This blog was written by Dr. Yahia Baiza, Research Associate, The Institute of Ismaili Studies in the UK.

Afghanistan’s Ministry of Education (MoE) faces the mammoth task of delivering education to over 9 million learners during the COVID-19 school closures. To control and reduce the spread of the virus, the MoE, in consultation with the government, decided not to start the new school year on the 23rd of March 2020. The government also decided to close all public and private institutions of higher education. The initial closures were for over a month (14 March-17 April), which were then extended for one more month until the end of May, which also coincided with the month of Ramadan (Muslim’s holy month of fasting, 23 April -23 May 2020).

A schoolgirl watches an educational programme on television in Herat city, 12 April 2020. Credit: Salaam Times.

The MoE was quick to adopt new approaches, supported by its national and international partners, to mitigate the impact of COVID-19 on the education system. Under the slogan of ‘education continues’, the MoE has decided to deliver education through two options:

- Distance learning via the internet (digital) and radio and television broadcasting; and

- Learning at schools in smaller groups under the health guidelines of the Ministry of Public Health.

- Distance learning

Distance education in Afghanistan, like in all other countries around the world, has its benefits as well as challenges. The obvious benefit is to make educational materials available via the internet, and radio and television broadcasting to students who, due to the school closure and quarantine measures, do not have access to schools and daily classroom activities.

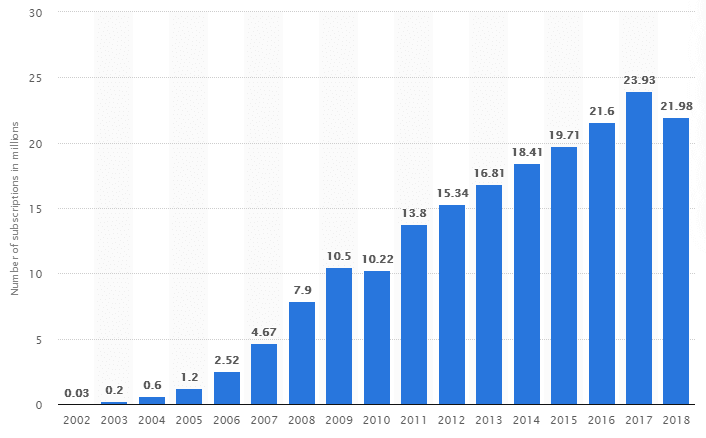

In Afghanistan, the telecommunications sector has been growing at an encouraging speed. As shown in Figure 1, the sector virtually grew from nothing in 2001 to over 21 million subscribers in 2018. Although there is a 2% fall in the number of subscribers from 2017 to 2018, the Afghanistan Telecommunication Regulatory Authority (ATRA), which regulates the country’s telecommunication sector, reports that the subscription rate spikes again to over 22 million in the fourth quarter of 2019. Of this, as BuddeComm reports, 92% of the subscribers are pre-paid and the remaining 8% are post-paid users. The telecommunications network now covers over 90% of the population, which is a major achievement.

Figure 1: Number of mobile cellular subscriptions in Afghanistan from 2002 to 2018 (in millions). Source: Statista 2020.

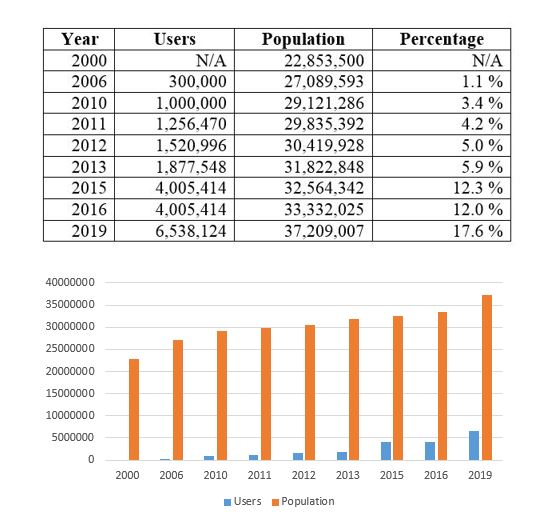

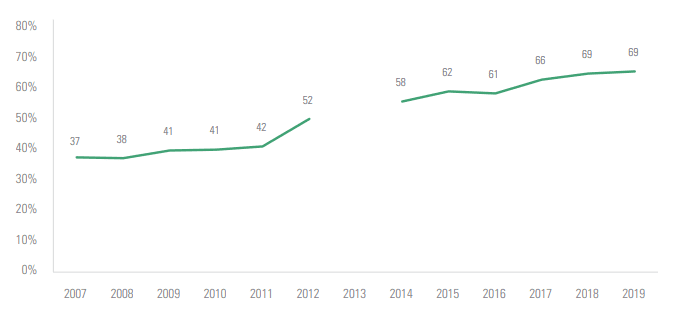

There is a similar visible increase in the number of internet users. As shown in Figures 2 and 3, internet usage has increased from nothing in 2000 to over 6.5 million in 2019. The two figures also show a 16-fold increase in the number of internet users from 2016 to 2019. Of this, 633,050 are 4G Broadband users, and the remaining majority are 3G Broadband users. The mobile as well as the internet sectors are still at an early stage of their development. It is predicted that mobile broadband penetration could reach 35% by 2024, with a subscriber base of 14.8 million.

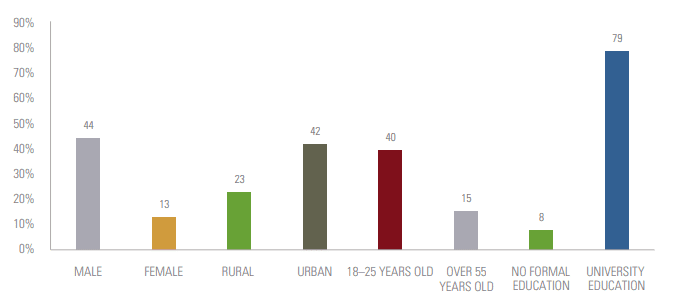

In terms of personal access to the internet, Figure 4 shows significant differences by gender, geography, age and education. Men have more access (44%) to the internet compared to women (13%). There is also a clear disparity between urban (44%) and rural (23%) areas. Age group also makes a visible difference in personal access to the internet, as the younger population (age 18-25) is the highest internet user. University students and graduates (79%), the majority of whom are male urbanites, have the highest rate of personal access to the internet.

The availability of electricity makes a significant impact on the population’s access to television and radio in Afghanistan. According to The Asia Foundation’s 2019 report, A Survey of the Afghan People in 2019 (Figure 5), ownership of television is more common among urbanites (91.1%) than in rural areas (62%). The Survey also suggests that listening to radio continues to be more prevalent in rural areas (62.4%) than urban areas (42.2%), where residents generally have less access to TV and the internet. Likely, the urban-rural gap will further decrease over the coming years as various national and international energy projects will make electricity more widely available across rural areas.

Despite the obvious benefit of distance education, which is primarily dependent on the availability and affordability of modern information and communication technology, teachers and textbooks are the cornerstones of all national curriculum around the world. However, teachers’ approaches to the use of textbooks in delivering national curriculum differ from country to country. In the UK, the use of textbooks in schools has declined over the past decade. In England, only 10% of maths teachers use textbooks as the basis for their teaching, compared to 95% in Finland and 70% in Singapore. In Afghanistan, the national curriculum is solely delivered through a single set of textbooks for each grade across all public and private schools. In situations of emergency, the MoE have the advantage of existing content for developing recorded audio and video lessons and delivering them via radio and television and the internet all across the country.

Over the past two months, the MoE recorded hundreds of hours of audio and video-based content for general education (grades 1-12) and three levels for the adult literacy programme. These materials have been made digitally available via the internet at the Ministry’s website and are freely accessible to all learners, as well as through radio and television broadcasting, using national channels and local private broadcasting channels. The recorded content follows the national curriculum and is based on individual school textbooks for each grade, teacher guidebooks, and the lesson number and page number in the textbooks. The method is simple and easy to follow.

- Learning at schools

The MoE’s second proposed contingency plan was to deliver limited education at school premises in smaller groups under specified health guidelines prescribed by the Ministry of Public Health. The delivery of this plan is currently almost impossible, especially in Kabul and other major cities, for two obvious reasons:

- Firstly, the Government of Afghanistan imposed a strict lockdown in densely populated cities across the country to slow down the spread of the virus. As people cannot come out of their homes, it is clear that face-to-face education on school premises cannot happen.

- Secondly, the lack of testing centres makes it impossible to know who, how many, and where have contracted the virus. Therefore, it is very risky to allow face-to-face activities and risk the health of teachers, students and their families.

Self-instructional material

In addition to these two measures, there have also been debates about the development of self-instructional material for education in Afghanistan. The content of these materials has been mostly borrowed from a handbook of Creating Learning Materials for Open and Distance Learning: A Handbook for Authors and Instructional Designers, published by the Commonwealth of Learning in Vancouver, Canada, in 2005. Although these materials are designed for an emergency, when learners do not have access to schools and teachers, the application of this idea is at least impossible for the current school year in Afghanistan because of several reasons:

- Firstly, self-instructional materials are meant to supplement the school textbooks and not to replace them.

- Secondly, they need to be printed and distributed to over 9 million learners across 18,000 schools in Afghanistan. The development, printing, and distribution of these materials under the current restrictions and for immediate use is an impossible task.

- Thirdly, children of the first cycle of primary level (grades 1-3) cannot use these materials independently. They need the help of their parents. However, as a large number of adults are themselves illiterate, many of the primary level children do not receive the needed support.

Distance education and the threats of educational divide

The COVID-19 outbreak has suddenly catapulted Afghanistan into the world of distance and digital learning. In the current situation, the technological infrastructure, especially the internet, is not at the level that can support distance and digital education at the national level. This problem is not unique to Afghanistan. Many other countries in the world are also struggling with similar issues. In the state of California, for example, 16% of school-aged children do not have access to the internet at home, while 27% of students access the internet through smartphones or tablets, which usually means slower speeds and not necessarily suitable for online education. Students’ access to the internet in Afghanistan is a much higher problem than that of California.

Poverty and a weak economy prevent students from accessing the limited technology available in Afghanistan. As shown in Figure 4, personal access to the internet is further affected by gender, geography, age, and education. Many families don’t even have electricity or a television set (see Figure 5), let alone a computer, internet and smartphones suitable for education. Also, the vast majority of families do not have a basic knowledge of the education system. For them, computers, the internet, and distance learning are unheard of. All their hope and reliance are on the school, the teacher, and the textbook, in the absence of which they do not even know how to help their children.

Moving from school education to distance learning (digital and non-digital) is a new, sudden, and difficult experience. Similarly, many students may even find moving back from distance learning to face-to-face education in the school environment a shocking experience. Digital literacy and access to digital technology are among the things that transform the existing economic and social divides into digital divides. The extended period of school closures transfers this digital divide to the school level and makes it an educational divide. Families with better digital literacy can help their children, and conversely, children of poor and digitally illiterate families are at risk of falling behind. As a result, the gap and divide between the children of rich and digitally literate and the children of poor and digitally illiterate families are widening very fast. The depth and breadth of this divide will be seen and felt when students return to schools and sit exam papers.

Despite all these challenges, the efforts of the MoE in Afghanistan are appreciated – especially in developing hundreds of hours of audio and video-based content for all 12 grades of general education and making those available via the internet and radio and television channels. While not much could be done to close the educational gap between the rich and the poor at this stage, there is still enough time to save the current school year and turn the crisis into an opportunity.

Thanks Yahia…well written and researched piece! Ed folks also need to research the impact of scheduled and unscheduled blackouts on viewership of videos lectures on TV. As video lectures are often connected to subsequent video lectures, my hunch is that Afg loses many distant learners (who.may not return) every day with every blackout as they fail to undeestand subsequent video.lectures As you said, MoE did a good job given the constraints. These video lectures developed by MoE shall act as a ready resource for the future at least for novice teachers who do not have tech or ped command over the subject. This is also a stating point to develop even better multimedia content which could be teacher or student facing for online/offline viewing.

With all the challenges associated wth self instructional material which you mentioned, we at the Ministry level had to include a no tech response as well like other countries (Colombia and Argentina for instance).There was no other way out for us.

Thanks for your comment, Vijay,

I hope you are keeping well and safe in this difficult time.

I agree with you that electricity blackouts not only affect learners’ attention and concentration but also deprive them of following distance learning lectures. I have referred to this issue in my Persian article, published in May this year on BBC Persian . This and other aspects of the current state of education in Afghanistan require urgent attention and in-depth research.

On self-instructional materials, I appreciate the Ministry’s efforts. I am glad that the idea was raised. These materials are going to be useful in Afghanistan, and I look forward to reading them as soon as they are ready.

Well written dear Yahia, is Samad Danish from Afghanistan presently pursuing Master in Public Administration in India , I am going to write a research paper, regarding the challenges and thereat of e-learning in Afghanistan.

Would help to find out relevant data for the same.

Regards.

Dear Samad,

Thank you for your interest in my article and your question.

The field of e-learning in Afghanistan requires original research. It is a new and unexplored area of education and research. E-learning materials in Afghanistan are primarily in the field of higher education. A limited amount of data have been processed and been made publically accessible. You will find some links to these materials on the official website of the Ministry of Higher Education. You also need to contact the Ministry and institutions of higher education to help you with data.

With best wishes.