This blog was written by Rabea Malik, Assistant Professor at the School of Education, Lahore University of Management Sciences (LUMS) and Research Fellow at the Institute of Development and Economic Alternatives (IDEAS) in Pakistan. This blog is part of a series from the REAL Centre reflecting on the impacts of the current COVID-19 pandemic on research work on international education and development.

The role of governments is key in mitigating the disruptive impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on education delivery and outcomes. Effective response guidelines for governments stress the need to plan for long-term disruptions and strategic adaptation, and to coordinate, communicate with and support the education workforce, including and especially the head teachers and teachers. Much like the health response to the pandemic, an effective education response requires planning for phases. At the onset of the emergency, most countries mounted a rapid response by leveraging technology to start home-schooling mechanisms that can help cope with lost instructional time. The second phase requires policy planning for managing continuity of instruction when schools reopen, including ensuring children return to schools, instruction takes account of potential learning losses during time away from schools, and teachers and school leaders are fully supported as they work to realise these goals.

In this blog I consider what these guidelines mean for Pakistan’s large, diverse, federated education system. I argue that given the scale of operations and the nature of entrenched inequities, the key guiding principles should be to address inequalities and to strengthen decentralised governance and service delivery. Existing data, vulnerability assessments and rapid evaluations can help inform policy for more effective COVID-19 response.

Multidimensional inequalities define the shape of the challenges faced by education systems today

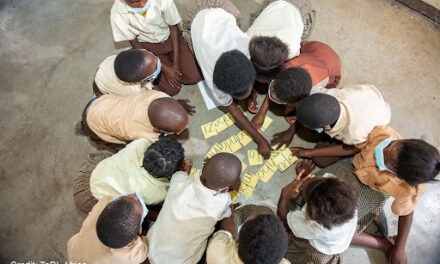

As a result of global school closures, it has become immediately clear that the children at risk of dropping out and those who are likely to experience the most significant learning losses are the ones from marginalised backgrounds. Poverty, gender and location are intersecting to entrench exclusion for already-marginalised children. Existing data sources help establish the scale and scope of the challenge.

Federal and provincial governments in Pakistan have moved quickly to start airing curricular content for K-12 via television channels. This is the correct strategy, given televisions are much more widely owned than radios: according to DHS 2017, 62.5% of the sampled households had a TV compared with 11% who own a radio. However, these averages hide stark inequalities. For example, in Punjab children in households in the poorest homes (only 17% of whom have TVs in their homes) are much less likely to be able to benefit from this policy initiative than children in the richest households (95% of whom have access to television). The numbers for Sindh are similar: 96% of households in the top quartile have televisions, 20% in the bottom quartile have televisions.

Accessing these opportunities and initiatives becomes more complex and unequal if priced technologies such as cable channels or internet and smart phones are used: Less than 1% of the poorest households sampled for Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys (MICS) 2017 owned a computer, and while 82% of them owned a cell phone, only 4% had access to internet. District officials in Punjab share that internet and cable infrastructure is common and reliable in urban areas. Children further away from cities are much less likely to have access to instructional content sent through smart phones and aired on cable channels. Officials distinguish between parents who own smart phones and those who do not, a divide that is significant because many government school teachers in Punjab are relying on WhatsApp for communicating with parents. Parental occupations directly impact the opportunities children can take advantage of; during the crop-cutting season, many in rural areas are likely to be helping their parents harvest crops

The gendered experience of exclusion from access to technology and the increased burden of care on girls is a key dimension of inequality during this disruption. A recent blog about access to digital learning demonstrates that girls are much less likely to have regular access to any form of technology. Inequalities in access worsen for girls in rural areas and those in the poorest households. The increased burden of care in the households during the pandemic is much more likely to have hit girls the hardest, making it much more likely that they are effectively excluded from accessing COVID-response measures around education. Globally, women and girls carry out three times the amount of unpaid care and domestic work than men and boys, and this load is likely to have increased during periods of school closures and lockdowns. As COVID-associated health and economic shocks threaten to push millions into extreme poverty, girls are more at risk of dropping out of schools.

Learning losses are likely to be unequal also

Being in school matters for learning. Research on teaching and learning in government schools in rural Pakistan shows 10% learning gains after a year of regular schooling for children in grades 3, 4 and 5. These gains are threatened by school closures for reasons listed above.

The World Bank has outlined three scenarios of learning losses that governments should prepare for when schools reopen:

- there is a loss of learning for all students due to school disruptions;

- the lowest performing children fall further behind while the well-performing children move ahead – this is predicted based on the ability of the families to support children in keeping up with reading and writing and access to assets such as televisions and a good internet or cable connection;

- there is a sudden and large increase in numbers of children for whom learning falls because of an increase in numbers of drop outs.

Government schools in Pakistan are likely to find themselves facing the second or the third scenario. Furthermore, provinces stand at various levels of capability for testing and also delivering learning gains. Pre-pandemic learning data show much less variation in children’s ability to read in local languages in the early grades across provinces (between 72 and 80% in grade 1 were able read letters); there is much higher variation in skills in higher grades (68% children in rural Punjab could read a story in local language, while only 40% in Sindh could do so) (ASER, 2018). This is true for Maths and English literacy as well.

It will be imperative to assess children when they return to school to establish learning losses, which are likely to vary for children given differential access to home support, technologies and differential exposure to health and economic shocks.

Medium to long term continuity will need to account for inequalities

Ensuring that policy responses address inequalities requires systems that can: mobilise quickly to collect information about the situation of teachers, schools, students and communities; repurpose their workforce to support new goals for coping in the crisis and managing continuity; plan for changes in instructional calendars and goals; make space for experimenting with new techniques that have proven to be effective for improving teaching and learning.

Data for identifying at-risk children

Strengthening of data systems has been one of the key areas of progress in education system development in Pakistan over the past couple of decades. All four provinces in Pakistan have well-functioning Management Information Systems (MIS) that collect data on operations of schools on a regular basis. These systems can be quickly repurposed for planning for COVID response. Tangibly, this requires individual and community level information about children who are more at risk of dropping out, those who aren’t able to access home schooling measures/technology, who are in households that have experienced health and/or economic shocks during this emergency. Given the proximity between schools and homes, teachers and head teachers are best placed to provide this information. District officials in Pakistan are confident that teachers and head teachers have (or can quickly gather) information needed for identifying different cohorts of children.

Plan for strategies for resumption of attendance and reduction of drop-outs of the most at-risk

All four provinces in Pakistan have girls’ stipend programmes in place for maintaining enrolments through high schools. These may need to be expanded and the stipend raised (even if as a one-time measure) to increase the likelihood of girls returning to schools.

Education departments routinely rely on teachers to run door-to-door campaigns for school enrollment and for improving attendance at the start of a school year. However, placing the entire burden of the task on teachers and school leaders detracts from their instructional responsibilities. Given the scale and scope of disruption, teachers and school leaders must be supported by running a dedicated, large-scale coordinated, public awareness campaign when schools reopen after the COVID closures. This can be combined with targeted text messaging and personalised visits for children who are living in localities or households identified as high-risk.

Small scale rapid evaluations of various measures as they are implemented can help assess impact and correct course.

Plan for assessing children to inform remedial and differentiated teaching strategies

The past decade has seen investments in building capacities for generating learning data in classrooms in at least three provinces. These foundations can be used to generate sample-based assessments for system-level diagnostics, combined with best practices in formative assessments that can help teachers direct instruction at an individual level.

Provincial education departments are working on readjustment of curricular goals for the year to make them more realistic, with advice from subject experts. Remedial instruction strategies, proven to be effective, can be combined with rationalised goals to ensure all children, particularly those excluded from instructional support during school closures, are able to catch up. Finally, this emergency presents an opportunity to test strategies that allow teaching children at the right level, rather than prescribed student learning objectives (SLOs).

It is imperative to incorporate the experience and voices of teachers in planning for instructional continuity. Chronic shortages in the system means teachers in government schools across provinces in Pakistan acquire experience and skills on the job for teaching multi-grade classrooms. These skills may offer a foundational concept that can be built on to equip teachers with effective strategies for teaching differential ability students in the same classroom.

Decentralised systems are likely to be more effective and resilient in responding to disruptions

Achieving the tasks set out above require very large education systems to be able to plan, repurpose and implement fairly quickly. It becomes clear in conversations with various stakeholders involved with government response to COVID-19 that provinces will be benefiting now from reform efforts undertaken in the past couple of decades. Effective response to emergencies is contingent on repurposing of existing structures that reach schools, teachers and communities, and are responsive to local contexts and problems. In so far as this is true, decentralised structures are better primed for the job. At the provincial and district level, this requires:

- capacity for data collection and utilisation (including data on at-risk children, teaching and learning);

- staffed structures in place that link higher tiers of governance with small clusters of schools;

- capacity to deliver on-site, continuous teacher training and support programs;

- flexible financing for schools.

Punjab and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) have made the most progress so far on reducing teacher shortages, building system infrastructure for on-site teacher training, putting in place the human resource and technical capacity of education departments at the district level to support teachers and head teachers, collecting teaching and learning data and utilising data for policy planning, and making financing available to schools. Punjab and KP have added this depth to their district level delivery and governance structures over the past decade: the tier of Assistant Education Officers (AEOs) in both provinces are managing between 10 and 40 schools. In Sindh in contrast, Talukka officers are managing up to 100 schools. Sindh and Balochistan may need to invest simultaneously in building these systems while planning for coping and continuance strategies. All provinces will need to empower teachers and head teachers as key actors in their response plans.

Real-time systems level analysis of structures and functions, as well as qualitative documentation of management and response practices at various hierarchical levels and across provincial contexts can potentially generate important insights about delivery and governance mechanisms that make education systems more resilient to crises.

Hi,

I am from US and have been affiliated with a small Facebook channel in Russia. We are investigating covid’s effects on Pakistani education. Is it possible to interview you on Facebook. You can contact me on my email.

Kindly let me know. Thanks

Rabia

Hello Rabia

I have forwarded your message to Rabia M.

Hello recently i got a task on challenges and difficulties facing by students. and i am working on that.

Hello,

I am Kamran from Pakistan I working on my assignment

”How is Covid-19 changing education system of the world and especially the higher

education system? Take a stock of all universities in Pakistan in terms of faculty,

students, programs, and facilities. Are our universities ready for online dissemination of

knowledge? Present latest facts and figures in your presentation”

If you have any related data please send me on my email

kAmranburhan09@gmail.com

AOA if u want any related help about education sector i m ready

Covid 19 damages our education and jobs system specially when bise lahore board is not sure and decide about the exams date for the students, but lots of people got the opportunity in tech industries and getting so much response in the world wide.

This is saddening to read and see. I really hope that the situation there for the students would get better for every child deserves the right to an education.

Here you share your best knowledge with us. I highly appreciate your work.

click here

click here