This blog was written by Kath Ford, Young Lives programme and originally published on the Global Education Monitoring Report’s World Education Blog on 18 June 2021.

Substantial progress has been made in educating girls and young women in low- and middle-income countries over the last few decades. The 2020 GEM Gender Report estimated that 180 million more girls have enrolled in primary and secondary education since 1995.

The Young Lives study, which has been following the lives of 12,000 children in Ethiopia, India (Andhra Pradesh and Telangana), Peru and Viet Nam since 2001, has highlighted significant improvement in the educational attainment and performance of both girls and boys compared to their parents, despite the impact of persistent inequalities and gender disparities. Our latest survey, however, adds to the mounting evidence that COVID-19 could not only halt progress but also reverse important gains, hitting those living in poor communities hardest.

New findings from the Listening to Young Lives at Work COVID-19 phone survey shows that while the pandemic has had significant economic and social impacts on adolescent girls and boys, the combined pressures of interrupted education, increased domestic work and widespread stresses on household finances are having a disproportionate impact on girls and young women, particularly those from disadvantaged backgrounds.

Urgent action is required to support vulnerable girls and women to continue their education and avoid long term impacts on their future life chances.

The poorest girls and young women are at greater risk of dropping out of school

Following a lost year of learning, there is a real risk that many poorer students, particularly those from rural backgrounds and without internet access, will be left behind and may never return to education. In Peru, 18% of 19-year-old students in the Young Lives sample had not enrolled to continue their studies by December 2020. Reasons most often given were related to the difficulty in paying fees (as a result of lockdowns), cancelled classes, or a lack of means to attend online lessons.

In Ethiopia, 39% of 19-year-old girls, who were enrolled in education in 2020, had not engaged in any form of learning (including online learning) since school closures began. Even in Viet Nam, where overall internet access is relatively high, students from rural areas were still much less likely to have resumed their classes by December 2020 (63%), compared to their urban counterparts (95%).

Among those most likely to have been disadvantaged by interruptions to their education, it is girls from poor and marginalised communities who have been hardest hit. In India, our results showed a 23 percentage point drop between 2020 enrolment and actual attendance among 18-19 year old girls from Scheduled Tribes and Scheduled Castes, compared to an 11-point drop for boys in this group.

Increasing burdens of domestic work and childcare may reduce girls’ ability to study.

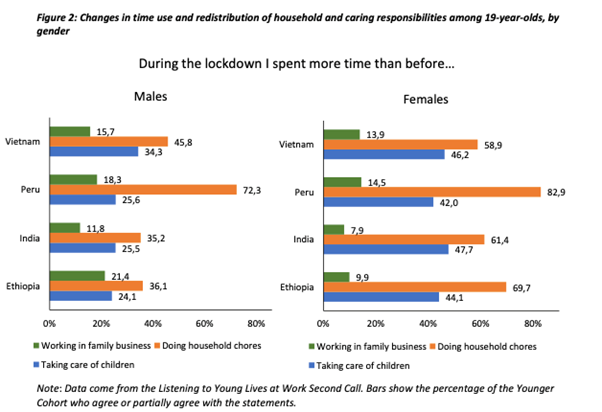

Across all four Young Lives study countries, we find that households tend to resort to traditional gender roles at times of stress, with girls and young women bearing the greatest burden of increased household duties and looking after children. Even where this does not result in dropping out of school, this is likely to significantly reduce the time girls have available to keep up with schoolwork.

In India, 67% of girls spent increased time on childcare during lockdown, compared with only 38% of boys, with similar results found for household work, a factor that previous Young Lives research has found to impact on school attendance. In Ethiopia, 70% of girls spent more time on household work during the pandemic response, compared with only 26% of boys.

Changes in time, use and redistribution of household and caring responsibilities among 19-year-olds, by gender

Girls whose education has been interrupted are particularly at risk of worsening mental health

There are several reasons to be particularly concerned about girls dropping out from school and university following interruptions to their education. While we have seen some improvements, as countries have lifted COVID-19 lockdowns and restrictions, remarkably high rates of anxiety have continued among young people, particularly in Peru, where almost 40% of 19-year-old girls (compared to 32% of 19-year-old boys) reported symptoms associated with at least mild anxiety.

In Ethiopia, 19-year-old girls whose education had been interrupted were nearly three times more likely to experience anxiety and twice as likely to report feelings of depression than those who were not enrolled in education. We found no significant difference between male students and non-students.

Being out of school puts the poorest girls at greater risk of early marriage and parenthood

While we do not yet have specific data on the impact of COVID-19 on rates of early marriage and parenthood across the Young Lives sample, our findings suggest a significant increase in underlying risk factors.

Previous Young Lives evidence demonstrates that girls staying in school is one of the most important factors to reduce early marriage, with schools providing a key platform for advice and counselling. Increasing economic hardship and prevailing discriminatory social norms exacerbated by the pandemic, further increase the risk of vulnerable girls experiencing early marriage and parenthood.

So what can be done?

COVID-19 recovery plans should include adequate education funding to urgently address a lost year of learning, including in higher education, with a specific focus on supporting vulnerable girls and young women. This is particularly critical at a time when significant government spending has understandably been redirected to health priorities.

Supporting disadvantaged girls and young women to stay in education will require a number of targeted measures. Gender sensitive ‘back to school and university’ campaigns should target girls in poor and rural households, including the consideration of cash transfer schemes to reward disadvantaged students where appropriate. Schools and universities need to be effectively supported for the safe reopening and resumption of classes, with efforts to ensure continuing distance learning reaches all students, particularly disadvantaged girls, with extended targeted catch-up programmes and effective teacher training.

Longer-term policies to help address the huge digital divide are required, given the likelihood of continuing online learning, including providing digital devices and internet connectivity in rural areas and for the poorest households.

But to really help vulnerable girls and young women get back to school, we need a range of complementary support programmes responding to specific country contexts. These should include initiatives to help address increasing levels of unpaid housework; adapting social protection programmes to be more shock- and gender-responsive; prioritising urgently needed mental health and psychosocial support for young people; addressing increasing rates of domestic violence; and challenging discriminatory gender stereotypes, which may have been reinforced during the pandemic.

- For more detail see recent Young Lives at Work policy briefs on the impact of COVID-19 on the lives of young people in Ethiopia and India; further briefs from our research in Peru and Vietnam are forthcoming.

- Young Lives is planning to conduct further phone surveys in 2021, with the next regular round of data collection (Round 6) in 2022, depending on the evolution of the COVID-19 pandemic.