The UKFIET 2019 conference had 6 themes relating to Inclusive Education Systems. The co-convenors for the theme ‘Future directions in education systems for the 21st Century’ were Dr Ricardo Sabates from the Faculty of Education and member of the Research for Equitable Access and Learning (REAL) Centre, University of Cambridge, and Dr Shrochis Karki, Education Systems Lead at Oxford Policy Management. And the Rapporteurs were Seema Nath (PhD candidate) and Jude Hannam (MPhil student) both at the Faculty of Education, University of Cambridge.

Is there an Elephant in the System? (what do you think it is?)

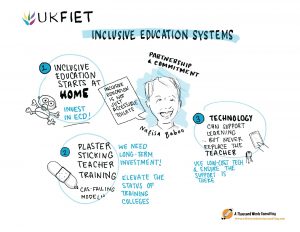

How do we ensure that equitable access and quality education for all are achieved within a generation? This was the challenge Nafisa Baboo, Senior Director, Inclusive Education for Light for the World, posed to us during the opening plenary of the 2019 UKFIET conference. In addressing such a challenge, presentations focused on systemic approaches, quality provision, teachers and teaching, education in challenging contexts, disability and inclusion, and the role of technology. At the core of the conference, presentations touched on innovations, diverse and distinct approaches, locally addressed solutions, and potential for scalability of solutions. Our theme had one additional challenge, to think out loud – and perhaps differently – about the future.

How do we ensure that equitable access and quality education for all are achieved within a generation? This was the challenge Nafisa Baboo, Senior Director, Inclusive Education for Light for the World, posed to us during the opening plenary of the 2019 UKFIET conference. In addressing such a challenge, presentations focused on systemic approaches, quality provision, teachers and teaching, education in challenging contexts, disability and inclusion, and the role of technology. At the core of the conference, presentations touched on innovations, diverse and distinct approaches, locally addressed solutions, and potential for scalability of solutions. Our theme had one additional challenge, to think out loud – and perhaps differently – about the future.

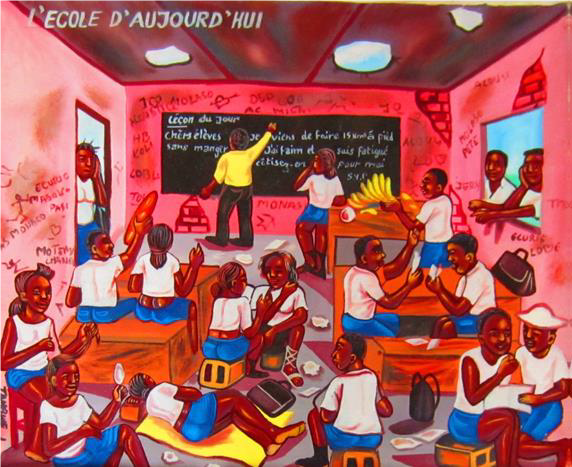

As expected, presentations under the sub-theme “Future Directions in Education Systems for the 21st Century” focused on whether existing educational systems have enabled access to quality learning for children. And additionally, whether access and learning are influenced by children’s locations, ethnicities or religious backgrounds; gender or sexual identities; and wealth or resources available to households, schools, and communities. Some presentations focused on attempting to discover a consensus on the kind of skills required for the 21st century and how best to promote these skills within current educational systems or, alternatively, outside them. Presentations also focused on different levels of education: early years for a more equitable start and post-secondary schooling for supporting future livelihoods.

Anna Robinson-Pant, closing the second day of the conference, contended that formal education was too narrow a focus and wondered whether we ought to consider widening the angle of our gaze in order to gain better insights into the challenges facing the global education community. She listed intercultural learning, informal learning, inclusive education, and task conscious learning as some areas that require further consideration. Her plenary address was deeply insightful, and she worked with the Mandala theatre group in Oxford to dramatise and bring to life some of the challenges and issues children and young people face in low income contexts (videos of these dramatisations are available here).

|

|

|

The presentations in our theme provided deep and varied insights, and it is a challenging ask to summarise them in a short blog. Nonetheless, we present below some of our key takeaways from our sessions.

Future directions in early learning provision:

While institutional forms of early childhood care and education (ECCE) have been reaching large numbers of children, it is unclear whether much of the current provision is fit for purpose. In some cases, presenters suggested that low quality provision could actually increase educational inequalities rather than reducing these. Additionally, ECCE tends to be too narrowly tied to school readiness, and ECCE sites are often seen as places to provide health and nutrition (for example, the provision of meals, health checks and immunisations). Many ECCE centres in low-income contexts lack the broad developmental provision that is required for enhancing the socio-emotional and academic skills of children. Attendance to ECCE in many low-income contexts is irregular, with movements in, out and between ECCE Centres, which are often unregulated. A missing piece of the ECCE conversations about the future concerns alternative forms of practices, including home and community-based, as well as innovative assessments to capture a broad range of skill development.

Community initiatives with strong support from parents could be viewed as a potential future direction. Parents have strong critiques of dominant school-based systems and hence parents should be given more space in the design, planning, and provision of early childhood for their children. However, scalability and particularly the role of the government in the regulation, accountability, and monitoring of these local initiatives is proving to be challenging, and perhaps not within the main priorities for state provision. This is particularly the case in regions with large refugee communities, ethnic minorities and remote rural areas, where ECCE provision could provide a more solid start for young children.

Future directions in skills:

While foundational literacy and numeracy are key skills for the 21st century, a deeper understanding of non-cognitive skills is necessary in order to promote a more holistic cognitive and socio-emotional developmental experience for children in schools and communities. Whilst there was no single definition of these vital skills, most presentations included:

promote a more holistic cognitive and socio-emotional developmental experience for children in schools and communities. Whilst there was no single definition of these vital skills, most presentations included:

- social skills, which are key for building tolerance and cohesion;

- communication skills, which are central to social relations, business, and politics;

- adaptability skills, which are important for experimentation, future innovations, and seeing things differently.

Other important skills also include development of confidence, self-esteem, perceptions of self and others as well as tolerance to diverse socio-cultural norms. Additionally, research presented at the UKFIET conference focused on the gendered nature of some skills, as well as gender differences in the formation of such skills and the limiting factors in a girl’s environment which could hinder her development.

There are immense challenges in measuring holistically the development of cognitive and non-cognitive skills during childhood and adolescence. The development of these skills changes in complex ways as children grow up, and their enhancement depends on many other intersecting, contextual, and cultural conditions. In terms of future directions, we require deeper and more contextually relevant understanding of

- how non-cognitive skills for both boys and girls are interpreted in light of social norms, values, and local knowledge;

- how these can be successfully taught within and outside the formal education system;

- and whether these influence broader economic and social outcomes.

Future directions for the learning of children with disabilities:

Recent years have seen increasing global commitments to improving disability data in order to deeply understand the educational status of children  with disabilities. One source, the Washington Group on Disability Statistics, has been used in several countries over time and has shown that while access to school for children with disabilities is on the rise, their learning continues to lag behind those children without disabilities, and girls with disabilities are particularly negatively affected.

with disabilities. One source, the Washington Group on Disability Statistics, has been used in several countries over time and has shown that while access to school for children with disabilities is on the rise, their learning continues to lag behind those children without disabilities, and girls with disabilities are particularly negatively affected.

Presenters drew attention to the fact that despite the availability of better data, large numbers of children with disabilities are still invisible. There is a need to collect disabilities disaggregated data, and the need to make EMIS forms more carefully worded and inclusive to capture information on disabilities in a respectful manner in the future. Research needs to explore how supporting learning of children with disabilities relates to the learning of all children. Training teachers to be more inclusive to children with disabilities could help teachers be more inclusive of everyone.

Finally, enhancing inclusion for children with disabilities requires greater social inclusion across society. Therefore, the future of research in this field is firstly for policy-makers and other actors to utilise the growing data to ensure that disability inclusion is realised and secondly to continue to provide evidence that living with disabilities means challenging the social norms of the ‘everyday’ life. This often requires dealing with unseen biases in terms of intersectionality of disability with gender, class, caste, and religion, which still prevent many from reaching their potential.

Future directions in secondary school and beyond:

Effective secondary schooling is paramount to enabling adolescents to acquire the skills and confidence needed to transition to work and succeed in life. These factors also facilitate social and economic transformation. However, there are many young people in low-income countries who fail to enter secondary education, whilst those who are enrolled achieve learning outcomes well below international levels. Future research on secondary education should investigate the financing of secondary education, the provision of skills for achieving livelihoods, including skills that will facilitate innovation and experimentation. Future employability has to be reconceptualised as the labour market is unlikely to absorb the growing number of school graduates. We need to strongly embed education for sustainable development into the curricula to ensure increased awareness and attitudinal change from the future generations.

Future Directions for Scalable Solutions:

There is a plethora of evidence of small scale, well-resourced projects which have shown significant improvements in learning outcomes for children. But most of this evidence fails to show effectiveness at scale. At the same time, there are policies and legislations aiming to promote inclusive education by supporting teacher motivation, retention and continuous training, and provision of materials and other inputs. However, these policies, while visible, lose focus and effectiveness during implementation and enactment in schools.

In terms of future directions, small scale interventions need to demonstrate not just whether children are learning, but why they are. Information on costs linked to the intervention should be used for exploring the potentials for cost effective scalable solutions. We must promote equitable educational development for children in locations and for populations where implementation of scalable solutions is still a challenge, such as in remote areas, for refugee children or those with disabilities. Finally, we need to understand that systems operate within socio-cultural contexts and any scalable solution must address this critical issue.

Future of Indigenous Knowledge within Inclusive Systems:

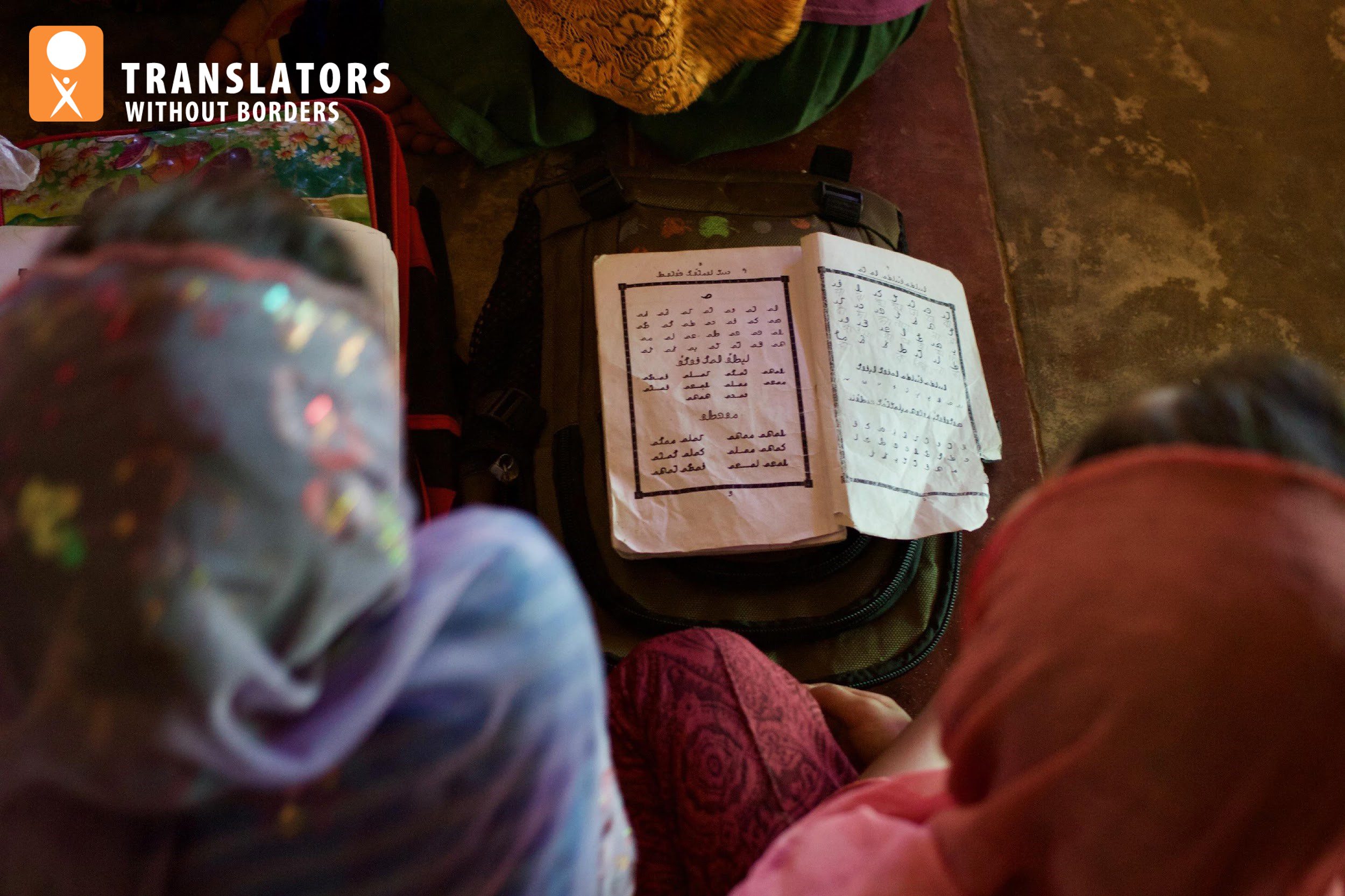

Using local indigenous knowledge in interventions has proven to be a powerful way for raising learning outcomes for local populations. Unfortunately, lessons from these small-scale interventions have not been taken into consideration for adaptability to other contexts and potential for scalable solutions. National and regional solutions continue to ignore indigenous understandings, which is likely to lead to increased marginalisation of these groups.

Several presentations at the UKFIET conference highlighted potential solutions to include local knowledge in inputs of education (such as textbooks or technology), but also improving the processes by which education can effectively be provided utilising indigenous pedagogical approaches. In terms of future directions, research needs to focus on the understanding of indigenous skills, their effectiveness and the inclusion and amplification of indigenous voices and knowledge in education to continue to strive towards a more inclusive system.

Future of Research for Inclusive Systems:

The UKFIET conference provided a space for sharing experiences between researchers, practitioners and policy-makers, many of whom come from  diverse disciplinary backgrounds and professional experiences, and who utilise different methodologies for exploring inclusive educational systems. How these different disciplinary and methodological traditions communicate with each other continues to remain a challenge for the future of research in this area. Local and international organisations and researchers are working to increase new sources of information and local understandings of the contexts. Yet there is limited availability of multidisciplinary approaches for undertaking systems research.

diverse disciplinary backgrounds and professional experiences, and who utilise different methodologies for exploring inclusive educational systems. How these different disciplinary and methodological traditions communicate with each other continues to remain a challenge for the future of research in this area. Local and international organisations and researchers are working to increase new sources of information and local understandings of the contexts. Yet there is limited availability of multidisciplinary approaches for undertaking systems research.

The UKFIET conference provided a platform for policy-makers, practitioners and researchers to attend workshops, training and exchange ideas. The future direction of research for inclusive systems needs to incorporate voices from all stakeholders, be undertaken in a truly multidisciplinary fashion, and with a focus on understanding and unpacking the complex ways in which educational systems operate to achieve an inclusive environment.

Closing remarks

Looking at some of the emerging issues on the future of inclusive education systems we raised the question: is there an elephant in the system? Is there an obvious solution for enabling more inclusive systems of education for the future? It seems that there should be quality and equitable education and care to all children so that their individual social and intellectual potential is reached. The challenge is how. Fortunately, presentations during the 2019 UKFIET conference provided interesting insights and future directions for enabling more inclusive education systems.