This article was written by Rebecca Gordon, Research Fellow in Leadership for Inclusive and Democratic Politics at the University of Birmingham, and Pauline Rose, Director of the REAL Centre at the University of Cambridge. It was originally published on the Developmental Leadership Program website on 28 July 2020.

Image: “we believe that a better world comes from giving better opportunities to women and girls” – Joseline speaks out about girls’ rights in Rwanda at the House of Lords. DFID, Flickr.

Even before the current global pandemic, there was still a long way to go to ensure inclusive and equitable quality education for all: 130 million girls were already denied their right to school and many are not learning the basics. Marginalised girls are likely to be most affected by COVID-19 as a result of school closures affecting the vast majority of countries around the world. Many have raised concerns that these girls will be least likely to return once schools re-open and may have suffered disproportionately from a loss in learning. Yet the barriers to girls’ education are well known, and a growing evidence base shows what works to support girls’ education. There has also been an increase in global political advocacy for girls’ education. Notably, the UK government has committed to supporting 12 years of quality education for all girls, in collaboration with Commonwealth Heads of Government when they met in London in 2018. Given the gap between progress and intention, it is important to consider how political leaders can translate statements into real change for marginalised girls. Our research, which contributed to a report for the Platform for Girls’ Education, focused on this process.

For the UK, this consideration is even more important in the light of the recently announced merger of the UK’s Department for International Development (DFID) and Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO). Given DFID’s long-standing work on girls’ education, it is vital that this expertise is maintained, if commitments to supporting girls’ education are to be realised.

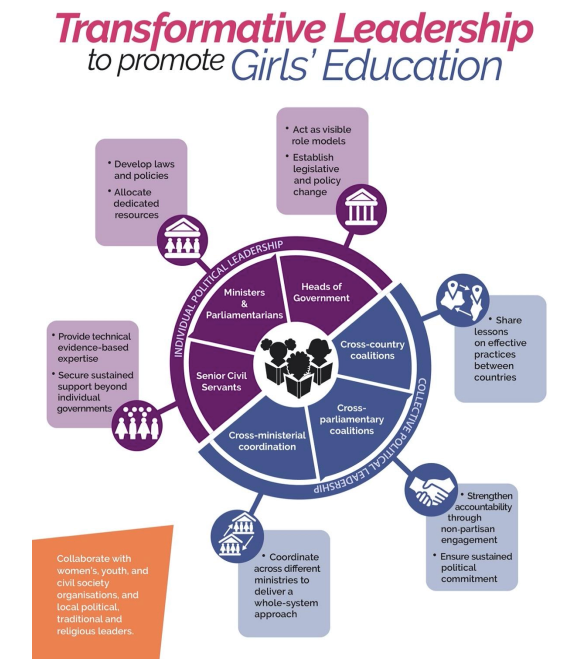

Progress for girls’ education requires action to support gender equality both within and beyond education. Drawing on the work of the Developmental Leadership Program, transformative change requires motivated and committed leaders, who work individually and collectively to convert political commitment into meaningful action. For girls’ education, this social transformation needs to tackle entrenched patriarchal norms and structures that create resistance to change.

Transformative change requires motivated and committed leaders, who work individually and collectively to convert political commitment into meaningful action.

Transformative leadership for girls’ education requires visible and consistent commitment from political leaders on these issues. These leaders must recognise that progress for girls’ education requires a whole-system approach that tackles gender-based discrimination and harmful social norms within and beyond the education system. It requires them to embed gender-responsive approaches in planning and financing across all government departments, which necessitates non-partisan collective action. We outline these issues further through our interviews with eleven current and former political leaders involved in championing girls’ education with respect to who political leaders are, what has motivated their action for girls’ education, and what further action is needed.

Who are the political leaders?

Heads of government play an essential role in advancing gender equality through promoting legislative and policy change. Interviewees further emphasised the need for a collaborative non-partisan approach which includes politicians and civil servants to sustain support and momentum for girls’ education beyond individual governments and electoral cycles: “…You need to look into the actual structure itself and how you can sustain the work that a Minister who has promoted girls’ education did once they leave” (Barbara Chilangwa – Former Permanent Secretary of Education, Zambia).

Achieving reform is rarely an individual action and the involvement of those interviewed in coalitions for girls’ education (notably the Forum for African Women Educationalists) supported their ability to mobilise and to become game changers. These coalitions also enable cross-context learning from successful programmes to challenge gender discrimination in education.

Interviewees also noted that the visibility of women as political leaders has the potential to change the perception of women in society, which could contribute to shifting social norms and so benefit girls’ education. However, we recognise that it is important not to overstate the presence of women leaders in leading to transformative change. According to Florence Malinga (former Commissioner for Planning at the Ministry of Education and Sports in Uganda), it was a woman in the Ministry who had strong objections to letting pregnant girls re-enter education.

What motivates leaders to act?

Interviewees often mentioned how personal experience was an important influence in their commitment to gender equality in education: “a belief in the power of education joined my early feminist beliefs.” (Julia Gillard – 27th Prime Minister of Australia). They also stressed the importance of national political and institutional influences in motivating political leaders to act for girls’ education. For example, global frameworks such as the Convention against Discrimination in Education can exert pressure and hold political leaders accountable.

The central role of data, evidence and campaigns supported by the public was acknowledged as encouraging leaders to make commitments needed to support gender equality in education. For example, Baela Jamil (Chief Executive Idara-e-Taleem-o-Aagahi) emphasised how civil society organisations can incentivise leaders to act by providing information about discrepancies in educational access, through initiatives like the Annual Status of Education Report. This evidence can provide political leaders with direction for policy and reform by presenting both the challenges affecting girls’ access to education and potential solutions. There have also been numerous examples of youth-led initiatives that have motivated political leaders to follow up their commitments to girls’ education with financial resources.

What actions are needed to make progress for girls’ education?

The importance of political leaders engaging with a diverse range of stakeholders, such as women’s organisations, youth-led organisations, civil society organisations as well as local political, traditional and religious leaders were seen to be vital in challenging imbalances in power and disrupting norms that hold women and girls back. This engagement would also ensure the relevance, ownership and effective implementation of strategies to promote girls’ education: “One of the first things my team and I did was to talk to the girls themselves….” (Professor Naana Jane Opoku-Agyemang – Former Minister of Education, Ghana).

These stakeholders also play an important role in putting pressure on leaders to enact legislation, policies and programmes, supporting their effective implementation and holding leaders to account on their commitments to girls’ education.

To develop coherent and coordinated policies for girls’ education, a whole-system approach is needed. Many barriers to girls’ education are influenced by factors outside the education system, such as child labour, early marriage and gender-based violence. “The Minister of Education has to make an effort to coordinate with different departments, such as the women’s department to tackle sexual harassment, gender-based violence… if there is not enough transport, then the Minister for Transport has to be involved” (Genet Zewdie – Former Minister of Education, Ethiopia). Gender mainstreaming in national plans, as well as education sector plans, would ensure that work to progress gender equality in education is cross-cutting and embedded across all government ministries.

There is also the need to prioritise funding for gender equality. Even the best-designed reforms will not be successful unless backed by sufficient resources, appropriately distributed to the groups most in need. The integration of gender equality in funding mechanisms is an important way in which progress on girls’ education can be supported by political leaders.

Wide ranging technical and programmatic expertise on girls’ education can support the above approaches: “We are working closely with DFID, the Department for Education and the FCO… we draw on DFID’s expertise in technical areas, and we use the FCO’s strong experience on the diplomatic side to galvanise support for girls’ education in political multi-lateral situations.” (Senior Civil Servant – UK Government). A holistic approach to promoting gender equality in, and beyond education is essential for sustained progress. Announcing the DFID/FCO merger, the Prime Minister reemphasised the UK’s commitment to ensuring access to 12 years of quality education for all girls. It is of paramount importance that UK leadership prioritises gender equality in their work in the UK, and globally, so that the discrimination that women and girls face in accessing and thriving in education is not intensified and exacerbated.

For a full overview of this work, and acknowledgements to those who supported it, please see the full report.