This blog was written by Stephen Bayley, PhD Candidate at the Faculty of Education, University of Cambridge. These issues were discussed during a session at the September 2019 UKFIET conference on inclusive education systems.

The world is changing all around us.

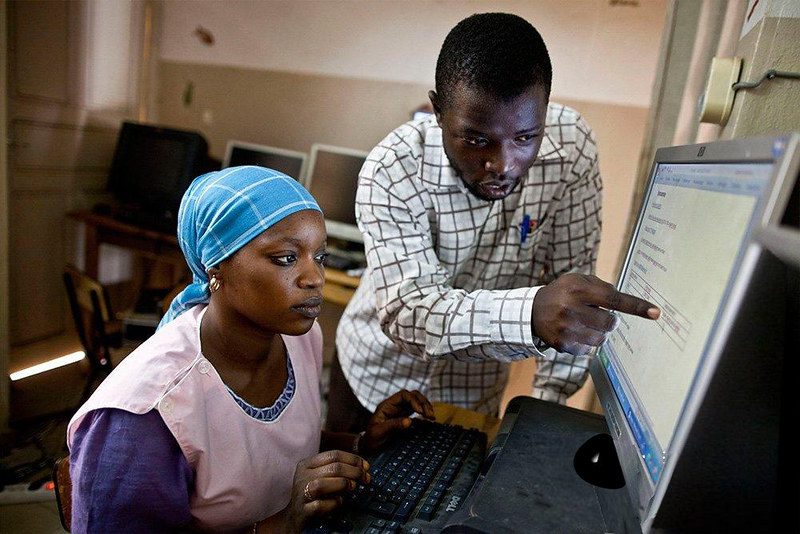

Across the globe, the explosion of technology has altered how we interact with one another, do business and live our lives. Many of the jobs of tomorrow may not even exist today and we find ourselves constantly having to predict or anticipate what the inventors and developers will come up with next.

Beyond technology, or perhaps because of it, scientists are warning us about irreversible climate change, and already we’re seeing increasingly extreme weather patterns – hurricanes and floods in some areas, droughts and famine in others.

And we’re contending with huge movements in global populations, an estimated 258 million migrants worldwide, of which nearly 70 million have been forcibly displaced by persecution, conflict and violence. These are people who have grown up and schooled in one context, now trying to build a life for themselves and their families in a very different setting.

We clearly live in uncertain and changing times, and arguably need to sharpen our skills for adapting to whatever may come next.

Demand for Adaptability Skills

Education systems have acknowledged these trends for some time and responded through the promotion of skills for adaptability such as creativity and problem solving. These competencies sit within many different learning frameworks which encourage teachers to foster so-called ‘21st century’ skills beyond basic literacy and numeracy. Indeed, a 2013 study of curricula in 88 countries ranked problem solving and creativity third and fourth behind only social and communication skills.

However, high-level policies and aspirations are one thing. Translating those ambitions into classroom practices and learning habits is another, and there are still many questions about how such skills can be nurtured, particularly in low-income and resource-constrained settings.

Diversifying Learning Outcomes

Many countries around the world, including in the Global South, have responded by introducing competence-based curricula to diversify their educational outcomes.

These curricula would appear to offer multiple benefits:

- They can help education systems and teachers to move away from theoretical and colonial content to more practical applications of local knowledge and skills relevant in the particular context or culture.

- They recognise, reflect and reward the diversity of children’s natural aptitudes, their multiplicities of intelligence, and their strengths and talents across different domains.

- Competence-based curricula make space and time for more holistic types of learning and thereby value more inclusive indicators of success.

To date, however, there has been limited evidence on the success of such approaches. Reviews from different countries report rushed and poorly-designed reforms, insufficient training for teachers on the new methods, ineffectively allocated resources and inadequate coordination with national assessment systems. Competence-based curricula may be useful for setting the direction of travel, but they don’t seem to necessarily offer the best roadmap.

Inclusive Skills Development

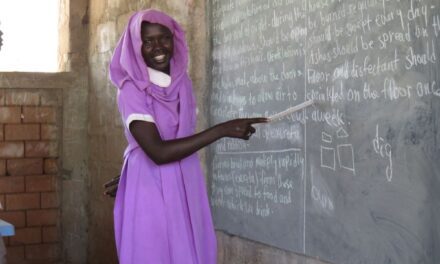

In light of these challenges, the 2019 UKFIET conference convened a panel of practitioners and researchers to discuss the future of skills provision in a session chaired by Dr Modupe Adefeso. Much of the conversation emphasised the particular importance of skills development for young girls and adolescent women, not least given the exclusionary effects of schooling that marginalises female learners and the disproportionate effect of climate change on girls.

Indeed, speakers from the Girls’ Education Challenge and CARE USA described the difficulties of defining and nurturing life skills for women in diverse global contexts. They outlined interventions to promote agency, leadership and resilience, and highlighted the need to confront gender norms to facilitate more enabling social and educational environments.

Laying Mental Foundations

Beyond targeting girls, the presenters also discussed the value of addressing the different mental building blocks that underpin 21st century skills and adaptability for the changing world. They raised the need to balance traditional outcomes with non-cognitive skills such as self-efficacy, -confidence and -esteem to empower and motivate learners in the development of their other competencies.

Greater support for learners’ cognitive flexibility could similarly offer benefits for life in the modern world. Leading neuroscientist Adele Diamond describes cognitive flexibility as “creatively ‘thinking outside the box’, seeing anything from different perspectives, and quickly and flexibly adapting to changed circumstances”.

Each of these components could foster a mix of 21st century competencies. For example, thinking creatively outside the box could aid innovation and experimentation to generate new jobs and livelihoods, and to try solutions that haven’t been attempted before. Seeing things from multiple perspectives could help people to understand differences between social groups, building tolerance and empathy as well as better communication and teamwork skills. Finally, adapting to changed circumstances might help us all with greater resilience in the face of political uncertainties, global migration and evolving technologies.

Skills for Tomorrow

Looking ahead, solutions for promoting 21st Century learning, cognitive competencies and non-cognitive skills remain under discussion and hotly contested. Within systems that already struggle to deliver basic outcomes like literacy and numeracy, it may seem overambitious or unrealistic to talk about such additional competencies.

However, the world keeps turning and time waits for no man, woman or child. Without concerted efforts to address these skills we risk leaving some of the most disadvantaged populations behind and unable to adapt to their changing environments. While literacy and numeracy may indeed provide important foundations, will they be sufficient not just to build communities and economies today, but also solve the problems of tomorrow?