This article was written by Rammohan Khanapurkar, a public policy researcher with an MA in Education and International Development from UCL; Ketan Dandare and Shalini Bhorkar, PhD candidates at the UCL Institute of Education. Here, they evaluate an online teachers’ development programme conducted from a remote village targeting rural teachers during the coronavirus lockdown in India. This article was originally published on The Quint on 15th July 2020 and explains the unique approach of this programme and how it prepared the teachers to address the ‘learning lag’ of students due to the lockdown.

Equipping teachers to recognise where to start post-lockdown is as imperative as steps to give online education – the case of Maharashtra State, India.

As the Covid-19 crisis saw the world lurched into lockdown, digital education finally got its place in the sun around the world. The sudden gush of digital education and the rush to offer online education brought the much-debated fault-line of digital haves and have-nots to the fore. The mainstream discourse around the challenges of digital education was based mainly on infrastructural inadequacies of students, especially in the rural regions. In Maharashtra, surveys like the Active Teachers’ Forum highlighted the absence of smartphones and patchy connectivity in rural regions. This also implies that a vast majority of children in the government school are likely to suffer from a short-term learning loss due to absence of online academic support. If not addressed appropriately, then this loss can be detrimental for children’s progressive learning curve once the school reopens. Equipping teachers to recognise where to start post-lockdown is as imperative as taking hurried steps to give online education. Both these objectives can be mutually inclusive if there is a strategy to realise it.

The effects of the pandemic faced by teachers’ communities are much deeper than any other situation they previously encountered in their service. The sudden quietude teachers faced due to an abrupt halt and uncertainty in education is also something they have never experienced before. Apps like DIKSHA, NISHTHA and ePathshala by the Ministry of Human Resource Development’s (MHRD) Central Institute of Educational Technology aimed to provide teachers with a plethora of training opportunities during the lockdown.

While these e-resources are available to teachers, the onus of critiquing, filtering and using them, lies entirely on their motivations. As such, existing online resources do not adequately prepare teachers to deal with bridging the learning lag of students due to lockdown. Children with fluent access to digital resources and active involvement of parents in learning can study in a ‘virtual school’ in an unhindered manner. However, many children are still first-generation school-goers in various parts of rural areas and in the low-income groups in cities. The impact of several factors, such as missed school time, knowledge regression and stress resulting from lockdown on these children need a humane consideration when school reopens.

The most precious resource of “time” is now available at the teacher’s disposal. Even with limited connectivity, they can use Whatsapp chats and video calls using smartphones. The state government of Maharashtra has not been oblivious to this reality. Along with the educational content, it resorted to organising webinars on non-teaching subjects. These webinars gave teachers an opportunity to listen to and interact with renowned personalities from both educational (Manish Sisodia, Raghunath Mashelkar) and wider (Sports persons, Virdhawal Khade and Tejaswini Sawant, actor Sonali Kulkarni) spheres. Still, the moot question remains, ‘is this good enough?’

The situation also requires tailormade online courses for targeted knowledge enhancement and skill reinforcement of teachers. They must act as “bridge programmes” for armouring teachers with instructional skills to address the socio-emotional and learning needs of children post the pandemic. While this comes across as a tall order, it is doable as seen in experiments conducted by some non-state organisations during the lockdown period. The state government can draw wider learnings from these experiments to use online education for more focused tasks than just occupying teachers.

Non-state entities, especially the not-for-profit organisations, have played a significant role in providing a knowledge-curve to the government on various teaching-learning matters. The Government Resolution of Pragat Shaikshanik Maharashtra (Progressive Education in Maharashtra) in 2015, even encourages the teachers to use e-resources of certain not-for-profit organisations. The list mentions Quality Education Support Trust (QUEST), which primarily works to enhance teaching quality of government school teachers. QUEST has a large repository of content on language and Maths which is developed with an eye on research and contextualised as per the rural classroom realities. The content is available in the public domain under the creative common license.

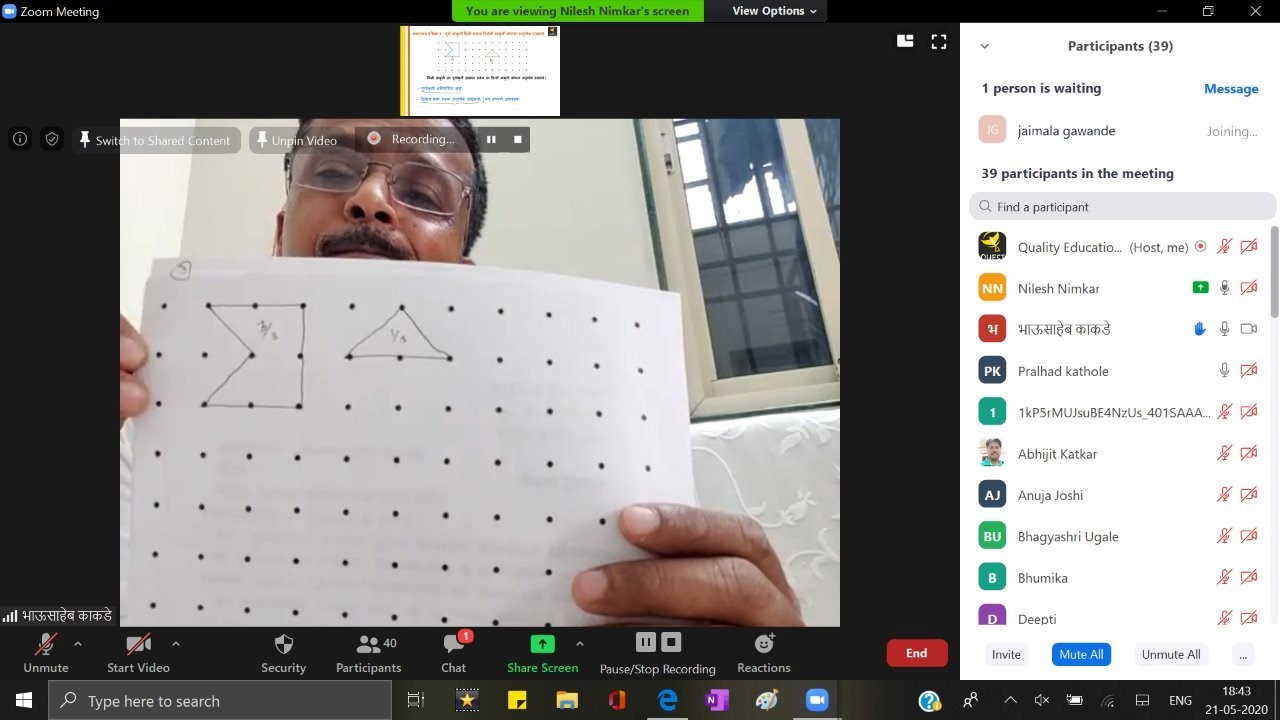

When the lockdown began and the reality of real-life classrooms appeared a distant reality, QUEST focussed on teachers’ development with a ‘flipped classroom’ instructional strategy. This strategy involved both synchronous and asynchronous components. The asynchronous part involved pre-session readings and analysing video content before the actual online sessions. The synchronous part was the actual online interactive workshop fostering dynamic group interactions. While providing teachers their first-ever immersion into a flipped classroom setting, this strategy also supported the differentiated learning abilities of teacher participants. This approach gave QUEST latitude to address the issue of students’ learning lag and identify ways to deal with it during the flow of discussions with teachers. Content related to the following day’s session was sent to teachers who joined Zoom sessions from far-flung locations of Maharashtra.

It included academic articles translated in an easily understandable language, concrete examples of children’s works and classroom instructional videos. The quantity was also just appropriate so as not to overwhelm the participating teachers but rather to create a reflective space. The daily synchronous sessions were interactive as the course conductor used previously sent materials to initiate and moderate robust discussions among the teachers, who then interwove these insights with their personal classroom experiences. Most of the teachers joined zoom calls using mobile internet packs which curbed flowing video interactions. QUEST filled this gap by showing thematic presentations and generating vibrant voice-based discussion around it. When any teacher got disconnected due to connectivity issues, they would immediately send messages on Whatsapp and share their views.

This zest to stay ‘connected’ and the spirit of learning surmounted technological odds. The discussion on Whatsapp would continue long after the online sessions ended. The online chat messages would organically move to the next session as the resources for the following day’s lesson got uploaded on Whatsapp group. It was observed that the participating teachers would continue their discussions and learning even after the end of a week-long course by forming a social media-based community.

Prima facie, this approach appears doable and offers rich insights to the state to address the key issue of the learning lag of children, and teachers’ capacity building for the same. Use of popular and user-friendly platforms like Zoom and Whatsapp make it a breezy affair on the technological side. Yet, there is an expertise and perspicacity involved in curating the right content and manoeuvring the sessions in such a way that all teachers find it participatory and inclusive. It also aligns with the instructional know-how of teachers with an appreciation of their social and cultural surroundings.

Reaching a larger teacher force with such similar programmes will help further the state’s digital push. At the same time, it will prepare the teachers with specific skills and knowledge to face the new post-pandemic reality once the schools resume. It will also boost teachers’ confidence to help under-served students’ population in bridging the lockdown induced learning gap. Thus, shifting the current focus of online education on empowering teachers will yield rich dividends in the long run.