This blog was written by Kashfia Latafat, research scholar at Aga Khan University Institute for Educational Development.

Introduction

Language policy has a dominant role in designing educational outcomes and social mobility, specifically in multilingual developing countries. English, often adopted from the colonial period, continues to rule education sectors in developing nations. While English is broadly seen as an enabler to access global openings, its prominence in education often expands social inequality and marginalises speakers of indigenous languages. This literature review examines how language policy, particularly the highlighting of English, disturbs access to socioeconomic mobility in developing countries. Based on key theoretical frameworks and comparative case studies, it illustrates the tensions between global objectives and local realities.

Colonial legacy and the rise of English

The dominance of English in many developing countries is engrained in colonial history. During British rule, English was established as the language of governance, law and elite education. Post-independence, many countries adopted English to maintain administrative continuity and global application. In Pakistan, English remains the official language alongside Urdu, regardless of being spoken fluently by a small elite. India, as a nation without a national language, continues to use English as a comrade’s official language, and Nigeria has adopted English as the primary path of instruction and administration.

Phillipson defines this distinctiveness as linguistic imperialism, where English extends not just as a language but as a system of supremacy. Bourdieu adds that language functions as symbolic capital, giving English speakers an honored entrance to education, employment, and power. These frameworks supports the narrative of why English continues to hold such power in post-colonial societies. The examination of literature from the lens of the post-colonial era indicates towards a similar picture, which highlights English as a prominent language to be used by elite classes and acts as a gatekeeper for social and economic development.

English as an instrument for socioeconomic mobility

English expertise is widely observed as a trail to upward mobility. In Pakistan, English-medium schools are mostly associated with elite status and better career prospects. The Central Superior Services (CSS) exams, which define access into the civil service, are arranged in English, effectively eliminating candidates from non-English backgrounds. It highlights the supremacy of the English language over national and regional languages, where most opportunities are for the elite sector who can afford it. This develops an image of unfair practices in language policies, specifically in developing countries, where systems need to reduce inequalities by adopting inclusive and diverse approaches at both national and regional level.

India presents a similar picture, where English-medium institutions are associated with shining in the global economy. In emerging countries, education in dominant languages like English is powerfully associated with higher income and better career options.

In Nigeria, English is the language of instruction and administration. Recently, the Nigerian government announced a language policy for people which aims to unite a linguistically-diverse nation and improve the rate of literacy. Meanwhile, limited trained teachers and a lack of resources often handicaps children who speak indigenous languages at home. Students face difficulties in learning efficiently when taught in a language they do not know, preventing their academic performance and future openings.

Class-based educational divide

The prioritisation of English in education systems often supports existing class structures. In Pakistan, English-medium schools accommodate the elite, while public schools practice Urdu or regional languages. This double system creates an educational apartheid, where language becomes a marker of class and privilege.

India’s education system is likewise stratified. English-medium schools run more in urban areas and function for middle- and upper-class families. Public schools, which serve the ‘commoners’, are often deficient in qualified English teachers and resources. This gap spreads inequality, as students from deprived backgrounds are not capable of competing with their English-speaking peers. English in India today is an agent of decolonisation that enables the urban poor to access the global economy.

In Nigeria, the situation creates regional inequalities. While urban schools may have better English instruction, rural schools often face shortages of trained teachers and materials.

Access to English education creates further divisions in communities. In several developing countries, education systems are mainly divided along class lines. The elite can afford education at private schools with better resources, where instruction are given in English, and more global opportunities are waiting for them. While children from lower-class backgrounds are often restricted to underfunded public schools with limited resources. This gap leads to social inequality, making it harder for marginalised groups to break the cycle of poverty.

Cognitive and pedagogical challenges

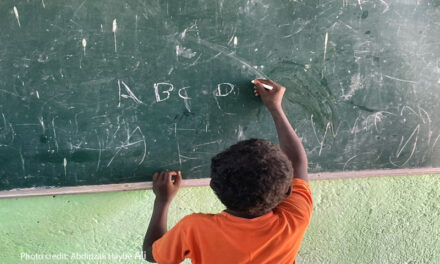

Teaching in English without proper support poses significant cognitive challenges. Research suggests that children perform better when instructions are given in their mother tongue, particularly in early year education. UNESCO states that improvement in learning outcomes is mainly because of teaching in native languages.

In Pakistan, learners in public schools often encounter difficulties with English instruction, leading to low comprehension and high drop-out rates. The emphasis on English creates a disconnection between students’ linguistic realities and the classroom environment. In Bangladesh, poor literacy and numeracy outcomes are also associated with early English instruction, specifically among children from non-English-speaking backgrounds.

These challenges in the area of pedagogy highlight the core idea of using English to promote socio- mobility. Instead of empowering students, English instruction without support can create further division in education and future prospects. Building on this perspective, English language should also be discussed in the context of its indispensability in social mobility and survival in Pakistan.

Policy versus practice: The implementation gap

While many governments endorse English for its apparent neutrality and global utility, there is often a gap between policy and practice. In Pakistan, the National Education Policy highlights English proficiency, but public schools have shortages of trained teachers, resources and inclusive pedagogy.

India’s Act of Right to Education dictates free and compulsory education, but overlooks the area of the language of instruction. As an end result, English-medium education remains unreachable to many. Without focused investment in teacher training and development of curriculum, English instruction will remain to benefit only the elite.

Nigeria’s universal core education policy supports English as the medium of instruction, but implementation is uneven. Rural schools mostly face scarcity of qualified teachers and materials, leading to poor learning outcomes. A more inclusive approach would be to identify the linguistic diversity of learners and promote mother tongue instruction in early education.

While education is often treated as the great equaliser, it can also support inequity if policies fail to address structural barriers. Current educational policies must reach beyond access and ensure quality, equity and continuity across groups.

Theoretical frameworks and critical perspectives

The literature on language policy and socioeconomic mobility is grounded in several key theoretical frameworks. Phillipson’s concept of linguistic imperialism identifies how English expands as a system of supremacy, designing education, media and governance in developing countries. Bourdieu’s theory of cultural capital explores how language proficiency functions as meaningful power, providing English speakers with privileged entry to resources and institutions.

Jacobson supports linguistic rights and mother tongue education as a way of endorsing equity and stabilising cultural diversity. She discusses that denying children the right to learn in their native language creates linguistic genocide, damaging both educational outcomes and identity formation.

These frameworks offer a critical lens for considering the complex connection between language, education and mobility. They challenge the notion that English is integrally empowering, and call for a more inclusive approach and context-sensitive language policies.

Conclusion

While studying the role of English in developing country contexts with a colonial past, findings clearly depict similarities. In Pakistan, English language in the education system restricts the entrance of marginalised communities. Further, English operates as both a tool for upward mobility and a gatekeeper for restricting entrance. A similar situation is visible in India, where English is used as a status symbol, and only the elite are eligible to reap the benefits. In Nigeria, the English introduced in colonial times still plays a dominant role in education and governance; creating a source of division in rural and urban settings. This similar pattern across postcolonial societies shows how English, while supporting contribution in global economies, also develops inequalities by sidelining indigenous languages.

To facilitate true socioeconomic mobility, policymakers must consider the implementation gap and support inclusive, multilingual education. This encompasses using mother tongue languages as the medium of instruction in early education, training teachers and developing culturally-relevant curricula. As the literature highlights, language policy is not just about developing connections, it is about power, identity and opportunity. Overall, the literature proposes that appreciating language as a global source, while protecting local languages, will ensure equitable access to education and opportunities.