Ample attention has been given to the educational participation levels and examination performance of girls relative to boys. Across much of the developing world, more boys than girls attend and complete general education. However, in countries where similar and high proportions of both boys and girls participate, the latter tend to out-perform the former. In this UKFIET Blog, Mike Douse proceeds beyond the stereotypes, delineates the crucial from the inconsequential, and suggests that disparities other than boys versus girls might now be more deserving of attention. Finally, the very acceptance of exam scores as a valid indication of educational success is questioned.

Boys outperformed girls in England and Wales top A-level grades in the summer of 2025, with 28.4% of boys scoring an A* or A, compared to 28.2% of their female classmates. This was unusual in that, over the decades, UK boys have consistently underperformed compared with girls across all age groups and nearly all ethnicities. It provoked headlines, editorials and much discussion until, two weeks later, the GCSE results were issued, showing that 70.5% of girls were awarded at least a Grade 4 compared with 64.3% of boys – normalcy was restored.

As this was occurring, a British Parliamentary Commission was exploring “why boys lag behind girls in education”. Their investigation indicated that:

- Boys were more than 1.5 times more likely to be suspended from schools than girls, and more than twice as likely to be permanently excluded.

- Some boys, such as those from the Caribbean, Gypsy/Roma or Traveller of Irish Heritage backgrounds, have particularly low attainment levels.

- Boys are also more likely than girls to have identified special educational needs.

The irony of a major enquiry reporting concurrently with the announcement of exam results in which boys performed marginally better than girls is not lost.

Across developing countries, a different picture has long prevailed, with far more boys than girls participating in and completing their schooling. Development agencies, non-government organisations and the countries themselves have addressed this disparity with considerable success. For example, using data from four of the countries in which the present author has worked (Bangladesh, Kenya, Nigeria and Pakistan), he calculates that, over three recent decades, the proportion of girls completing at least ten years of general education rose from, on average, 29% of the cohort to around 73%. Moreover, there is evidence from programme evaluations that educated mothers are highly likely to ensure that their daughters, as well as their sons, complete their schooling: the advances seem sustainable.

Nevertheless, the recent UNESCO Global Education Monitoring report reveals persistent gender disparities in education worldwide: “although 50 million more girls have been enrolled in school globally since 2015… there are 122 million girls still out-of-school… trapped in pockets of disadvantage due to location and poverty and other social and cultural characteristics”. Factors such as violence (approximately 60 million girls are sexually assaulted on their way to or at school every year), pregnancy and the associated stigma, and child marriage remain critical challenges. However, in those countries where similar and high proportions of both boys and girls participate, girls tend to out-perform boys.

It is suggested that a relevant factor here is the ‘feminisation of education’, linked with the long-time predominance of female teachers: women primary teachers outnumber men by roughly 5:1 (although men are disproportionately represented at senior levels such as Head Teachers). This, it is conjectured, “may give girls an advantage in terms of female role models, higher expectations for girls’ abilities and lower expectations of boys… School lessons may impose feminine qualities that male students cannot relate to… Girls have an advantage in coursework since they are more organised, conscientious… (and) the move from more individualised educational practices in the classroom to more collaborative and cooperative practices… (gives) girls an advantage over boys because they generally have stronger communication and collaborative skills” (ibid).

Conversely (and this is paradox territory), the curriculum has long been a repository of gender stereotypes. “Despite the patriarchal nature of the education system, women are hugely underrepresented in the curriculum, as men have historically dominated many fields and this is reflected in who is taught about. Even where schools do make efforts to include notable women in given fields, taken as a whole – across subjects and across year groups – men (and predominantly white men) still dominate, sending powerful messages to children…”. Related to this, and to gender stereotyping generally, until recently, higher proportions of boys than girls took STEM subjects (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) although this is changing, alongside the increased recognition of female scientists, software developers, medical researchers and various kinds of engineers.

In-school factors are also offered as explaining the gender gap in education with “teachers tending to see boys as unruly and disruptive… lower expectations of boys and so are less inclined to push them hard to achieve high standards… a black anti-school masculinity… pro-school female subcultures who actively encourage each other to study… laddish behaviour made students seem cool and thus popular… few boys were able to be both popular and academically successful… conscientious boys who tried hard at school were often labelled as feminine or gay…”. Some evidence-based actions aimed at overcoming discrimination and inequity in these areas have had some positive consequences.

Nevertheless, we are dealing here with reckless generalisations bordering upon dangerous stereotypes. Not all boys display laddish behaviour, not all girls encourage one another to study, not all teachers regard all boys as disruptive or those of Caribbean heritage as ‘anti-school’. Indeed, labelling those from Gypsy/Roma or Irish Traveller backgrounds as ‘low attainers’ might well be a self-fulfilling (and verging upon racist) prophecy. Undoubtedly, there is something in some of those claims but certainly not everything. Indeed, the implication in research contributions that every child is either a ‘boy’ or a ‘girl’ is itself currently contested: each of us is part-masculine and part-feminine. That, in Afghanistan, over four million girls are being deprived of their right to education beyond primary school” is an unquestionable challenge. That British boys, on average, tend to score marginally less than British girls at ‘A’ level, other than in STEM subjects, is – let us face it – of relatively minor practical significance.

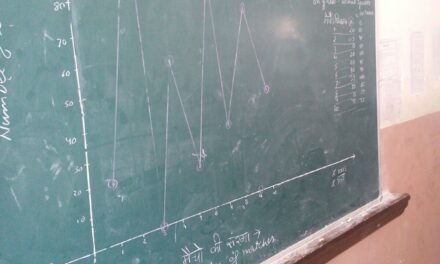

Moreover, examination performance related to, say, parental income, or geographical location (urban/rural), or of physical disability (“Deaf pupils achieve an entire GCSE grade less for sixth year running”), remains relatively unexplored. Indeed, the causes of vast differences in the performance of children in, say, Japan and Uzbekistan (PISA scores of 1,599 and 1,055 respectively), and the best strategies for responding to such gross international disparities, are virtually ignored. One instance of English and Welsh boys outperforming girls by a mere 0.2% (most probably due to more girls than boys actually taking the exam) provokes considerable media coverage and academic excitement. In that same exam, while 32.1% of students in London obtained top grades, only 22.9% of those in the North-East of England achieved the same – and this is calmly accepted. Perhaps it is time to concentrate less on Western world girls versus boys obscurities and focus seriously on other and more significant disparities.

Indeed, it may well be opportune to question the notion that exam performance is any use at all as an indicator of schooling success.