This blog was written by Abigail Kajumba, Executive Director of Emerging Public Leaders and Wendy Kopp, CEO and Co-founder of Teach For All.

The world today faces unprecedented polycrises–environmental shocks, political instability, economic volatility–all converging in ways that demand resilient systems built upon human capacity and collective leadership. Yet historically, our global systems, particularly foreign aid, have dramatically underinvested in local leadership and agency. For instance, in 2018, only $15.2 million of Official Development Assistance (ODA) was invested in leadership development according to a study by the Boston Consulting Group, representing just 0.01% of the approximately $149.3 billion in total ODA for that year. This gap has left communities vulnerable, precisely when local agency is most needed to navigate uncertainty.

What if it had been different? What if, as well as addressing acute needs within low-income countries, foreign aid had over the past decades prioritised investing deeply and deliberately in cultivating the next generation of local leaders, such as educators, civic innovators, and public health professionals? Today, even with the global aid architecture shifting and traditional models rapidly being dismantled, there would be a stronger foundation in a robust, resilient, and interconnected network of locally-rooted leadership. This leadership would be more equipped to be innovating solutions, adapting in real time to crises, and drawing on deep contextual understanding of the communities they serve as well as their networks with similarly-situated local leaders across the world.

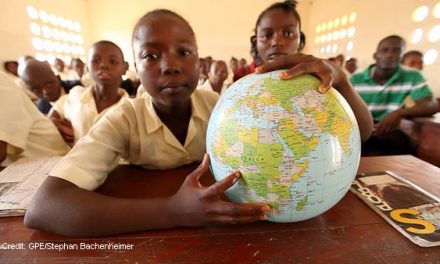

We’ve seen the impacts of a historic lack of investment in local leadership in the education sector. The focus of foreign aid has often been on the needed technical inputs – digital tools, curricula, or infrastructure – without equivalent investment in the leadership of those responsible for implementing them. In Uganda, for example, the 2000s saw a surge in donor support for Universal Primary Education (UPE), with heavy funding for access, facilities, and policy reform. But comparatively little was allocated to investing in building the leadership of headteachers, educators, district officers, and school management teams. As a result of the lack of such investments, absenteeism rose and learning outcomes stagnated. It wasn’t until the 2010s that this pattern began to shift. Programs like the Uganda Teacher and School Effectiveness Project (UTSEP) made deliberate investments in leadership development of headteachers and district capacity, leading to measurable improvements in teacher quality and early grade literacy. Yet even these gains were partial. The reforms reached only a subset of districts, and while teachers received support to strengthen instruction, they were largely excluded from leadership development efforts that could have supported their professional growth and deeper engagement in shaping system improvement. This challenge of sustaining and scaling gains is not unique to Uganda’s education sector; it is a recurring theme in development work where local leadership capacity is not systematically cultivated.

In the work happening across the Teach For All network, we’ve seen the benefits of long-term investment in recruiting and developing many more of a country’s most highly sought-after university graduates to invest themselves in teaching in under-resourced contexts. These two-year teaching commitments not only matter for students, they are foundational for a lifetime of leadership on the part of the teachers themselves, who become change agents working throughout education systems. Over and over, we have seen that when we build a critical mass of these leaders working at every level of the education system and also from the outside as innovators and advocates, the very culture as well as the practices and policies of the system begin to change.

The presence or absence of local leadership significantly influences whether development gains are sustained. It’s a truism that sustainable development cannot be imposed or outsourced. It must be led by those who are closest to the problems. What’s needed in our foreign aid system is a shift in both mindset and method: from funding short-term outputs to cultivating the capacity of people to lead system change over time.

As governments and philanthropy face the sudden dismantling of today’s foreign aid system, it should be a top priority to embed leadership development into their core strategies, investing in new leaders and those already working in systems, and treating agency as both the input and output of sustainable development.

As international aid patterns dramatically shift, national institutions, including the Ministries of Finance, can be supported by the donor community that is still active to recognise the catalytic power of relatively small, long-term investments in leadership development. Where governments have backed leadership development initiatives, we’ve seen the emergence of capable, locally-rooted leaders who drive systemic change from within. In Liberia, for example, which is facing a dramatic drop in funding due to USAID collapse, successive administrations in the last 15 years have supported an initiative started by former President HE Ellen Johnson Sirleaf’s government to rebuild a strong civil service in the country across all government departments. The President’s Young Professionals Program attracts the strongest graduates and top talent to rebuild the country. As a result, Liberia has strong public leadership in place to help weather the storm – like it did during the COVID-19 pandemic and the Ebola crisis too. The program has been so successful that it has grown into Emerging Public Leaders operating in Kenya, Ghana, Liberia, Malawi, and Sierra Leone, with 500+ young public leaders in more than 90 government departments. But this is just the start, as so much more needs to happen if we are to engage more young ethical and professional leaders in strengthening public institutions and building equitable public services for all.

Some philanthropists are already reconsidering their approaches. For those inspired to embrace ‘people-first’ approaches by investing in local leadership development within developing contexts, the People First Community offers a valuable framework and concrete examples. This cross-sectoral and globally-diverse group of practitioners, academics, and public and private sector actors has considered the shifts donors would need to make in order to foster such local leadership development:

- Donors must go beyond analysing “what works” to scale specific interventions. They should also invest in the people and networks who generate solutions from within, enabling local actors to lead, learn, and adapt over time.

- Rather than deciding which strategies to pursue and then finding grantees to implement them, more donors should invest in efforts that proximate leaders decide to prioritise and narrow thematic focus areas should be avoided.

- Donors must recognise the leadership that already exists within communities and invest in its development and visibility – including supporting leaders to raise and secure diverse funding that is longer term and more sustainable.

- Donors should continue to seek out change agents who are not high-profile, but are working deep within local, sub-national, and national systems–and have deep understanding of local contexts, resource issues, and challenges and solutions.

- Rather than pursuing short-term change and scalability, donors should take the long view–investing in the leadership development that will enable adaptive, long-term progress.

The unprecedented situation in which the international development community finds itself is a crisis, but with crisis comes the opportunity to reinvent and build back better. We can reshape funding systems to prioritise people and collective leadership. Philanthropic leaders and funding institutions that understand this shift, and are willing to back people and not only projects, will be instrumental in building adaptive, sustainable systems capable of navigating future uncertainties.