This blog was written by Professor Kwame Akyeampong, GEEAP member and Professor of International Education and Development, Faculty of Wellbeing, Education & Language Studies, The Open University; and Abelardo de Anda Casas, current DPhil in Economics at the University of Oxford and a member of St Hugh’s College.

In May 2023, the Global Education Evidence Advisory Panel (GEEAP) published its third report: 2023 Cost-Effective Approaches to Improve Global Learning, (often referred to as the ‘Smart Buys’ report), an update to its earlier 2020 ‘Smart Buys’ report.

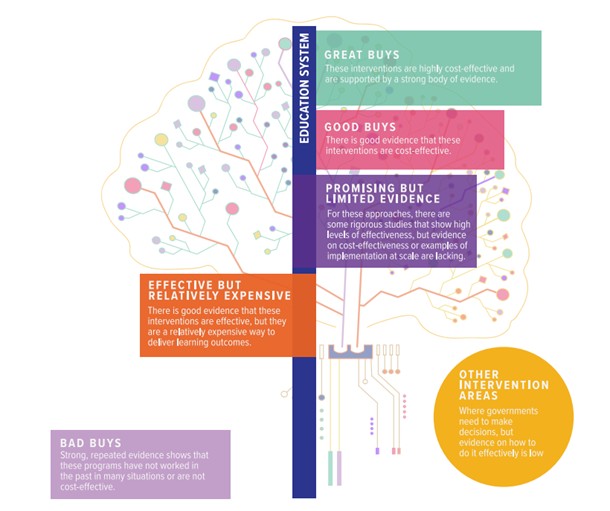

For this new report, the Panel, supported by a research team, carried out a systematic search of over 13,000 additional studies, leading to a total of over 400 high-quality evaluation studies being referenced in the report. These evaluations were reviewed based on various criteria—most notably, how cost-effective they were at improving learning and other outcomes, and whether they had been successfully implemented at scale. On the basis of this evidence, the Panel was able to develop its recommendations and classify interventions into five categories from ‘Great Buys’ to ‘Bad Buys’. (See Figure 1 which depicts the different intervention categories from the ‘Smart Buys’ report).

In this blog, we want to focus less on the Panel’s recommendations, but the challenges and gaps that we found – areas where additional research would be particularly useful. We want to highlight a few of them below.

One of the categories in the report refers to interventions that are promising, but for which limited evidence exists. The types of interventions include:

- Using software that allows personalised learning and adapts to the learning level of the child (where hardware is already in schools),

- Augmenting teaching teams with community-hired staff,

- Providing mass treatment for common health conditions including free glasses,

- Multi micronutrients, and preventative malaria treatment,

- Leveraging mobile phones to support learning,

- Safeguarding students from violence,

- Teaching socio-emotional and life skills,

- Involving communities in school management, and

- Targeting interventions towards girls.

For these interventions, there are some rigorous studies that show high effectiveness or cost-effectiveness, but either evidence on cost-effectiveness or evidence at scale is limited. An additional challenge is the lack of information about scaling of interventions. Projects implemented as pilots at a small scale may become much less cost-effective or less effective when scaled up to regional or national scale. In some cases, research has proven evidence of impact on other indicators, e.g. health outcomes or school attendance, but the evidence about effects on learning may be sparse. Since these interventions are implemented in many low- and middle-income countries, collecting more evidence on learning in these areas will be important to ensure that investment funds are spent optimally.

While the amount of evidence about ‘what works’ in education has definitely grown in the last decade or so, cost data is still mostly lacking for education interventions. Out of the selected over 400 studies for the Smart Buys report, only 96 have cost data. Very few donors collect cost data on projects or research they fund, and even fewer of them make it mandatory. Building Evidence in Education (BE2) has recognised the importance of cost data and has created guidance for donors and other organisations to encourage the collection of education cost data and increase consistency on how they are collected. While understanding ‘what works’ is definitely important, governments looking for solutions to education challenges need cost data to weigh how to invest scarce funds with the highest impact.

While the research team included multiple languages in the systematic search (e.g. English, Spanish, French, Portuguese), it became clear that English language resources are still dominant. Increasing the amount of local language research can also help with uptake of evidence by local policymakers. One strategy the team adopted to broaden the scope of the search was relying on databases that specifically compile research from low- and middle-income countries such as the Africa Education Research Database, or Africa Journals Online. Coupling these databases with others, such as ERIC or EconLit, allowed the team to cast a wide net and include context-relevant research. This helped the Panel nuance the recommendations and inform the contextual considerations that are highlighted throughout the report.

Although this report focuses on the impacts of specific interventions aimed at improving learning, interventions are not all that matters. To drive system-wide improvements in learning and make them sustainable over the long term, systemic reform is likely to be extremely important. However, evidence about the key conditions for successful system change are rare and highly contextually driven. Furthermore, a major element of systemic reform to achieve learning for all is realigning the curriculum, assessment, and examinations to ensure that the actual skill distribution in the entire student population is met. Education systems in many low- and middle-income countries focus on schooling that mostly benefit children from advantaged or elite backgrounds. However, if there is political appetite for systemic change, addressing the curriculum and learning standards head-on could be highly cost-effective and benefit all students and not a few. It is not possible to cost out this type of change in the way that other interventions are costed, and it does require new materials and retraining of teachers, which could involve considerable outlays; but given the impacts are felt by all students in the system, the cost per student is likely to be low.

Yet, even without systemic reform, interventions like the Great and Good Buys described above can still substantially improve outcomes for millions of children and youth. They have improved learning at scale, often in systems that are not yet well-aligned toward learning.

Filling the gaps requires contributions from the UKFIET and broader research community.

Adding to the evidence pool with local research in local languages will not only make the Panel’s recommendations stronger in future years but, above all, enable governments in low- and middle-income countries to contextualise what has worked in other countries and global recommendations with local data. The UKFIET community has an important role to play in this. The call is for researchers, policy makers and education practitioners to engage with the report in ways which improves policy to address the learning crisis in education and through new robust research fill gaps that the report highlights.