This blog was written by Tim Phillips, Head, Teacher Development, based in Manchester, in the English in Education Systems team of the British Council. He worked as a teacher, teacher trainer and project manager for 15 years in Europe and the Middle East. He currently supports British Council activity globally with ministries of education in developing teacher capacity to teach English as a curriculum subject.

Disruptions to schooling are not uncommon. Earthquakes, floods, epidemics and wars have regularly threatened the education of young people in too many parts of the world. But the global nature of the COVID-19 pandemic is exceptional. And education systems, universally based as they are on a classroom-teaching model, have struggled desperately.

Remote teaching and learning have become key to the response. But what have been the particular concerns of ministries and teachers in providing these? And what positive indications have emerged during the crisis? Two reports of research carried out by the British Council in April and May this year provide insight into these questions, using information derived from 52 school systems and over 9,600 English language teachers and teacher educators in more than 150 different countries. COVID-19 insight reports

A regional snapshot – sub-Saharan Africa

A regional snapshot – sub-Saharan Africa

The reports provide insight into the situation in regions across the world. In sub-Saharan Africa, for example, information from 15 ministries of education was gathered and analysed. The countries are Angola, Botswana, Cote d’Ivoire, Djibouti, Ethiopia, Gabon, Guinea (Conakry), Mozambique, Niger, Nigeria, Rwanda, Senegal, South Africa, Sudan, Zambia. As well as this, 546 teachers and teacher educators in 29 countries in the region completed an online survey.

Among the variety of responses from ministries in these African countries related to organising alternatives to school-based instruction, on the positive side, there are innovations. For example, in Senegal, the Ministry of Education distributes printed copies of online resources through regional bureaus around the country. In this way learners with challenges accessing the Ministry’s website can take copies home to study from.

Interestingly, as many as 45% of all the teachers surveyed in the region say they are teaching synchronously (higher than average across all respondents globally) and 81% asynchronously, with over 70% rating their confidence highly in remote teaching and training. Accepting the caveat that only those teachers with access to the internet would respond to an online survey, this finding is still a positive indication from teachers.

Comments from teachers and teacher educators indicate their insight into how remote teaching and learning can work in the local context. One teacher educator wants “recordings to be sent to teachers with solar energy devices as many areas may have electricity problems”. Another wants to know “how to use WhatsApp for online teaching and assessment”. Another asks for “new simple applications for smartphones, simple lessons, practical worksheets in grammar, vocabulary, pronunciation, useful games…”

Overall the picture that emerges is one of challenge, but considerable commitment and ingenuity in finding ways to continue education through the pandemic.

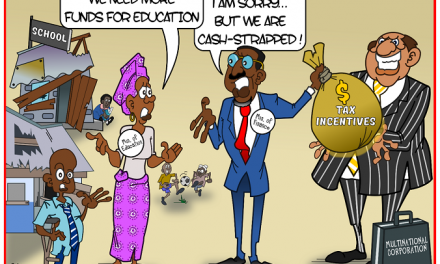

Global insights

Equity and access are the most frequently reported challenges cited by both ministries of education and teachers in the research globally, with teachers commenting on the realities they face. One teacher comments, “My learners come from a poor, rural area. They mostly live with the grannies, and do not have access to internet. About 30% also do not have access to WhatsApp. The caregivers complain that they cannot get them to sit down and work or read.” Another confirms how COVID-19 reinforces existing inequalities:” I fear for the low income, low technology groups. They miss out again.”

The support for teachers to teach remotely is also a common concern. As one teacher says, “My main problem is having the time to learn all of this! We went straight into online classes and I felt like I was treading water to just keep on top of planning and delivering classes as well as correcting homework submitted by e-mail.” Yet, although over 70% of education ministries stated they were providing support for teachers to teach remotely, ministries have found it challenging to introduce teacher support systems to facilitate large-scale remote teaching, especially as internet access is a common issue. The reports find that only a third of the education systems reviewed provide synchronous teaching of subjects, yet 88% of them support remote learning through TV, radio and print, therefore teacher support seems critical to maintaining standards of instruction and learning.

Forward thinking

For teachers and teacher educators, the crisis has represented a challenge to the skills and expertise they need in the 21st century. What educational technology should an education system be resourced with to provide an inclusive education that is fit for a technological age and can respond to further crises like the COVID-19 pandemic? A part of the answer to that question is to understand the experiences of teachers during the crisis – to recognise their resilience and agency, and to learn from the teaching methods they have tried and the obstacles they have faced. There may be some hope that out of the severe challenges of the COVID-19 disruption, a new understanding could revitalise education for all.

References:

British Council reports: “A global snapshot of Ministries of Education responses in the state primary and secondary sector” and “A survey of teacher and teacher educator needs during the Covid-19 pandemic April – May 2020”

Thank you British Council for the brilliant article