This blog was written by Catherine M. Jere, School of International Development, University of East Anglia, in response to the launch of the GEM Gender Report on 5th July 2019.

The latest in the series of Global Education Monitoring (GEM) Gender Reports was launched at the G7 France – UNESCO International Conference on Friday, 5th July 2019. The new Report, “Building bridges for gender equality”, applies a gender lens to the latest education statistics and key findings from the main 2019 GEM Report on migration and displacement. The Report indicates that while progress has been made in tackling the challenges of gender disparities, more needs to be done to secure gender equality in education.

Gender gaps widen across education levels

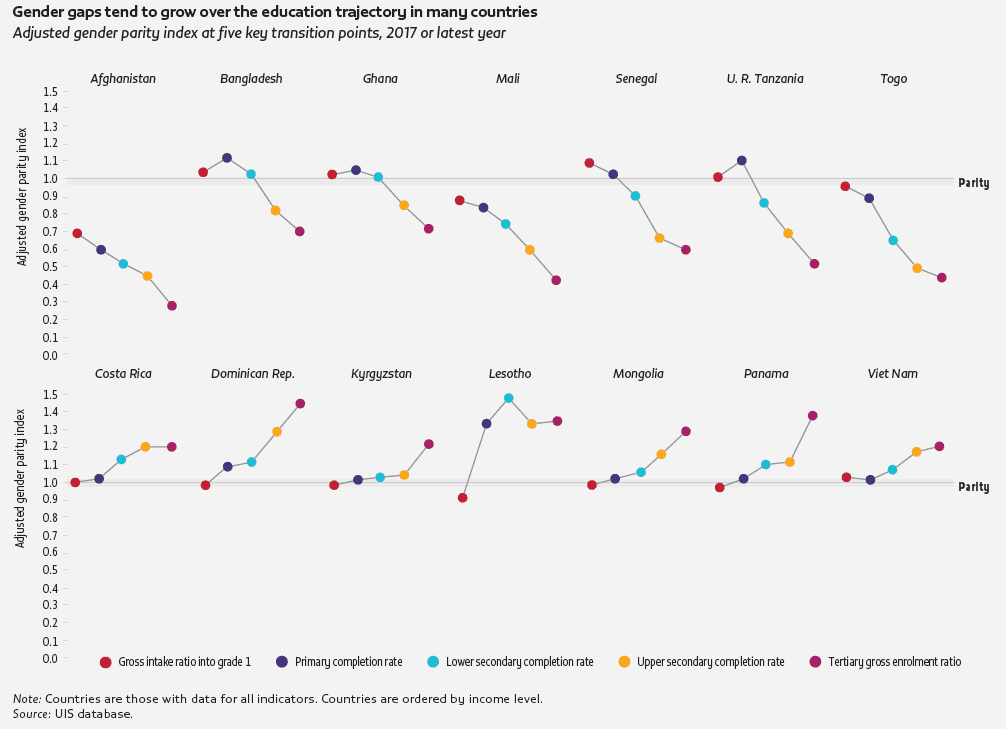

The Report’s analysis shows that while gender parity –equal numbers of girls and boys– in primary and secondary enrolment has been achieved globally, this progress masks substantial gender gaps within many countries. Just two in three countries have achieved gender parity in primary enrolment, one in two in lower secondary, and one in four in upper secondary education. Overall, girls are more disadvantaged in low-income countries, while a quarter of countries – mainly upper-middle-income countries – have fewer boys in upper secondary education, with no change since 2000.

Many countries are further still from achieving gender parity in tertiary education, with gender gaps widening as education levels rise (Figure 1). In Ghana, for example, equal numbers of boys and girls enrol in primary education, while far fewer girls complete upper secondary or enrol in tertiary education. Conversely, in Mongolia, while equal numbers of boys and girls enrol and complete primary education, boys are less likely to advance in their education. Many of the ‘push and pull’ factors that influence these gendered patterns of enrolment are explored in this Report.

Figure 1: Gender gaps widen across increasing education levels

2019 GEM Report analysis: gender parity index of between 0.97 and 1.03 indicates parity; above 1.03 indicates disadvantage to boys, below 0.97 indicates disadvantage to girls.

For learners reaching post-secondary levels, technical and vocational programmes remain dominated by male students, while the opposite is true for tertiary education. Subject choice is also gender segregated: just over a quarter of students enrolled in engineering, manufacturing and construction courses and in IT programmes are female.

Drawing on analysis from the 2019 GEM Report, this review demonstrates how gender, poverty and location intersect to reduce educational opportunities, with girls and boys from the poorest households still facing significant barriers to attaining a full education. Displacement and migration exacerbate these inequalities.

Entrenched social norms impede gender equality in education

A key theme of the Report is that a more concerted effort is needed to address discriminatory social norms and values, if gender equality in education is to be achieved. Its analysis examines how such norms underpin inequalities within families, schools, social institutions and educational policy.

Gender norms that place little or no value on girls’ and women’s education, and reinforce care-giving roles, restrict their chance of equal participation in education. The Report highlights the plight of child domestic workers who, in most countries, are more than twice as likely to be girls. Research from Ethiopia, Indonesia and Peru shows that poor rural girls frequently migrate to cities out of poverty, often unaccompanied, end up in domestic work and see their education opportunities compromised. The Report also calls for more political commitment to ban child marriages and protect girls’ right to return to school after pregnancy. In sub-Saharan Africa, four countries – Equatorial Guinea, Sierra Leone, U.R. Tanzania and Togo – enforce a total ban on pregnant girls and young mothers in public schools.

The teaching profession itself is highly gendered. Very few men work in early childhood education, for example, at least partly because of persistent gender stereotypes and norms. Even where the majority of the teaching workforce are female, few make it into leadership positions. In Japan, where, overall, 39% of teachers are female, only 6% are head teachers. Many low-income countries struggle to deploy female teachers where they are most needed, as in displacement and post-conflict settings. There is inadequate training in gender-sensitive teaching, which reinforces gender stereotypes in the classroom: impacting on both girls’ and boys’ life choices.

Making gender equality in education a priority

The 2019 Gender Report examines the reasons why many countries around the world are yet to achieve gender parity in primary, secondary and post-secondary enrolment and completion, and still have far to go to ensure broader gender equality in and through education. SDG targets 4A and 4.7 not only call for education facilities to be gender sensitive, safe and non-violent, but require learners to gain knowledge and skills to promote a sustainable vision of development that includes gender equality. As such, support for education systems needs to move beyond counting numbers of learners in schools to include curricula and textbook reform, comprehensive sexuality education, teacher education and institutional change as priority areas.

Results from the GEM Report team’s survey of key actors in international development show that while girls’ education is a priority area for many donors and governments, more could be done to embed gender equality within budgets and education plans. On average, across OECD donor countries, 55% of direct aid to education in 2017 was deemed gender-targeted (including gender equality and/or women’s empowerment as a programme objective), ranging from just 6% in Japan to 92% in Canada. Spending largely reflects donor country priorities. The UK, for example, has invested in two rounds of the ambitious Girls’ Education Challenge initiative, which currently operates 27 projects in 15 countries. Two evaluations praised its focus on gender equality, but indicate a need to address sustainability and strengthen links to learning outcomes.

Working with a broad framework for gender equality in education

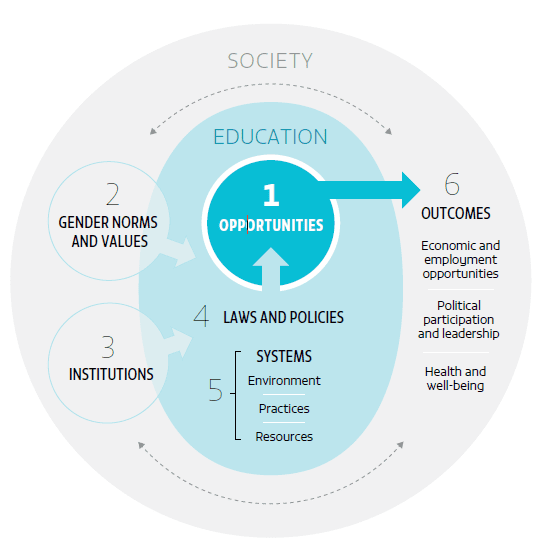

Since developing a monitoring framework for gender equality first introduced in the 2016 GEM Report, the GEM Report team are partnering with UNGEI, UCL Institution of Education, and other institutions in the UK, Malawi and South Africa to develop an indicator framework that supports work on gender equality indicators for the SDGs, particularly targets 4.7 and 4A. The project ‘Accountability for Gender Equality in Education’ is funded by the UK Department for International Development (DFID) and the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC). The monitoring framework considers gender equality in education across 6 domains: opportunities for access and learning, gender norms and values, social institutions, laws and policies, education systems and outcomes (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Framework for monitoring gender equality in education

While data remain sparse in several areas, the 2019 Gender Report presents an important attempt to demarcate what real and transformative progress across these domains for gender equality in education might look like.

Women Equality demands the empowerment of women, with a focus on identifying and redressing power imbalances and giving women more autonomy to manage their own lives. women make up more than two-thirds of the world’s 750 million adults without basic literacy skills; women represent less than 30% of the world’s researcher.

https://eeleanor.com/

thanks for info.