By Mieke Lopes Cardozo, Amsterdam Institute for Social Science Research, University of Amsterdam; and Cyril Brandt, Institute of Development Policy, University of Antwerp. These issues were discussed during a session at the September 2019 UKFIET conference on inclusive education systems.

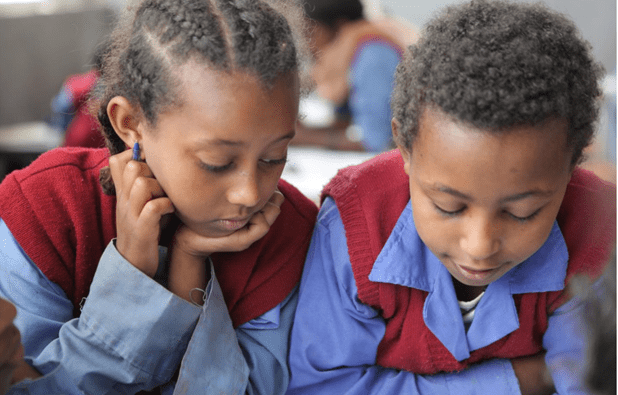

Teachers in protracted (violent) crises are to varying degrees expected to fulfil a multiplicity of functions such as facilitating learning outcomes, providing conflict-sensitive education, attending to traumatised students and representing the state. At the same time, they are often underpaid, receive little training and might themselves experience various forms of violence. An increasingly popular analytical frame is teacher well-being, which undoubtedly highlights important outcomes. We use this paper to identify potential conceptual caveats of a well-being perspective for analyses of teachers in protracted crises.

Teacher well-being

Well-being tends to prioritise individual and local-level perspectives over multi-scalar analyses. Common aspects of well-being include self-efficacy, resilience, stress and burnout. Some evidence exists on drivers of teacher well-being – high workload, insufficient salaries, violence, etc. However, few studies analyse underlying political economies of teaching professions, and teachers’ conflicted positionality, in protracted (violent) crises. Our goal is to enrich the well-being debate through a focus on these aspects.

Methods

We analyse evaluations of IRC’s Healing Classroom intervention in the Democratic Republic of Congo, wherein teacher well-being is central. We compare the evaluations with our Cultural Political Economy inspired qualitative research (since 2013) on teachers’ working conditions in various Congolese provinces. Poor funding, misgovernment and violent conflicts make the Congolese education system a relevant case to study protracted (violent) crises.

Context

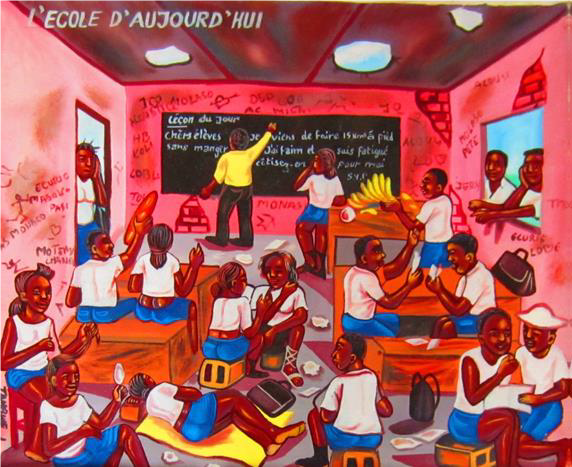

The Congolese education system has long been poorly funded. Since 1992, parents contribute to teachers’ meagre government salaries. In fact, they fund the lion’s share of all expenditures in primary and secondary education. Nonetheless, the Congolese education system has expanded since 2003, deploying teachers up until very remote villages. Large parts of the country have been affected by various violent conflicts since 1996. Destroyed schools, violence against teachers and a complex redeployment of internally displaced teachers are some of the negative impact of violent conflict on the education system.

Findings and main argument

Our emerging findings suggest that studying teacher well-being through local-level dynamics can yield interesting insights on certain drivers and effects. However, such a focus runs the risks of constructing localised socio-economic spaces that neglect national and global power relations, cultural political economies, the longue durée of conflict and teachers’ ambiguous role as state agents. Exploring these aspects could potentially be fruitful for a more thorough understanding of teacher well-being and teachers’ possibilities to act as change agents in protracted (violent) conflicts.