This blog was written by Dr Hélène Binesse, Research Associate, Research for Equitable Access and Learning (REAL) Centre at the University of Cambridge, and Dr Rui da Silva, Researcher / President, Centre of African Studies of the University of Porto.

Ensuring the quality of learning is paramount for every child’s development and success. Yet, in Africa, one in five children of primary-school age is not enrolled in formal school, and only one in five children reaches the minimum level of proficiency by the end of primary education.

Ensuring the quality of learning is paramount for every child’s development and success. Yet, in Africa, one in five children of primary-school age is not enrolled in formal school, and only one in five children reaches the minimum level of proficiency by the end of primary education.

As a means to addressing these poor learning outcomes in primary education, the global education community has placed a focus on Foundational Literacy and Numeracy (FLN). This focus is seen in part as a means to learn higher-order literacy and numeracy skills and access other part of the school curriculum. Some also recognise the importance of extending the concept of foundational learning to include socio-emotional skills. The use of the FLN concept is somewhat recent, promoted by multilateral organisations, some donor governments, and global philanthropic organisations.

To what extent are African researchers publishing on FLN?

In an ongoing project supported by Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, Education Sub Saharan Africa (ESSA) and the Research for Equitable Access and Learning (REAL) Centre are mapping educational research that evidences practices to improve FLN skills among children, and identify the extent to which it is prioritised in decision-making. The work is particularly interested in identifying publications authored by Africa-based researchers, and also includes searching for non-published or locally published studies through African Journals Online, institutional repositories and engagement with researchers in Ghana, Kenya, Senegal and Tanzania.

We have searched for terms related to literacy and numeracy skills together with practices that primary school-aged children develop in the education system, including school settings as well as through alternative pathways (such as complementary basic education programmes). Applying searches for relevant terms in Web of Science, Scopus and Dimensions for the years 2020-2022, we retrieved 313 publications.

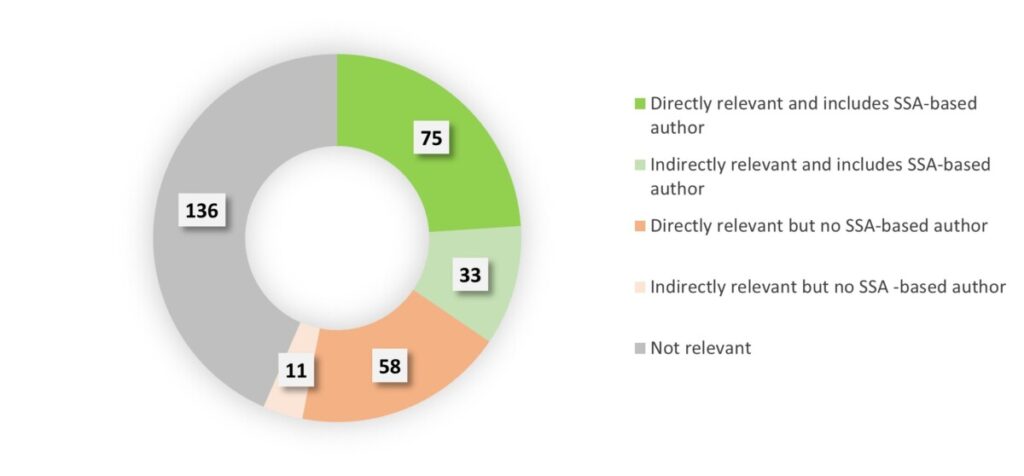

On closer inspection, 136 of the 313 publications are not relevant as they are beyond the scope of our focus. For example, they are related to early childhood education, not evidence-based or not about sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) . Out of the 177 relevant publications, 108 are authored or co-authored by SSA-based researchers (see figure 1). This is a relatively small number compared with 3,123 publications over the period 2020-2022 on education by SSA-based researchers identified in the African Education Research Database overall. A relative large proportion of these publications are on higher levels of education.

Of these 108 publications, 75 are directly relevant to FLN. For example, this study looking at the impacts of parental involvement on children’s performance in Zambia. The remaining 33 studies are identified as indirectly related to FLN. For instance, they focus on issues related to teacher training or language of instruction but do not directly refer to student learning outcomes and/or children’s engagement in literacy and numeracy activities, like this study on a digital literacy programme in Kenya.

Overall, these findings suggest that FLN publications are quite limited in the last few years. While we are also looking at earlier years, given the focus on FLN has been more recent (and so funding has also been more recent), we anticipate that this will not change the pattern considerably. This suggests that there is currently limited evidence which African governments can draw upon. Finally, all these publications are in English and, with the exception of Ethiopia, the studies are mostly based in countries with English as an official language such as Kenya, Ghana, Nigeria, Uganda and Tanzania.

Beyond publications in English

An important component of the project is searching for publications in French and Portuguese. To date, we have found fewer publications in these languages, in part because searching in these languages is much more challenging.

First of all, the so-called international databases (Dimensions, Scopus and Web of Science) used in the searches above host a very limited volume of non-Anglophone literature: about 95% of the publications are in English. In addition, the Francophone (CAIRN Info, Open Edition, HAL) and Portuguese (RECCAP, SciELO) databases available are mainly funded by higher education and research organisations or publishers. Unlike Dimensions, Scopus and Web of Science (which require a subscription), they are open access. However, the search engines are not sophisticated enough to undertake systematic literature searches.

Finally, translation of the keywords is not straightforward. For instance, equivalents of literacy in French could be alphabétisation, though it tends to be used more to refer to adult literacy and littératie is rarely used or often in relation to digital literacy or health. The same phenomenon is true in the Portuguese language, with an additional challenge regarding the use of European Portuguese or Brazilian Portuguese indistinctly.

Despite extensive attempts to search in Francophone and Portuguese databases for the wider time-period 2010-2023, we identified only 41 FLN publications in French and none in Portuguese. Of these 41 publications, 26 are authored or co-authored by a SSA-based researcher, and only 6 are directly relevant to FLN. This study, for instance, is investigating students’ linguistic needs in Burkina Faso. Through the in-country mapping of non-published or locally published studies in Senegal, 42 publications have been identified in total for the same time period. Of these, 15 are in English. This suggests that there could be more publications available in other languages than we find from searching online databases but that, even in Francophone countries, some of these might be in English.

Why language matters?

Publications written in English are more likely to be read and cited by the scientific community, encouraging the production of knowledge in English. Yet, monolingual research impacts not only on research productivity but also its content. Language barriers for non-native English speakers increase time and efforts in reading, writing in English and often dissuade them from presenting their research at international conferences run in English. In addition, English as lingua franca tends to sterilise the academic work, as multilingual scholars may adapt their language to be published.

The continued search for, and promotion of, publications in different languages is vital. Our point is not to promote French and Portuguese languages specifically, as there are many other languages of importance, but rather to underline English language dominance in the academic spaces. It questions the dissemination of knowledge, particularly in contexts where English is barely used. Research in languages other than English should be further supported to ensure diversity and equitable participation, as claimed by the Helsinki Initiative on multilingualism in scholarly communication. In addition, it could bring other scientific and language traditions and world views to the international and regional debates on educational research.

So whose responsibility is it – funders? governments? scientific journals? accessibility of search databases? researchers? Is translation one option? We do not have answers but the project attempts to address the issue by making non-English publications more visible.

———————–

This is the third in a series of blogs related to increasing the visibility of African research through the collaboration between Education Sub Saharan Africa and the REAL Centre, in order to increase the visibility and use of African research, with a focus on early childhood development and foundational literacy and numeracy. See also the African Education Research Database.

The first blogs in the series are:

Prioritising early learning research in sub-Saharan Africa for equitable learning outcomes