This blog was written by Dr Edward Sosu, Reader and Director of Research, and Sofia Milheiro Pimenta, Research Assistant, School of Education, University of Strathclyde. It provides a brief summary of a recently published report entitled “Socioeconomic inequalities in learning opportunities, educational achievement, and mental health: impact of COVID-19 school lockdown in Ghana

In March of 2020, schools in Ghana were closed to mitigate the spread of the COVID-19 virus. While school closures are likely to have had a disproportionate negative impact on all children, the extent to which these effects vary by students’ socioeconomic and demographic characteristics remains unclear. Our study examined the nature of socioeconomic disparities in senior high school students’ learning experiences, mental health and trends in educational achievement during the COVID-19-related school closures in Ghana. Taking an intersectional approach, we investigated whether the impact of the lockdown varied across student socioeconomic status (SES), gender or location (rural or urban) in order to generate socioeconomic gradients of groups most negatively affected.

This blog highlights some of the key findings from our research based on a survey of second year senior high school students (n=1,481) enrolled in five different schools in Ghana shortly after schools reopened. The students completed a questionnaire detailing their SES (consisting of subjective family wealth, highest education of parent or guardian and experiences of hunger), experiences of learning and mental health during the lockdown. They also reported their educational achievement in English Language and Mathematics before the lockdown and took a short assessment in these two subjects during data collection.

Overall, our findings reveal significant socioeconomic status (SES) inequalities in students’ learning opportunities, mental health and trajectory of educational achievement during the period of school closure.

Learning opportunities:

Findings indicate that low SES students spent less time studying, and had less access to digital resources, books and extra classes. They also reported lower usage of these resources – except for the use of radio for remote learning. Participation in e-learning programmes was also lower among this group and they reported higher levels of engagement in domestic activities during the school closures.

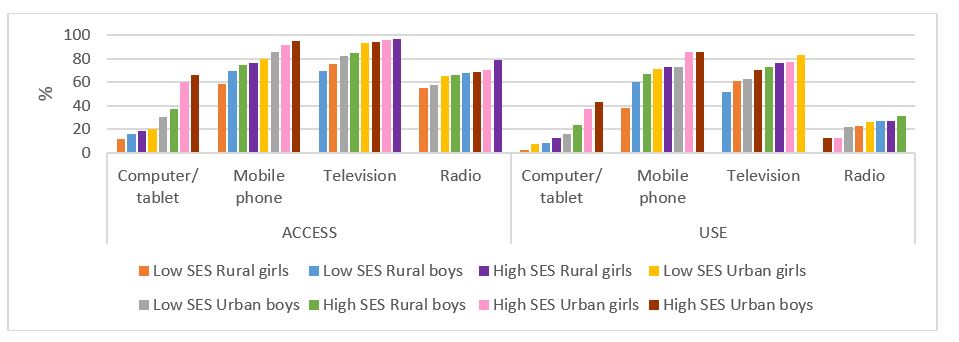

Intersectional analysis revealed the combined influenced of SES, gender and location on students learning experiences during the lockdown. For instance, in the exception of radio, low SES girls and boys and in rural areas reported the least access and use of the most common resources needed for remote learning during the lockdown (Figure 1). Overall low SES students reported the highest number of difficulties while high SES student reported the lowest number of difficulties during the school closures.

Trajectory of educational achievement:

Analysis of students’ trajectory of educational achievement suggest increases in the SES-achievement gap, albeit with significant nuances. Overall, while achievement for high SES students remained increased slightly, that for low SES remained flat.

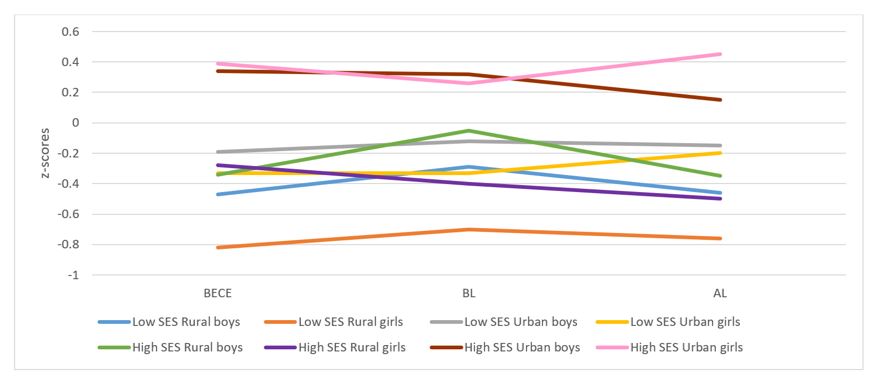

However, intersectional analysis (i.e. SES, gender, and location) indicated significant socioeconomic gradients and nuances of the impact of school closures on achievement. Low SES rural girls had the lowest achievement trajectory, while high SES urban girls demonstrated increasing trajectory of achievement during the period of school closures. There was also evidence of a ‘rural penalty’ in the trajectory of achievement resulting from the school closures, with high SES rural girls and boys showing significant declines in achievement over time, compared with low SES urban peers who demonstrated an increasing trajectory (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Socioeconomic gradient of achievement trajectories before and after the COVID-19 school closures.

Note: Achievement based on combined grades in maths and English. BECE – grades at Basic Education Certificate Examination; BL – grades obtained in last school test before lockdown; AL – grades obtained in object test after lockdown as part of data collection.

Mental health:

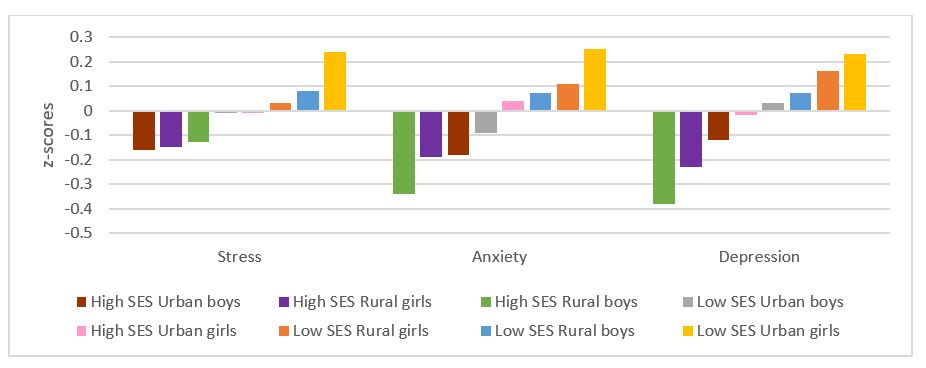

Results on mental health indicates that low SES students experienced the higher levels of mental health distress (i.e. household stress, anxiety, and depression). Intersectional analysis revealed that, overall, low SES urban girls reported the highest levels of household stress, anxiety, and depression.

Recommendations:

To tackle these SES-related challenges, we recommend that urgent policies and interventions are put in place by the government to address inequalities in all three areas. Such policies should adopt a systemic approach by creating partnerships between government, local authorities, schools, health and education boards in order to address some of the difficulties highlighted by this study. Particularly, in our report, we discuss the need to:

- develop a COVID-19 educational recovery strategy to support immediate and longer-term recovery, and address these three areas of inequalities;

- provide targeted funding for counselling services for students to mitigate the emotional impact of the pandemic,

- ensure that policies and interventions benefit the most disadvantaged students, that is, low SES students and especially those in rural areas, and;

- develop rigorous monitoring and evaluation of interventions that addresses these inequalities assuring that the long-term consequences of COVID-19 and the rural penalty are mitigated.