This blog was written by Catherine M. Jere, School of International Development, University of East Anglia. Catherine is a member of the UKFIET Executive Committee.

On March 8th 2018, to mark International Women’s Day, UKFIET, together with the Gender and Development Network (GADN), hosted the launch of the sixth Gender Review from UNESCO’s Global Education Monitoring (GEM) Report team. The event brought together academics, practitioners and activists to reflect on and discuss the progress made towards achieving gender equality in education, challenges that continue to exist, and how to strengthen commitments through better accountability.

This packed event took place at the Royal Over-Seas League in London, dexterously moderated by the well-known journalist and BBC Radio 4 presenter Ritula Shah. William Smith, Senior Policy Analyst at UNESCO and of the GEM Report’s lead authors, opened the launch with a thought-provoking summary of key findings from the 2018 Gender Review ‘Meeting our Commitments to Gender Equality in Education’.

The presentation was followed by a panel discussion with leading experts and a lively question and answer session. The expert panel, joined by William Smith, consisted of:

Amy Parker, Global Technical Lead, Relief International and co-chair of the GADN Girls’ Education Working Group

Lucia Fry, Research and Policy Manager, Malala Fund

Esme Kadzamira, Research Fellow, Centre for Education Training and Research, University of Malawi

Delphine Dorsi, Executive Coordinator, Right to Education Initiative

The GEM Report presentation highlighted shortfalls in securing gender equality in education and proposed solutions to the challenges faced, with a focus on improved accountability. That is, not just measuring the differences in education opportunities between males and females, but strengthening and monitoring change in legislation and policies, institutions and practices – both inside and outside of education systems – to build greater equity ‘in’ and ‘through’ education. Key to this is the setting of clear roles and responsibilities for governments, civil society, teachers, students – and their families.

Gender equality in education requires not only that girls and boys, women and men, have an equal chance to have access to and participate in education, but also that there are quality, equitable learning opportunities and outcomes. Panelists noted that even in countries where girls and boys achieve equally well and gain similar levels of education, women are still under-represented and face disproportionate disadvantage in political, economic and civic life.

The Gender Review outlines how disparities exist in subjects studied, among chosen professions and leadership, including within the teaching profession. William Smith shared the example of Japan, where almost 40% of teaching staff in secondary schools are female, yet only 6% are head teachers. In the Republic of Korea, this ratio is more extreme, with women making up 68% of teaching staff, but only 13% of head teachers. Even fewer women occupy leadership positions in higher education. And although, globally, women outnumber men as university graduates, they lag far behind men in completing science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) degrees and pursuing careers in STEM professions.

To monitor progress on gender equality in education, a new framework is required. Discussions noted the need to develop means to measure social norms, values and attitudes, education policy and planning, resource allocation, teaching and learning practices and means to ensure inclusive, safe and non-violent learning environments. Esme Kadzamira, sharing her experiences from Malawi, highlighted the urgent need to address school-related gender based violence (SRGBV) that can act as a major barrier to girls’ (and boys’) participation in a quality education, as well as perpetuate violence in wider society.

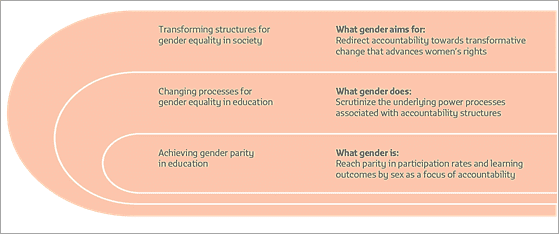

Figure 1: Different concepts of gender and gender equality have different implications for accountability Source: UNESCO GEM Report Gender Review 2018

The GEM Report team presents three ways of considering the meaning of gender and gender equality, and the implications of this for accountability in education (see Figure 1). A discussion of what the concept of gender aims for requires a critical review of accountability outcomes in education, considering whether they advance or undermine women’s and girls’ rights, capabilities and social justice. Lucia Fry, of the Malala Fund, reiterated the importance of tackling underlying structural barriers to gender equality.

While the Education 2030 Framework for Action recognises the essential role of gender equality in ensuring the right to education for all, many governments are yet to commit fully to gender equality in education. Analysis for the 2018 Gender Review indicates that only 44% of countries have ratified all three international treaties that refer to gender equality in education:

While the Education 2030 Framework for Action recognises the essential role of gender equality in ensuring the right to education for all, many governments are yet to commit fully to gender equality in education. Analysis for the 2018 Gender Review indicates that only 44% of countries have ratified all three international treaties that refer to gender equality in education:

1. the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW)

2. the Convention against Discrimination in Education (CADE)

3. the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR).

Although 189 states have ratified CEDAW, many have included reservations, such as reservations against the prohibition of forced marriage and child marriage. Panellists also noted the huge challenges of enacting policy to promote gender equality in education, especially where there are limited resources and poor district and community support for change.

Debates and discussion from the day brought together a number of recommendations. These included:

- the importance of developing gender-sensitive education sector plans and carrying out a gender assessment of policy implications, budgeting and resource allocation

- greater gender balance in school and other leadership positions

- reviewing and addressing gender bias in curricula, textbooks and teaching methods

- revoking discriminatory legislation, such as that which bans pregnant girls from school

- tackling gender-based violence in schools and communities and working with a range of actors to challenge and transform gender norms.