This blog was written by Siddharth Pillai, Education Programmes Advisor for Street Child in Afghanistan, and Sarfaraz Sahebzada, Executive Director of Keenly Humanitarian Assistance for New Afghanistan (KHANA). With thanks to Ramya Madhavan, Kshitiz Basnet, Hamidullah Ahmadzai and Abdul Rashid Tahiry for their support and contribution to this article.

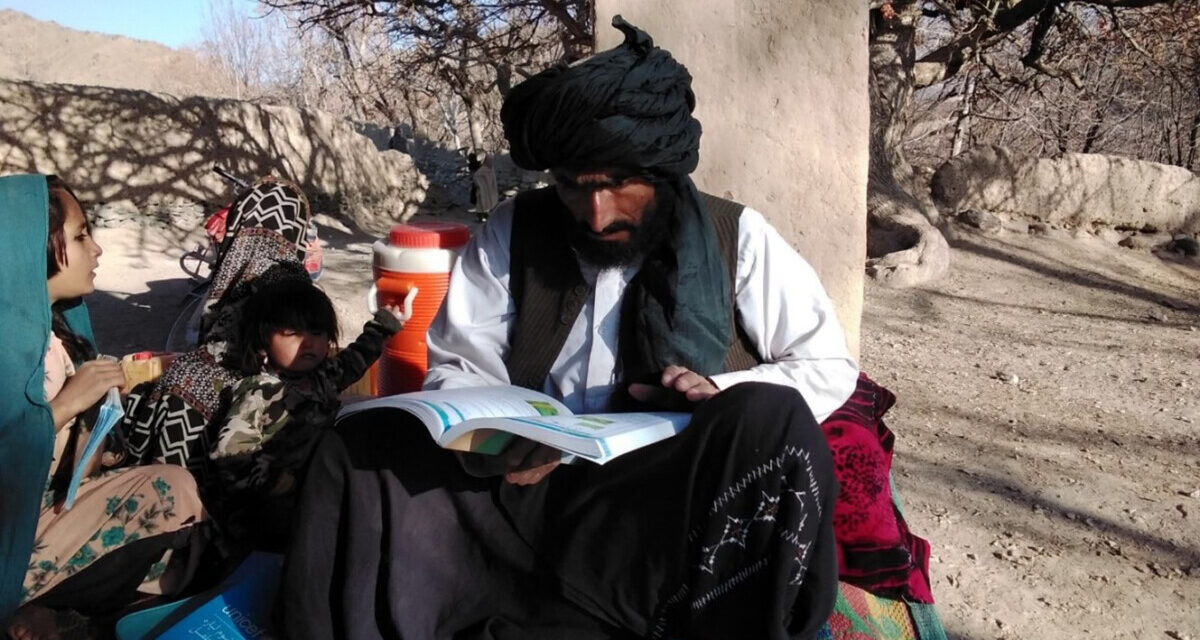

According to UNICEF, 13% of Grade 2/3 students in Afghanistan possess foundational reading skills. While studies have examined the various factors impacting the acquisition of this gateway skill among students, the teaching process has been identified to be a significant factor among them. A World Bank report shows that teachers’ content knowledge and pedagogical knowledge in Afghanistan are poor. Amidst the lack of adequate pre-service training in literacy instruction, pre-prepared lesson plans and instructional guides can serve as crucial resources and a foundational step in assisting teachers with content organisation and the establishment of effective routines for teaching literacy and improving student learning outcomes.

In its report, the Global Education Evidence Advisory Panel (GEEAP) has classified educational interventions featuring structured teacher guides as a “Good Buy”. This designation signifies that there is compelling evidence supporting the cost-effectiveness of these interventions across diverse settings. However, not all teacher guides are equally resourceful. Some are better than others. In Afghanistan, two sets of courseware are used to guide the literacy instruction process: old teacher guides and the new Afghan Children Read (ACR) teacher guides developed under the Afghan Children Read project. Most of the public schools and NGOs in the education space continue the use of the old teacher guides for literacy instruction.

Under the Global Partnership for Education/Education Out Loud-funded South Asian Assessment Alliance, Street Child and its national partner Keenly Humanitarian Assistance for New Afghanistan (KHANA) sought to understand the resourcefulness of the two sets of teacher guides for Grades 2 and 3 for Dari language using the Teacher Guide Diagnostic Tool developed by the World Bank. The analysis done is to support the Ministry of Education, as well as NGOs, to make an informed decisions while choosing teacher guides, as well as to support revisions of the existing set of teacher guides.

As part of our analysis, we examined the overall organisation, structure and level of scripting of the entire teacher guide. Furthermore, we evaluated the make-up of the six sampled lessons of each Grade, focusing on lesson layout, lesson structure and general pedagogical practices.

Our analysis shows that both the old and the new ACR teacher guides have some similarities as well as striking differences.

Similarities in teacher guides

In terms of similarities, both guides are consistently structured throughout, with a consistent routine for lessons with each lesson plan covering one lesson period. Each lesson plan also has visible images of the student book pages embedded into the teacher guide and is less than two pages which increases the usability of the lesson plan. For every 35-40 minutes, both guides recommend less than five activities to avoid information overload and to allow ample time for practice. The activities are also broken down into smaller steps. In terms of pedagogical practices, both guides include instructions on asking teachers to introduce new content or model new skill and they also guide teacher on when and how to check for students’ understanding.

Differences in teacher guides

However, there are striking differences between the two sets of teacher guides, which make it clear that the new ACR teacher guide scores significantly better than the old teacher guide both in terms of ease of use (that is, how the guide supports teachers to deliver content) as well as the quality of the pedagogical practices prescribed in each lesson.

The new ACR teacher guide supports teachers in explicit and systematic instruction on emergent literacy skills. The ACR teacher guide assists teachers in systematically teaching orthographic symbol-sound relations (i.e. phonological awareness, orthographic symbol knowledge and phonics) which has clearly demonstrated a positive effect in low-income countries. The old teacher guide fails to provide explicit instruction on emergent literacy skills.

Regarding the lesson structure aimed at enhancing teacher usability, the old teacher guide lacks proper labelling when introducing new activities. In contrast, the ACR teacher guide effectively introduces each activity with clear labels and accompanying icons. Additionally, the old teacher guide does not sufficiently differentiate between instructions meant for verbal delivery by the teacher and those intended for the teacher’s internal reference. Often, the old teacher guide combines directives on what the teacher should communicate and what actions should be undertaken within the same sentence, thereby diminishing the quality of instructional support offered by the guide. Furthermore, in the older teacher guide, the textual description of activity steps (as depicted in Figure 1) is presented as a lengthy paragraph, whereas the new ACR teacher guide (as shown in Figure 2) presents this information in a bullet-point format. This revised format enhances the teacher guide’s practicality in real classroom settings, particularly for multi-step activities.

Concerning general pedagogical practices, the ACR teacher guide demonstrates a high degree of specificity in its lesson objectives. It employs action verbs, such as ‘Recognise the sounds / at the beginning, middle and end of the word’, to articulate the precise knowledge or skills that students are expected to attain by the conclusion of the lesson. In contrast, the older teacher guides feature more ambiguous lesson objectives, like ‘Reading, writing words, understanding the characteristics of the summer season’. Furthermore, the older teacher guide fails to offer opportunities for guided practice, as not all students in the class are provided with the chance to practice new content or partake in new activities with the teacher’s guidance, even though opportunities for independent practice exist.

While teacher guides do not represent a long-term solution, they serve as invaluable support mechanisms for educators, particularly in challenging contexts like Afghanistan, where both pre-service and in-service teacher training programmes may still fall short in equipping teachers with the necessary skills for delivering high-quality instruction. The new ACR teacher guide, which has been shelved for a few years by educators, offers structured guidance to teachers in implementing literacy instructional practices that have demonstrated their effectiveness in low- and middle-income countries. A transition towards the adoption of this ACR teacher guide by government schools and non-governmental organisations holds the potential to significantly enhance the quality of literacy instruction in Afghanistan.