This blog was written by Deepak Kumar (ASER Centre, India), Suman Bhattacharjea (ASER Centre, India), and Ricardo Sabates (REAL Centre, University of Cambridge, UK).

Achieving basic literacy and numeracy skills is fundamental for successful learning through the schooling cycle. Supporting children to achieve these foundational skills requires not just teachers, but multiple stakeholders working together to enable meaningful understandings and applications of these skills. But, how can multiple stakeholders work together to ensure that children achieve their full learning potential? A project in rural Uttar Pradesh, India, strives to find an answer.

This project, which involves researchers from the REAL Centre at the University of Cambridge and ASER Centre in collaboration with Pratham Education Foundation, explores how school and community-based interventions can raise foundational learning outcomes for disadvantaged primary school children. The intervention attempts to raise awareness regarding the importance of learning for children’s future and aims to promote meaningful and productive interactions between parents and teachers to ensure that a child’s learning is perceived as a social responsibility.

Through this blog, we look at the impact of the programme after a year, on raising children’s foundational skills and investigating how community-school partnerships can build better accountability relationships. We first provide a brief overview and then discuss the effect of community-school partnerships on parent-teacher interactions and exposure (and participation) of children to community-based learning activities in villages. Finally, we discuss the impact of differential exposure to these learning activities on improving the children’s foundational literacy and numeracy levels.

A Randomised Control Trial (RCT) study was conducted in 400 randomly-selected villages in one district of rural Uttar Pradesh, using a longitudinal mixed-methods design to evaluate two interventions. The first intervention focused on activities to build communities’ awareness of and engagement with children’s foundational learning in grades 2–4. The second intervention went further, including community-based activities but also focusing on school actors’ awareness of and engagement with these issues. Villages were randomly allocated to the community intervention, the community-school intervention, or to a control group where no intervention was implemented. The baseline survey included around 24,000 pupils from grades 2–4 from 853 government primary schools in 400 villages. At baseline, none of these students were able to read a simple text at grade 2 level of difficulty; the project aimed to assess the extent to which each intervention supported children’s acquisition of foundational literacy and numeracy skills.

Community-based learning activities in the intervention villages

- Provided community volunteers and parents with training and materials (e.g. story books and charts) which could be used to support and improve children’s foundational learning.

- Set up children’s reading groups and trained and supported local volunteers to run after-school learning clubs bringing children together from the village.

- Supported local volunteers to organise village events celebrating learning and promoted the idea that children’s learning is everyone’s responsibility, for example through Halla Bol (“make some noise”) activities.

Better accountability through community-school partnerships

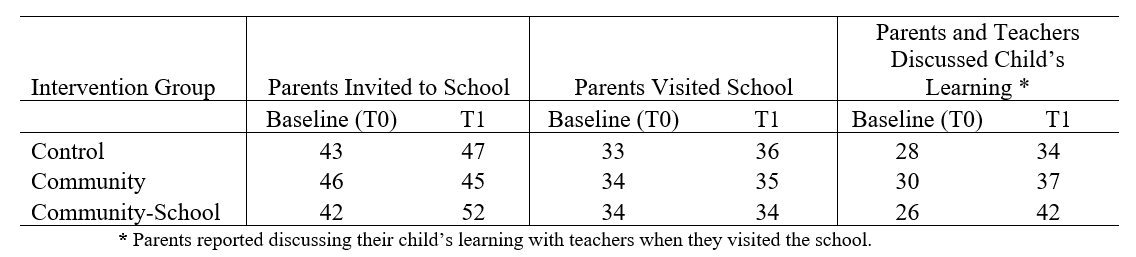

To ensure that communities view children’s learning as everyone’s responsibility, the intervention programme promoted awareness about the importance of learning and ways for better parent-teacher interactions. After the first year of the intervention, we found that more parents had been invited to school (as reported by parents) from the community-school group than the control and community groups, but this did not convert into higher parental visits to school (see Table 1). However, when parents did visit school, the parent-teacher interactions discussing children’s learning increased significantly in the community-school group, compared to other groups.

Table 1: Proportion of parents reporting parent-teacher interaction before (T0) and after Year 1 (T1) of the intervention

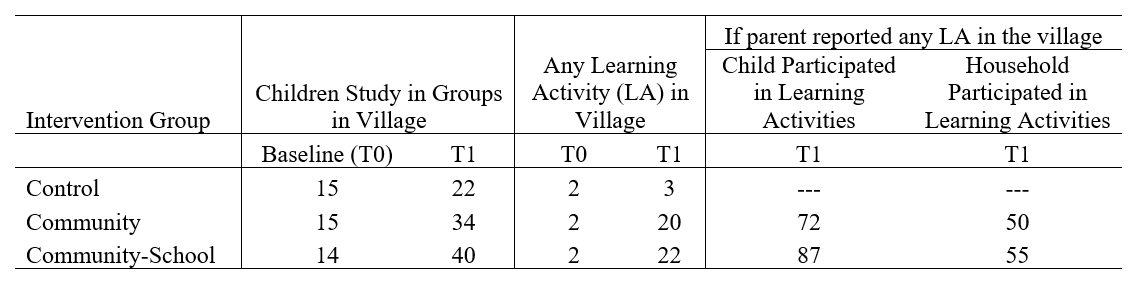

Table 2 shows the change in the proportion of children studying in groups in the village and exposure to any type of learning activities (and participation in them) after a year of the intervention programme. We find that many more children were studying in groups, particularly in the community-school villages. There were many more community-based learning activities in the treatment villages as expected, with the participation rate of children/households higher in the community-school group than community group.

These results show that community-school partnerships significantly increased awareness and parent-teacher interactions regarding children’s learning. More children and households engaged in learning-related activities. Therefore, these findings suggest that the concept of a child’s learning being everyone’s responsibility can be promoted through community-school partnerships, ensuring better social accountability.

Table 2: Proportion of parents reporting exposure to and participation in learning activities in the village before (T0) and after Year 1 (T1) of the intervention

Impact of community-based learning activities on children’s foundational learning

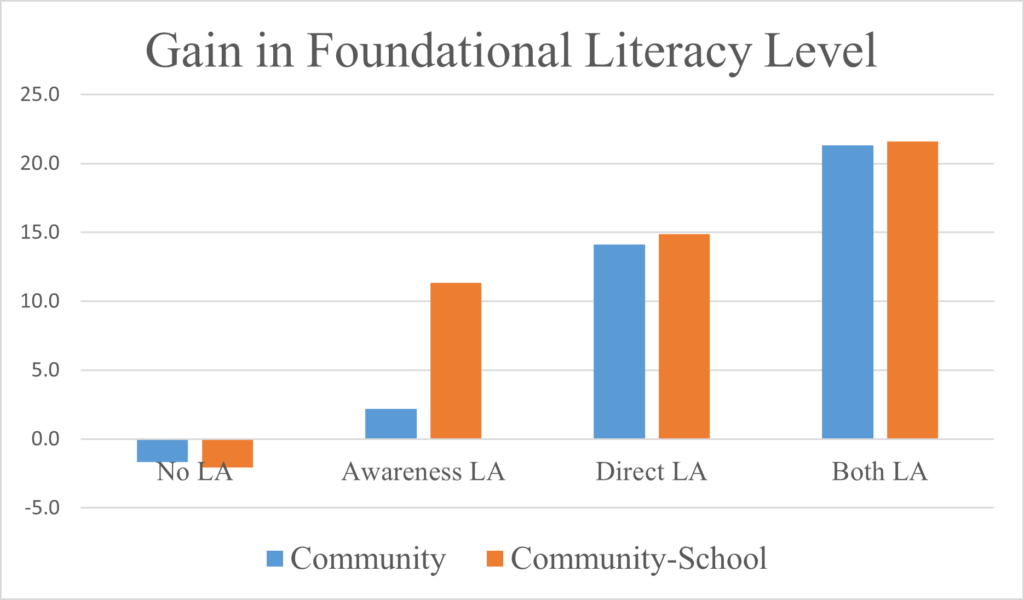

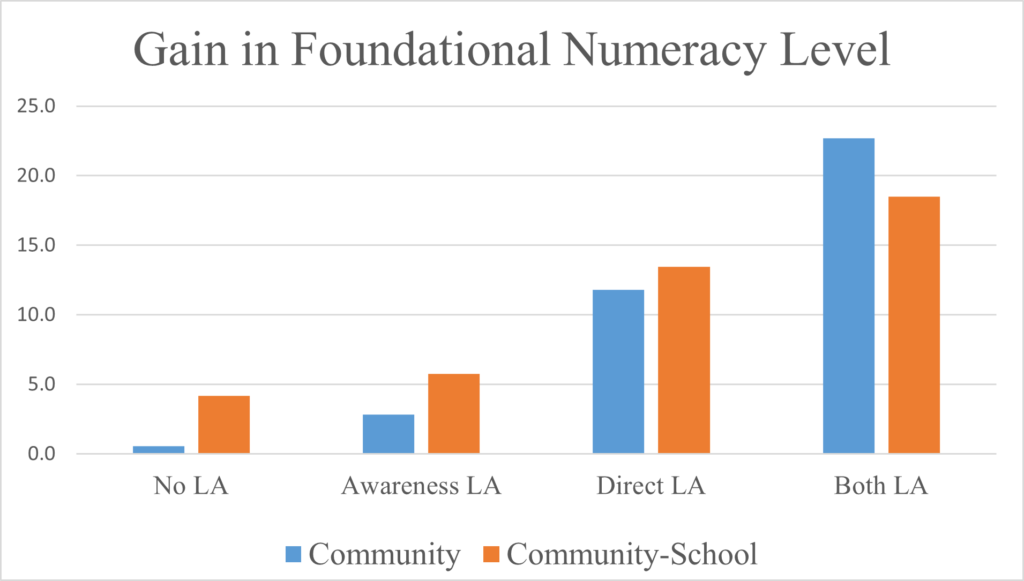

The community-based learning activities described above can be divided into those that aimed to build awareness (Awareness LA) and those that worked directly with children to support their learning (Direct LA). Households could report neither (No LA), either (Awareness LA or Direct LA), or both (Both LA) these types of activities being conducted in their village.

More than two thirds of households (higher in the community-school group) reported being aware of some learning activities done in the village. Compared to the control group (after a year of intervention), Figures 1 and 2 show the gain in children’s foundational literacy and numeracy levels, respectively. Overall, foundational learning gains are significantly higher for intervention group children than children in similar villages who were not part of the intervention programme, and it has a differential effect based on the reported level of programme exposure.

Within treatment villages, foundational learning gains are significantly higher for children who participated in learning activities; those who did not know of or participate in any type of learning activity (No LA) have not benefitted. Moreover, foundational learning gains are highest for children who themselves participated in direct learning activities and whose households knew about the awareness activities (Both LA), followed by those who participated in direct learning activities even though household respondents were unfamiliar with awareness activities (Direct LA). This suggests that awareness-building activities (such as Halla Bol) work as a supplement to direct learning activities in improving children’s foundational learning. Also, these Awareness LA activities are associated with significantly higher gain in children’s literacy levels in the community-school group. This suggests that the community-school partnerships, through better parent-teacher interactions and teachers’ participation in community activities, can have a positive effect on children who did not participate in direct learning activities but whose families were exposed to these awareness-building activities.

Figure 1: Impact of exposure to and participation in community-based learning activities on children’s foundational literacy level.

Figure 2: Impact of exposure to and participation in community-based learning activities on children’s foundational numeracy level.

Conclusion

These findings suggest that communities can play a vital role in mitigating the learning crisis which has marred children’s education. In a country like India, where communities traditionally play many social and economic functions, it is time for them to shoulder one more responsibility: to support children’s foundational learning. Community events such as Halla Bol, aiming to spread the message that child’s learning is everyone’s responsibility, can complement direct community-based learning activities in raising children’s foundational learning outcomes.

In order to fully optimise the potential of the community, there is a particular need to strengthen mechanisms for school-community engagement, recognising that home, school and the broader community are all important sites for children’s learning. This could involve implementing mechanisms for regular communication, coordination and collaboration between teachers, parents and communities around how best to support children’s learning. The Covid-19 pandemic has taught us the value of shared responsibility in protecting the life of the people around us. We should strengthen the notion of schools, communities and families coming together to help children learn.

I enjoyed reading this article. For a very long time I have been thinking that parents and community paly a vital role in child’s education. And school-community partnership can strengthen the role of parents. Would love to know more about this program.

Thank you Mayuri for your comment. I would love to discuss about the program and findings. We can connect through email.