This article was written by Education Development Trust, who, like other organisations in the sector, we have been pivoting their programmes and research in response to COVID-19 and developing an evidence base on ‘what works’ in education in emergencies and remote education. From this, they have developed new thinking, ‘Learning Renewed’, which presents practical approaches to help system leaders re-open systems to tackle the emerging learning crisis, whilst considering what more effective, equitable and resilient education systems might look like moving forwards. ‘Learning Renewed: A safe way to reopen schools in the Global South’ is their first major think piece in this series. It outlines a vision for the ‘flexible reopening’ of schools, supplemented by community-based learning – which could offer real potential to ensure higher quality education provision for some of the world’s most vulnerable children.

As education systems around the world begin to emerge from Covid-19-related lockdown, governments are facing the difficult decision of when and how to reopen schools, balancing the risks of widespread learning loss – and the impact this will have on a generation of learners – with the risks of virus transmission, which are more significant in low-income settings. In this report, we propose a middle way between full closure and reopening, which would not only enable schools to reopen more safely, but also holds real potential to improve learning outcomes for some of the world’s most vulnerable children.

Throughout Covid-19 pandemic, Education Development Trust has sought to be highly responsive to the changing needs of educators, system leaders and our partners around the world. In doing so, we have developed an evidence base from which we have developed new thinking, which we call ‘Learning Renewed’, which reimagines what more effective, equitable and resilient education systems might look like, and how they might better withstand future shocks. This programme of work will be continuing in the coming months, but here we present our first major think piece in this series, ‘Learning Renewed: A safe way to reopen schools in the Global South’. In it, we outline our vision for ‘flexible reopening’ of schools, supplemented by community-based learning.

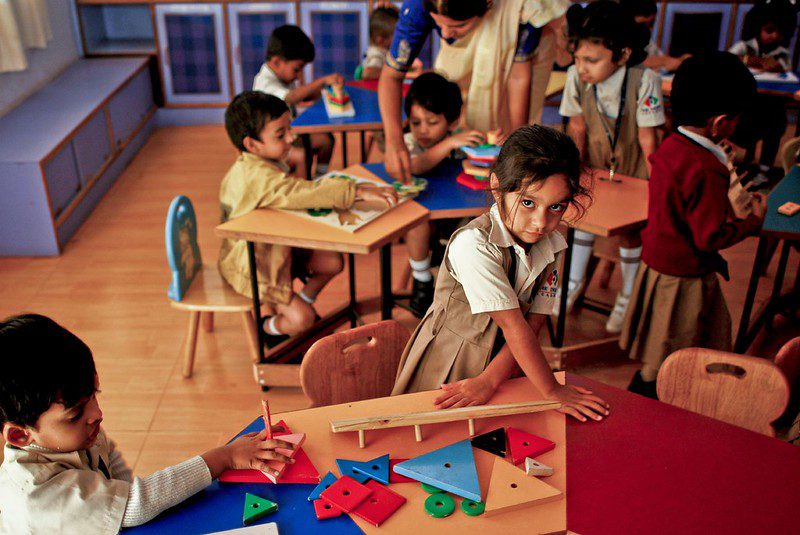

Such new thinking is necessary – not only due to the epidemiological risk of Covid-19 transmission, which is heightened in low-income contexts by large class sizes, poor sanitation and high levels of inter-generational households, but also because a return to ‘normal’ will fail to solve the learning crisis that existed even before the pandemic. Partly due to large class sizes and lecture-style pedagogies, many children in low-income countries complete primary education lacking even basic reading, writing and arithmetic skills. We must therefore consider not only how to reopen schools, but how to improve learning outcomes for the children who attend them.

We therefore propose a ‘middle way’ between full closure and full reopening, featuring smaller, tutorial-style classes attending school on a part-time basis, supplemented by community-based learning. This responds to a clear and urgent need to reduce class sizes – enabling social distancing and helping to ensure that pupils receive more direct feedback and guidance than would be possible in the large, overcrowded classrooms that are common in low-income contexts. Moreover, given that many students will lack a suitable environment, literate family member, or access to technology to support their learning at home, we advocate the use of non-formal learning opportunities at the community level, supported by a literate facilitator, to supplement formal schooling.

There are of course key conditions of success for such a model, not least adequate professional and pedagogical training for teachers, facilitators and school leaders, and ensuring parental buy-in. The use of technology should also be carefully considered and integrated into community-level learning in a way that is pedagogically helpful and context-appropriate, and centralised teaching resources will need to be developed to reduce burdens on teaching staff. Crucially, the quality of provision also needs to be ensured, and disaggregated data will be fundamentally important for identifying and tracking the engagement of vulnerable groups of students.

The model we propose is not without challenges, but we believe that it offers real potential to ensure higher quality education provision for some of the world’s most disadvantaged children.