for the partners and collective aims of the programme, was a shared ambition – which was supported by the Programme Management Team – to approach our work differently, creatively and – perhaps key – to be playful and truly enjoy the process of co-creating and collaborating together.