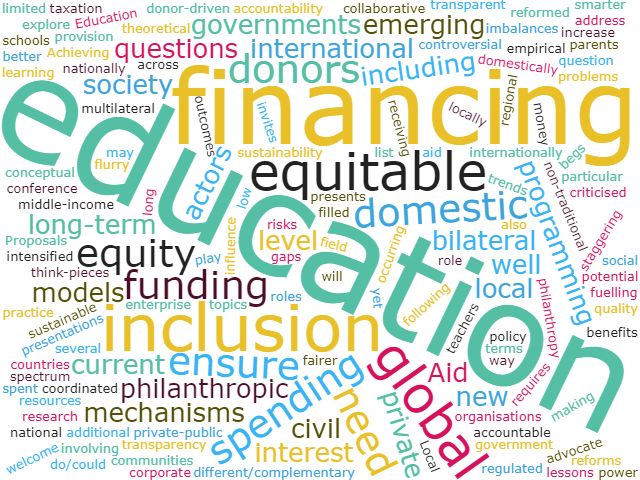

By Don Taylor, Deputy Chair of the UKFIET Executive Committee. These issues were discussed during a session at the September 2019 UKFIET conference on inclusive education systems.

This brief paper challenges the prevailing rhetoric on inclusion and inclusive systems. Whilst the aims of ‘leaving no-one behind’ and ‘ensuring inclusive and equitable quality education for all’, as enshrined in SDG4, are laudable, it is important to be realistic about what can and what cannot be achieved. It is a fallacy to assume or pretend that a national education system can meet the needs of literally everyone, given the obstacles and barriers involved. It would be so costly in most countries as to divert resources away from higher priorities offering better results and greater benefits. This is true whether we use a narrow definition of inclusion, focusing primarily on disability, or a broader definition recognising all the ways in which the vulnerable and the marginalised may be excluded from education.

This brief paper challenges the prevailing rhetoric on inclusion and inclusive systems. Whilst the aims of ‘leaving no-one behind’ and ‘ensuring inclusive and equitable quality education for all’, as enshrined in SDG4, are laudable, it is important to be realistic about what can and what cannot be achieved. It is a fallacy to assume or pretend that a national education system can meet the needs of literally everyone, given the obstacles and barriers involved. It would be so costly in most countries as to divert resources away from higher priorities offering better results and greater benefits. This is true whether we use a narrow definition of inclusion, focusing primarily on disability, or a broader definition recognising all the ways in which the vulnerable and the marginalised may be excluded from education.

In the first instance, there will be, in every community and nation, a number of individuals with multiple problems and such complex needs that the cost of enabling their access to the education system and of meeting their learning needs will be prohibitive, particularly in the poorest countries. There is no easy solution to this dilemma, but it cannot be equitable to spend unlimited amounts of scarce funds on these individuals. Particularly so, if the objective is to achieve the greatest good for the greatest number in pursuit of ‘Education For All’, of total inclusion.

Secondly, it is best for children to learn to read and write in their mother tongue, their first language, their spoken language, before they are expected to learn in another language. Given the diversity of languages used in most countries, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa, it would be prohibitively expensive to provide proper learning opportunities for every language group. The cost of training teachers fluent in each language, of deploying them appropriately, and of producing teaching and learning materials in all languages makes it completely impracticable. One consequence of this is that children of minority language groups are disadvantaged, which inevitably militates against genuinely inclusive education.

Thirdly, there are those children who are stunted in the earliest years of their lives as a result of poor nutrition. Their growth is impaired and their brains are so damaged that they will not be able to learn as fully or as quickly as other children in school. Rather than using scarce resources on inclusive remedial education, it might be better to invest in nutrition during the first 1,000 days of life (from conception to the age of 2 years). In the long run, this is likely to result in better social outcomes.

In each of these three situations, it is probable that the greatest benefits will not be attained through inclusive education. Better results could be achieved by allocating and using the same resources in a different way, by some alternative investment. Hence the need for ‘Value for Money’ studies and cost-effectiveness analysis, as a guide to national policy-making and resource allocation.

On a more positive note, the inclusion of girls, especially in secondary education, and the goal of gender parity in school enrolment, are the most important elements of inclusive education. The beneficial results and outcomes from female education are so great, and the numbers of people so large, that more should be invested in girls’ education than in boys’ education in many countries. It is argued that the allocation of resources should be disproportionately weighted in favour of girls.

The current pursuit of inclusion in secondary schools, of universal secondary education, as included in SDG4, also raises the issue of balance between the various levels in the education system and the corresponding allocation of resources between them. It is neither equitable nor ‘inclusive’ to spend ten times as much on the education of each secondary school student as is spent on the education of each primary school pupil. (According to the World Bank, Malawi spent 10 times as much on each secondary student in 2007 and 259 times as much on each university student as on each primary pupil). UNESCO estimates that there will still be 220 million children in the world in 2030 who are not enrolled in school at all. Surely getting them into school, and really learning there, would be a better investment than many of the other, lesser numerically significant, elements of inclusive education.

DFID’s Education Policy seeks to target support to ‘the most marginalised’, not just the hard-to-reach. The Concept Note for the 2020 GEM Report talks of the ‘funding formulas’ needed to meet the ‘additional costs’ of inclusion, as if those costs can be met however high they are. But there will always be limits on how much can be spent and what can be achieved. More realism is required, and less rhetoric.