This blog was written by Rita Locatelli, Post-doctoral Research Fellow at the UNESCO Chair of the Catholic University of Milan and Monica Mincu, Associate Professor of Comparative Education at the University of Turin.*

With almost seven million primary and secondary school students confined at home, Italy was one of the first countries to close schools and is likely to be one of the last to re-open them. This is particularly alarming considering the critical situation which already characterises the Italian educational landscape. According to the latest estimates available, between 2017 and 2018 the percentage of early school leavers increased from 14 to 14.5%, thus interrupting a ten-year trend of slow convergence towards the lowest European average values. Achievement results in the National Assessment Tests (INVALSI) show that territorial gaps are widening, as confirmed by the latest 2018 OECD-PISA results which also indicate that the performance of Italian students is worsening, and is lower than the OECD average. It is generally accepted that the crisis engendered by the COVID-19 pandemic has a significant impact on the most fragile social contexts, intensifying existing inequality and worsening the situation. While notable efforts have been made to ensure the smoothest possible adaptation to distance and online teaching, challenges persist and need to be promptly dealt with.

Teachers are now strongly valued despite non-sufficient investment in their profession

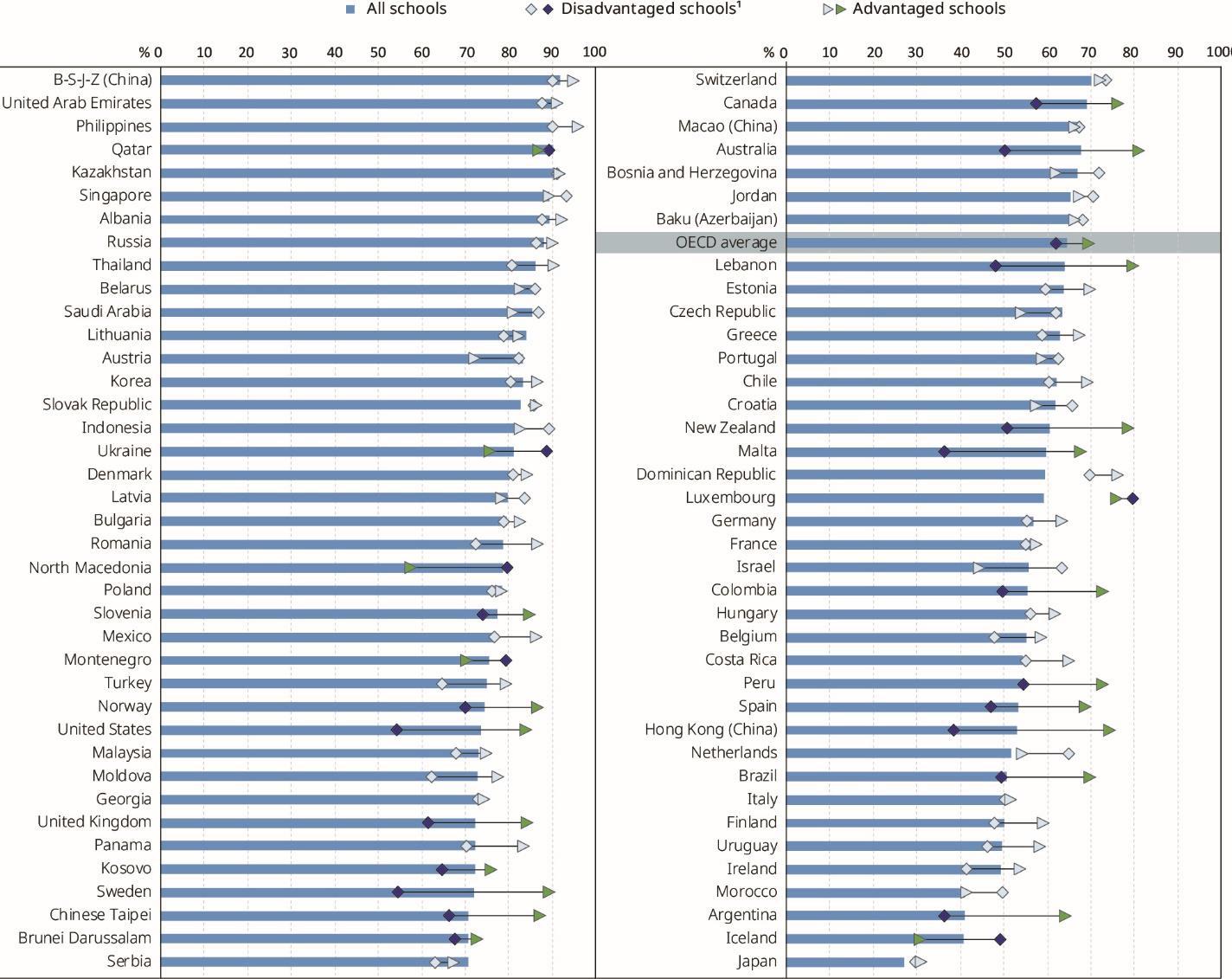

School closure has given rise to an unprecedented, yet necessary, acceleration in the adoption of distance learning solutions. As recently recalled in a blog post published by the UNESCO GEM Report, the introduction of ICT into the Italian education system started in the first decade of the century, followed by the National Plan for School Digitalisation in 2015. By the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, however, only 20% of teachers had attended training courses on digital literacy (Pasta, 2020). According to a recent OECD report, despite professional resources on the use of digital devices being made available to teachers, they had neither the necessary technical and pedagogical skills to integrate such devices into instruction, nor sufficient time to prepare lessons using them.

Source: Figure 4. Teachers have the necessary technical and pedagogical skills to integrate digital devices in instruction. Percentage of students in schools whose principal agreed or strongly agreed that teachers have the necessary technical and pedagogical skills to integrate digital devices in instruction, PISA 2018.

OECD. (2020). Learning remotely when schools close: How well are students and schools prepared? Insights from PISA. Tackling Coronavirus (COVID-19) contributing to a global effort. Paris, OECD, p. 7.

Despite this critical scenario, the great effort made by teachers to adapt to the use of digital devices and overcome this difficult situation is uncontested and has been widely acknowledged by public authorities and by society across the whole country. In a context of general stress and anxiety, teachers are doing their best to help and encourage families in dealing with the various commitments that are being raised during this health and educational emergency. Having said this, the current crisis has raised fundamental issues related to the need to ensure greater investment in the professional development of teachers. While many teachers and school leaders have been able to receive first-hand support on distance teaching thanks to the support provided by INDIRE, the National Institute for Documentation, Innovation and Educational Research, the training they have received to address the current emergency has not been uniform. Moreover, teachers who have not attended university or training courses on ICTs in education may be less willing to move to online teaching. Adequate measures will have to be adopted in order to provide all teachers with the necessary skills to deal with the digital transformation which has been accelerated by this emergency, but whose implications for pedagogy still have to be better investigated and properly addressed.

Distance learning has accelerated the need for rethinking the schooling model and organisation

Despite numerous warnings about the possibility of technology replacing teachers, this emergency has shown that digital devices are merely tools that evolve as history unfolds, but they do not question the very foundations of the learning process, which is based on human relationship and social interconnectedness. Indeed, being at school is also about living together, being connected to one another in a learning community. As also discussed during the first UNESCO Webinar on COVID-19 education response, this forced situation has made it clear that learning goes beyond the confines of the classroom and requires us to reconsider what a learning community is and how relationships and knowledge are created.

As countries rightly try to ensure that #LearningNeverStops through distance education, it is important not to miss this opportunity for a deeper reflection on how to rethink pedagogical practices and objectives. Indeed, new challenges require new solutions, since a mere adaptation of old ways of thinking and of doing is unlikely to produce the required results. Innovative pedagogies that promote trans-disciplinarity, metacognitive skills and critical thinking are necessary in a world where information is increasingly available anywhere and at any time. As such, the mere transposition of the teaching practices adopted in class to online teaching is not sufficient for digital innovation to happen. Some key structural limitations entrenched in the Italian education system, such as non-interactive teaching, summative evaluation and scarce formative assessment, may be exacerbated when using online devices. Moreover, teaching is normally not tailored to the needs of individual students, with just two in ten teachers proposing some forms of differentiated activities for their pupils (Ferrer, 2016[i]; Mincu, 2012[ii]). This critical period may offer an opportunity for favouring an innovation of the schooling model which seems to be ineffective and outdated.

Equity at risk

The technological acceleration that has inevitably come along with the introduction of distance learning solutions has come hand in hand with an exacerbation of social and education inequality. It is calculated that 20% of students do not have access to the Internet at home. The National Institute of Statistics has recently shown that about one third of Italian families has no access to a tablet or a computer at home, a figure which worsens for families living in Southern Italy. The Ministry of Education has so far allocated about 70 million euros for schools to buy digital devices for poorer students and, in collaboration with the public TV service, has launched a series of educational broadcasts for primary and secondary school levels as a measure to compensate the non-availability of digital devices.

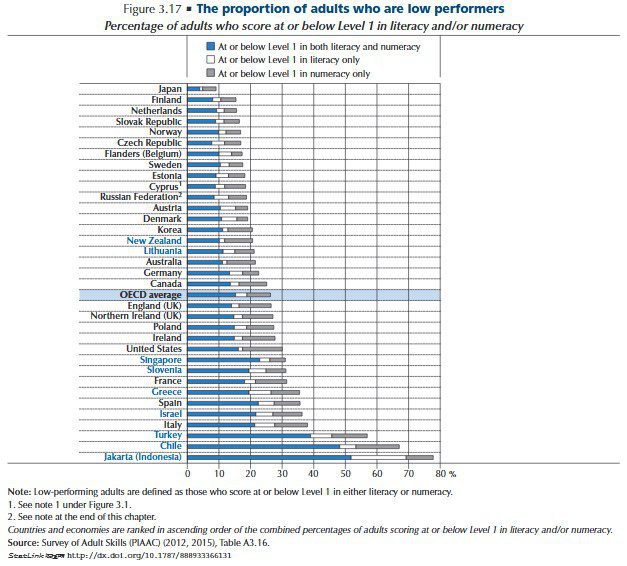

This situation is extremely difficult for students with disabilities and for their families who normally rely on the support of educators and social services which are less available at this time. It is also increasingly evident that children living in families with a higher level of education are better equipped to cope with distance learning, when compared to less educated families. If we consider that the average level of adult skills in Italy is pretty low (OECD, 2019), it is evident that a large number of parents may not have the adequate skills to give their children the necessary educational support.

OECD. (2019). Skills Matter: Further Results from the Survey of Adult Skills. OECD Skills Studies. Paris, OECD, p. 89.

This situation has also engendered new inequalities with regard to the centre-periphery relation, especially regarding students’ wellbeing. Indeed, it is estimated that more than four out of ten children live in conditions of house overcrowding. While students living in cities have usually been at an advantage in terms of better access to educational opportunities, the lockdown has made this situation somehow more tolerable for children living in the country or more provincial areas, where green spaces and larger homes may be more available. The situation in the suburbs, however, remains highly critical due to the concentration of fragile families living in poor conditions.

Governance looking forwards not backwards

As recalled by Armand Doucet and colleagues in their report for Education International, at the onset of an emergency situation, it is necessary to ensure that students, as well as parents and teachers are safe and protected. This approach is well defined by the expression ‘Maslow before Bloom’, which means “safety and survival first before formal education”. Teaching and learning are important but the organisation of distance education must take into consideration the complex and critical situation that students, and teachers themselves, are facing. To ensure that basic needs are met, co-operation among the different sectors of society has to be ensured. School closures may imply the impossibility for students to get access to fundamental social and health services, and this is something that needs to be taken over by society.

A recent article by a group of Italian doctors working at the Papa Giovanni XXIII Hospital in Bergamo suggests that “Western health care systems have been built around the concept of patient-centered care, but an epidemic requires a change of perspective toward a concept of community-centered care.” The authors argue that “this disaster could be averted only by massive deployment of outreach services. Pandemic solutions are required for the entire population, not only for hospitals.” In a similar way, schools cannot represent the only source for education. The responsibility for education belongs to the whole community – from teachers and school principals to educators, home support assistants, but also universities, training centres and cultural venues – and all those involved should be put in the condition to contribute to this shared endeavour (UNESCO, 2015; Locatelli, 2019).

For this to happen, however, effective public governance is essential both during the emergency and for the longer-term perspective. Clear guidelines and planning, as well as strong leadership and vision, are key elements for overcoming the emergency situation and creating the conditions for sustainable long-term solutions. In the initial phases of the emergency, the Ministry of Education reacted promptly with the creation of a dedicated website with useful resources and tools for distance education. However, clear instructions for organising distance education have not been made available and funding for dealing with the current emergency situation and for adapting to what will come next still appear to be insufficient. While teachers and school principals have shown great capacity for organising themselves locally, the central apparatus is showing weakness in making these initiatives become systemic.

In conclusion

There is an urgent need for joint action among the different Ministries and sectors of society. The extension of distance education may create even greater difficulties for families where parents need to go back to work and cannot afford to pay someone to take care of their children who must stay at home because of school closure. This would mean increasing inequality between those who can better cope with an emergency situation and those who cannot.

If public education is to represent the bulwark against inequality, then it is necessary that effective measures are promptly implemented to ensure greater equity in the current emergency situation and a solid and sustainable programming for school reopening and pedagogical innovation for the longer term. The recent establishment by the Ministry of Education of a Committee of Experts is to provide advice to the Ministry about possible innovations of the Italian schools in the context of this crisis and beyond. This can only be done through the implementation of coherent public policies which should reflect a system approach to deal with complex issues.

*The authors can be contacted at rita.locatelli@unicatt.it and monica.mincu@unito.it.

[i] Ferrer-Esteban, G. (2016). Deconstructing the [Italian] black-box. Gli approcci didattici degli insegnanti italiani e le performance degli studenti. Torino, Fondazione Giovanni Agnelli.

[ii] Mincu, M. (2012). Mapping meanings of personalisation. In: Mincu, M. (Ed). Personalising education: theories, politics and cultural contexts. Rotterdam/Boston/Tai Pei: Sense Publishers.