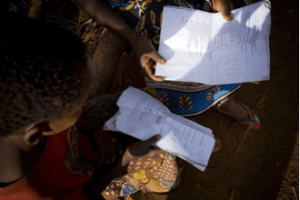

Girl discussing her school report with her mother in Northern Tanzania. Photo Credit: Kate Holt/Shoot the Earth/ActionAid

The burgeoning discourse on girls’ education in a post-Millennium Development Goal world emphasises rights and quality as fundamental factors to supersede a focus so far on access. Education programmes that concentrated on increasing girls’ enrolment in primary school have had significant success: the 2012 UN MDG Report announced global gender parity in primary school enrolment. However, efforts have also shown that increasing enrolment does not usually change gendered attitudes and behaviours in and around schools. Systemic gender discrimination continues to obstruct girls’ experiences of quality schooling and their lives beyond school. Poverty, pregnancy and early marriage remain three of the most intractable obstacles facing girls today.

Simultaneously, a results-orientation to education interventions is prevalent among many donors, including payment by results conditions. While measuring enrolment as a proxy for access (however insufficient) is relatively straightforward, measurements of quality and the promotion and protection of rights in schools and education systems is more difficult. Plan’s 2012 State of the World’s Girls report, launched on the first UN Day of the Girl this October, emphasises the education rights of adolescent girls and queries methodologies for measuring girls’ actual experiences in school and their status within their families and communities. How do we measure success in quality, rights-based girls’ education (with a deliberate emphasis on girls as specifically and systematically marginalised rights-holders)? What should we measure? How can we increase the credibility and reliability of results?

In my experience, measurements of success must go beyond an over-reliance on quantitative data to include qualitative data and data directly from beneficiaries, especially girls. We need to strengthen the inter-relationship of quantitative and qualitative data and avoid the pitfall of viewing qualitative data as inferior. We should, as others have suggested, integrate beneficiary data into national data collection cycles and support capacity development programmes for national education officials to run rigorous data collection and analysis cycles as a core component of their education system.

Plan’s Girl-Friendly School Scorecard and ActionAid’s Promoting Rights in Schools approach intend to value and centralise girls’ and other rights-holders’ perceptions and measures of their schools and education systems in order to advocate for quality and equality improvements. It is hoped that this type of data collection and analysis will improve understanding of actual gendered processes, attitudes and behaviours at work and how to address them, at community and national levels.

Indeed, we need to better understand and measure the stages of knowledge, attitude and behaviour change that contribute to transforming girls’ education. Self-completed questionnaires tend not to reveal whether knowledge of child marriage, for example, translates into sustained, genuine behavioural change – the inadequacy of mechanisms to measure behaviour change is, as experts have highlighted, a major obstacle to determining success in girls’ education.

Lastly, to understand what works to deliver long-term transformation for girls’ education we need to holistically re-validate our interventions several years after their completion. Only then can we get to grips with ‘success’ in quality rights-based education for all girls.

Disclaimer: The views expressed are the personal opinion of the author may not be shared by ActionAid International or other organisation.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks