This blog was written by Eva Bulgrin, a doctoral researcher at the Centre of International Education, University of Sussex and works as a freelance consultant in the areas of education, governance and migration in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Caucasus. Her doctoral research examines the discursive and social practices of actors involved in the delivery of pre- and primary education in the context of the decentralisation policy in Benin. For the 2019 UKFIET conference, 17 individuals, including Eva, were provided with bursaries to assist them to participate and present at the conference. The researchers were asked to write a short piece about their research or experience.

Introduction

Six weeks after the UKFIET conference, I want to reflect on my theoretical, professional and personal experience of having been part of this conference, actively engaging in the debates of the Future Directions of Inclusive Education Systems theme. More specifically, I intend to address three aspects, which are the synergies of being part of a symposium, the added value of using the concepts of space and place in theorising educational governance in a post-colonial setting, and the personal and lived experience of the UKFIET conference.

The synergies in presenting with colleagues at a symposium

I appreciate having had the opportunity to take part in a symposium about the “Struggles for inclusion: spatial analyses of education in Africa”. This symposium presented an excellent opportunity to think together through the same lens, despite different foci and experiences. In particular, it helped to focus and sharpen my thoughts on the “Post-colonial imaginaries of educational governance in Benin”, while feeling professionally and socially supported.

The added value of using the concepts of space and place in theorising educational governance

In line with Massey (1994: 2), who argues that space and time are integral to one another, I provided a historical exploration of educational governance in two local field sites in Benin in 2017, extending this to include an analysis of national and global influences on policy formulation and mediation from 1990 onwards. If the spatial is conceptualised in terms of space-time, a place can be considered as ‘a particular articulation of those relations, a particular moment in those networks of social relations and understandings'(Massey, 1994: 5).

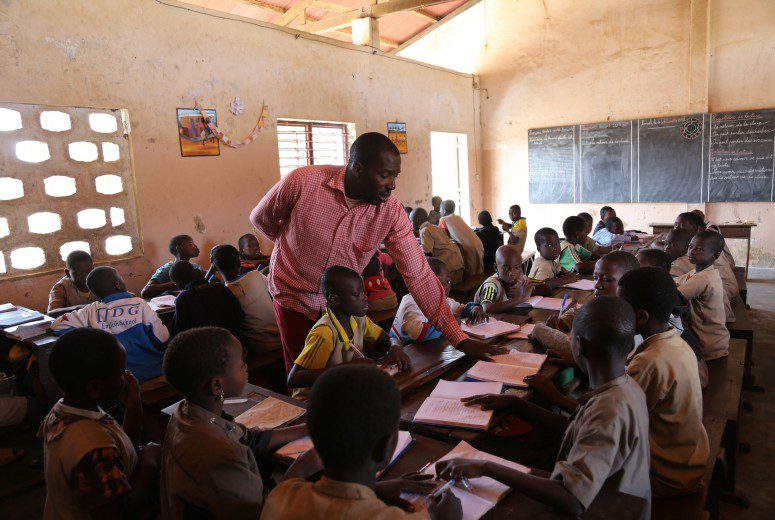

In this presentation, I first focused on the mediation of the decentralisation policy, considering it as a social arena allowing for institutional and relational pluralism (Ball, 1993). In adopting a spatial lens, exploring the discursive and social practices of teachers, parents and municipal officials in a Northern and a Southern field site, I disentangled the messiness of the policy practices on the one hand, and the nuances, on the other. For example, I showed how NGOs navigate the terrain in the North, and school actors collaborate with the central administration, rather than with municipalities, in the South. Overall, I discussed a tendency of strengthened central and municipal government entities and the potential exclusion of voices of parents, teachers and students in the policy text.

Second, I de-constructed the policy text to demonstrate how the colonial experience under French occupation and the dominant development discourses are interwoven in the conceptualisation of educational decentralisation. I argued that the National Policy of Devolution and De-concentration could be considered as a (neo-) colonial bricolage for at least three motives:

- Ideas of modernisation and development inform the policy text.

- The territorial administration legally inscribed in the policy has its roots in the colonial administration.

- International Organisations (IOs) and consulting firms have powerfully influenced the policy formulation.

Even though Benin gained independence in 1960, it continues to be framed by colonial discourses of development. The policy of decentralisation, promoting access to social services, socio-economic development and, implicitly, participation, is such an example (Bierschenk, 2009; Fichtner, 2012).

In summary, I demonstrated how the analysis of the local and a focus on the spatial power dynamics in context are more informative than the single temporal focus on the achievement of decentralisation as a policy imperative. Instead of considering the local as a deficit, it can be rather found in the universalised policy. In light of uneven power relations in the formulation and enactment of the policy of educational decentralisation and the insignificance of the specificities of local contexts, I argued that inclusion remains a challenge to deal with beyond development policies.

The lived experience of UKFIET

The conference took place in an intense but inspiring setting. The historical environment of New College, with its 14th century architecture, its medieval dining room and its church bells, pervaded the debates on education and inclusion in the Global South today. If we understand the spatial as space and place – the conference venue as the place and the social relations of simultaneity and multiplicity as space – it produced simultaneous and multiple debates on education and inclusion, which spoke to each other, inspired and challenged one another.

Conclusions

For me, using the lens of space and place has provided new ways of looking at how education governance is framed to unpack the Future Direction of Inclusive Education Systems.

References

Ball, S. J. (1993) ‘What is Policy? Texts, Trajectories and Toolboxes’, Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 13(2), pp. 10–17. doi: 10.1080/0159630930130203.

Bierschenk, T. (2009) ‘Democratization without development: Benin 1989-2009’, International Journal of Politics, Culture and Society, 22(3), pp. 337–357. doi: 10.1007/s10767-009-9065-9.

Fichtner, S. (2012) The NGOisation of education : case studies from Benin. Köln: Ruediger Köppe Verlag.

Massey, D. B. (1994) Space, place, gender. Cambridge: Polity Press.

I came across this site and found something relevant which I did not found from last 2 months and I gathered such a great knowledge for which I were looking for

Thanks