This blog was written by Sara Humphreys, Visiting Fellow, University of Sussex; Máiréad Dunne, Professor of Sociology and Education, University of Sussex; and Naureen Durrani, Professor, Graduate School of Education, Nazarbayev University. Co-authors of the study are: Jiddere Kaibo, Lecturer, Federal College of Education; and Yola and Swadchet Sankey, Education Specialist, UNICEF. This blog was originally published on The Conversation website on 21 January 2021.

Nigeria’s northern rural regions suffer acute shortages of both female teachers and female pupils. UNICEF estimates that over half of all girls are not in school in the north while under a third of all primary school teachers are women.

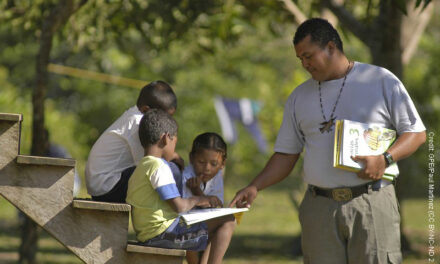

To boost the numbers of female teachers in rural locations, an ambitious scholarship scheme was established to train young women from these areas to become teachers in their home villages. It was hoped this would encourage more girls to enrol in school.

The Female Teacher Training Scholarship Scheme was a joint venture between five Nigerian state governments, the UK government and UNICEF, between 2008 and 2015. Scholarships were offered to young women from poor, rural areas to undertake the three-year pre-service teacher education programme at state teacher training colleges.

The only condition was that after graduation, they returned to their home village to teach for a minimum of two years. Over 7,800 young women benefited from these awards.

To help improve the programme’s operation, we conducted a study in the colleges of education in Bauchi and Niger states. As a team of Nigerian and UK based researchers, we identified the programme’s successes and challenges, and made recommendations for the future.

We found that there were both academic and other obstacles to the trainees’ success, including financial worries. This was because the scholarship stipend was too small and payments were often delayed.

Based on these findings, we suggest that improving the quality of teacher education is more important than just increasing teacher numbers. We also recommend that such programmes pay attention to non-academic difficulties.

Struggling to learn

Although it was claimed that all graduates were eventually given jobs in schools, in Bauchi and Niger states only 45% and 17% of trainees, respectively, managed to complete their training.

We explored the reasons for this low graduation rate, focusing on the trainees’ own experiences. Drawing on observations, a survey of 338 awardees and interviews with 49 awardees, 95 college staff and other stakeholders, we uncovered a range of factors that made it difficult for many of the young women to succeed.

The obstacles to success included overcrowded lecture halls, inadequate resources and a lack of support, such as study skills. The scholarship awardees identified numerous challenges, many of which were common to other trainee students not on the scheme. Colleges were struggling to cope with increasing numbers of trainee teachers. Dilapidated lecture halls designed for 400-600 students were crammed with two or three times that number.

Students often had nowhere to sit or take notes – assuming they could even hear or understand the lecturer. They had no opportunities to ask questions. High student numbers produced mounds of marking that overwhelmed lecturers. Some students were reportedly asked to mark papers on occasions. College libraries were short of relevant, good quality books and computer access was limited. Although learning materials were for sale, they were expensive.

The courses too were problematic. Trainees complained that they had little say in the subjects they studied, and that there was too much material to cover.

Learning in English was a major obstacle, which was hardly surprising given the awardees’ rural backgrounds and limited exposure to the language. These issues all contributed to their high rates of course failure and repetition, which in turn made it less likely that they would graduate.

The lack of practical course content was highlighted. Given the high student numbers, there were insufficient opportunities for practice teaching on peers. Teaching practice placement in schools also suffered from a shortage of lecturers to supervise it and lack of money to pay for transport.

Accounts from many of the scholarship students pointed to the need for study skills support, including remedial English, and more help from lecturers – who were often overwhelmed by student numbers.

Difficulties outside their studies

Apart from these academic challenges, issues like money, accommodation, transport, family and safety added to students’ difficulties. Almost half the awardees identified financial worries – in particular the inadequacy and late payment of their stipends – as the greatest threat to completing their studies. A shortage of on-campus accommodation meant many had to find lodgings elsewhere, spending most of their stipend on rent and travel to college. To save money, some trainees walked long distances, arriving at lectures tired or late. Travel also took time away from studying.

The quality of accommodation available came in for some criticism. And over a third of the trainees with children bemoaned the lack of health and childcare facilities.

Safety was a major concern in lodgings, or when travelling to and from the college. Interviewees recounted incidents of intimidation, robbery, sexual harassment and violence. In the survey, one in three complained of harassment by staff – such as sex for grades – or by their male peers.

Married women or women with children, on average, had higher rates of course failure and repetition than single women without children.

What we learned and what’s needed

The experiences of these students show that scholarships alone are not enough to increase the numbers of qualified women teachers. Indeed, the insufficient stipend and late payments added to recipients’ academic struggles.

Like similar studies, our research also highlighted how colleges of education in Nigeria are desperately in need of more resources – financial, physical and human – to improve the quality of training.

Extra academic support is required for disadvantaged students such as these young women, many of whom experienced poor quality schooling themselves. Improving quality in the colleges of education also means addressing gender-specific issues such as childcare services, secure accommodation and sexual harassment.