This blog was written by Jessica Oddy, Senior Research Associate at the University of Bristol, and Director of Design for Social Impact Lab, a social enterprise on a mission to redesign social impact work by supporting organisations, academia and practitioners centre equity in research, policies and programmes. It is based on a presentation given at the September 2023 UKFIET conference.

In October 2020, the Inter-Agency Network for Education in Emergencies (INEE), a renowned member network made up of many organisations that has established itself as an authoritative body in the field of Education in Emergencies (EiE) over the past two decades, issued a groundbreaking Anti-Racism and Racial Equity Statement. This statement was particularly significant given the limited attention paid to the influence of racial constructs and racism on individuals’ educational experiences within the EiE sector, where discussions surrounding racism are scarcely evident in advocacy, policy formulation, research endeavours, or program development. Consequently, the INEE statement signals a momentous call for transformative change within the field.

Recognising the need for change, as part of my PhD research that set out to explore forcibly displaced young people’s educational experiences in South Sudan, Jordan and the UK, I wanted to develop a critical EIE praxis.

Over a year, I spoke with 60 young people and 26 practitioners to explore educational experiences using Digital Storytelling Action Research (DSAR). Rooted in critical pedagogies and action research, DSAR created spaces for new knowledge forms to emerge, emphasising that individuals are not mere objects of inquiry but active participants.

- Systems Thinking- Inspired by the Black Radical Tradition

Our DSAR content drew inspiration from the Black Radical Tradition (BRT), a rich theoretical framework rooted in Black intellectual and political thought. The BRT offers critical insights into race, power, resistance, and liberation issues. Young people and practitioners highlighted how economic and power structures perpetuate educational inequalities during emergencies. The findings encourage us to interrogate how educational aid often reproduces and reinforces these structures rather than challenging them.

- Fosters multi-sited and challenges hostile bordering:

Doing multi-sited research online challenged hostile bordering environments, acknowledging that borders exist in geography, politics, subjectivity, and knowledge. While logistical constraints prevented a mixed-site cohort due to time zones and limited resources, we found a way to bridge the gaps. Co-researchers shared their findings across groups, fostering a sense of connection and global awareness.

- Amplifying forcibly displaced, racialised, and othered voices:

Intersectionality calls for a more nuanced understanding of the diverse needs and experiences of individuals and communities affected by crises. Participants had the freedom to design research questions, resulting in many sharing personal experiences of racial bias, cultural oppression, anti-Blackness, and discrimination. They discuss the intersectionality of their identities, highlighting the complex web of power dynamics they navigate within educational spaces.

- Iterative and mutual learning:

DSAR sessions became hubs of peer learning. Students shared their interpretations of key texts, audio, and videos, contributing diverse data as learning resources. The course itself was iterative, evolving with each cohort’s input. Co-analysis exercises and knowledge-sharing across sites redistributed methodological and analytical power, placing forcibly displaced youth as experts.

- Pedagogies of care and solidarity:

Critical participatory action research is not just about collecting data but about creating a care culture. In our DSAR project, we did not rush through the process. The project occurred during lockdowns in different regions, providing students with a meaningful way to engage when other opportunities were scarce. They supported each other, celebrated achievements and empathised with one another’s stories.

- Purpose for structural change and action:

DSAR transcends data collection and advocates for action and structural change. Young people explored how to use research findings to inform advocacy and policy changes.

What emerged from this method

There were many key findings (which you can read more about here). From using this approach, two things stood out.

1 ) Coloniality manifests in multiple ways

EiE interventions were often perceived as unjust by both EiE practitioners and forcibly displaced people, perpetuating exclusionary and discriminatory norms by design. For example, many practitioners noted that the sector was ‘based on a Western model’ that was ‘largely blind to racism.’ They noted examples of preferential treatment towards specific populations and how the sector had a ‘white saviour complex’. Young people shared examples of nationality-based scholarships, the reluctance of education stakeholders to address racism discrimination in schools and limited post-primary opportunities- which they perceived to be based on others’ perceptions of their capabilities.

2) People contest, challenge and devise alternative futures

Although practitioners were not as forthcoming with ideas to change the system, young people shared ample examples of how people were navigating delimiting educational opportunities. Whether it was creating schools in caves, moving to different camps across East Africa to access different schooling opportunities, volunteering, teaching, setting up organisations or taking courses online, people contest, challenge and devise alternative futures beyond the narrow parameters set by external stakeholders.

It also revealed that young people are not inert and waiting in camps for saviours; instead, many are forging their own better, envisioned future. Young people are not just aid recipients; they are aid providers.

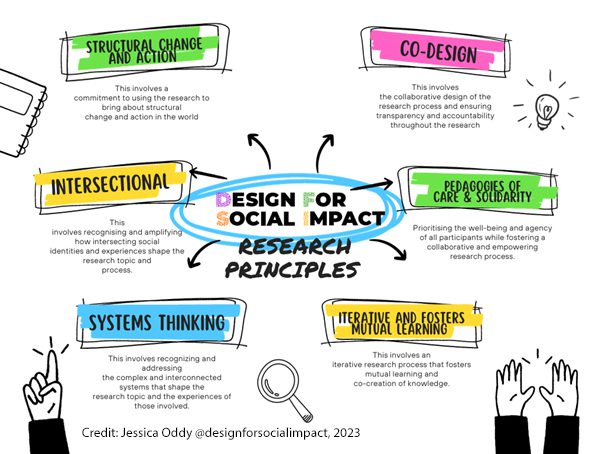

Using the DSAR model going forward

Revisiting EiE through the lens of the Black Radical Tradition offers a transformative perspective that challenges existing paradigms and demands a reevaluation of practices within the field. Applying the principles of the Black Radical Tradition to broader research, policy, and programme design work is essential for challenging existing power structures, amplifying those who have been structurally disadvantaged and historically underseverd, interrogating systems of oppression, promoting equity and justice, and fostering solidarity. We have built and adapted the DSAR principles at Design for Social Impact Lab and use them in the work we do with organisations, and practitioners who want to break away from entrenched systems of inequality and oppression that show up in research and social impact projects. You can click here to learn more (and receive a free handout with more details).