This article was written by Akanksha Bapna, Senior Research Fellow; Susan Nicolai, Director of Research; and Sam Wilson, Research Assistant; all with the EdTech Hub and based at the Overseas Development Institute (ODI).

The Covid-19 pandemic has changed the world in many ways – not least in education. The role of technology in learning has now become irreversible. However, successfully integrating education technology (EdTech) into education systems is non-trivial. Educational use of technology is extremely context-dependent, the pathways to implementation are convoluted, and scale and sustainability are not guaranteed. The EdTech Hub’s recent Systems Position Paper takes a look at some of this complexity and explores how to establish a holistic view of an EdTech ecosystem.

What existing frameworks do… and don’t

The thinking around the use of EdTech is currently organised, in part, through a series of EdTech frameworks that have been developed by different actors. While these frameworks provide a valuable bridge between theory and practice, helping implementers see the components and connections needed to make EdTech work, they have been developed for a range of disparate purposes. For example, frameworks like the SABER-ICT Framework that helps policymakers and governments map out the policy process of integrating EdTech in education operates at the macro level, whereas the TPACK framework is aimed at helping teachers use EdTech in their classrooms and operates at a meso or micro level.

In taking a closer look across these frameworks, we find that:

- Most EdTech frameworks are, by definition, theoretical rather than applied. They provide for ideal case EdTech scenarios and are developed from a particular perspective, i.e. government, developer, teacher, and are therefore limited in scope. They therefore don’t always fit realities on the ground in different contexts.

- Most frameworks focus on a limited aspect of the EdTech sector. We used the five levels of the Ecological Systems model developed by Bronfenbrenner (1994)[i] to classify the EdTech frameworks by the level of operation within the EdTech sector and found that while some frameworks focus on the macro-level picture of institutions and actors, others focus only on a micro-level view of EdTech. This poses a challenge for constructing a comprehensive view of the EdTech system.

- Lastly, EdTech frameworks usually take a linear approach to examining EdTech. As a result, they do not necessarily account for the complexity of technology and its integration into real contexts (Hamilton et al., 2016).

Towards a ‘systems approach’…

Despite the drawbacks, EdTech frameworks provide a valuable resource to understand EdTech. Their challenges, however, compel us to explore other ways of examining EdTech systems and the actors involved in ways that can be directly applied, be more comprehensive and build in complexity.

A systems approach, unlike traditional ways of isolating individual components of a system and examining them in detail, looks at the whole picture. It asserts that all the working parts within a system do not operate in isolation but influence each other in various ways, sometimes so complex that the whole is much more than the sum of its parts. It sees all the components as highly interconnected, and having a purpose. It values the ambiguity and the uncertainty of not having definite answers.

… via an EdTech network

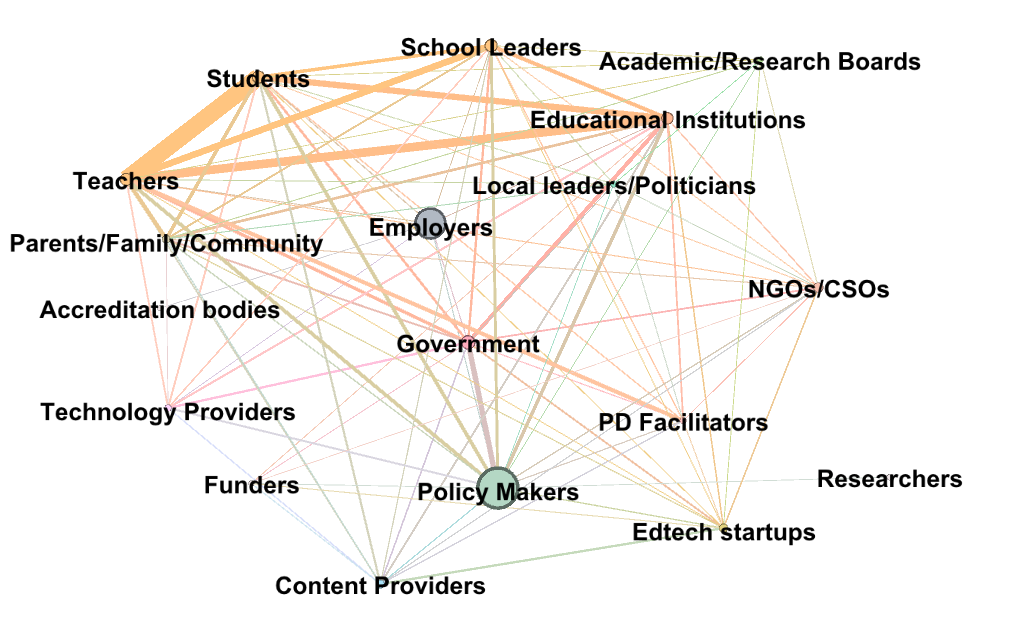

In the Systems Position Paper, we identified 17 EdTech frameworks that display a range of operationality from policy to research to implementation purposes and integrated them using network analysis. Analysis of these frameworks using systems approaches – and in this case Social Network Analysis (SNA) – leads to an understanding of the interconnectedness of the EdTech system and offers insights that were not evident using linear approaches. For example, visualising the network of EdTech stakeholders reinforces the idea that employers play a particularly prominent role in influencing the EdTech network. While it unsurprisingly highlighted the central role of policymakers in the network, it also questioned the role of researchers in influencing it.

New whiskers for old cats

A systems approach to EdTech and application of systems methodologies has the potential to add rigour to and strengthen analysis on the ground. For our work at the EdTech Hub, we are trying to better understand the key actors and how they interact in Sierra Leone, as it advances its education data usage, or in Tanzania, as plans are set out to use EdTech in teacher professional development.

Systems approaches have applications across many fields including management, evaluation and design, and can be of particular interest to researchers as they can add a huge repertoire of analytical tools to the research toolkit. As questions on EdTech use become increasingly important, systems approaches are crucial for gaining a holistic understanding of elements, interconnections and purpose.

[i] The model is composed of four layers of systems which interact in complex ways. A fifth dimension of time was added later . Johnson (2008) adapted the model for school systems (Johnson, 2008) and Gu et al. (2009) use a similar breakdown of the EdTech system based on Bronfenbrenner’s classification (Gu et al., 2019).

EdTech Hub, alongside INEE, will be hosting a symposium at the 2021 UKFIET conference called “Equity in Distance Education: Using EdTech to Improve Learning for All”, to discuss the INEE Distance Education concept note, and share key findings from our research into distance learning during COVID-19 responses. This will be held from 12.30-14.00 BST on Tuesday 14 September, and we hope to see you there.

List of EdTech frameworks

Macro-level EdTech frameworks (policymakers)

- The SABER-ICT Framework is primarily intended for policymakers and governments to aid their process of designing and assessing key policies linked to the use of ICT in K-12 education (Trucano, 2016).

- The UNESCO Framework provides policymakers with policy objectives to reform teacher capacity and professional development. It has been used to develop nationwide EdTech policies in Guyana, Bahrain and Russia. It can also be leveraged by teachers and teacher training experts (UNESCO, 2011).

- The Asian Development Bank Framework for policymakers provides guidance on establishing the coordination between policy direction and teacher capacity building along with a focus on infrastructure development, student learning outcomes, and private public partnerships (Asian Development Bank, 2017).

- The PISA ICT Framework gives a complete picture on students’ access to, and use of, technology as well as their learning outcomes. It also identifies how educational institutions and teachers incorporate technology into the classroom. Through this information, it allows policymakers to explore the influence of system level factors on students and schools’ use of ICT. It also helps nations and individual educational institutions understand their position in comparison to others (OECD, 2020).

- The Development Framework aims to help policymakers analyse the context in their country, develop suitable goals, and coordinate policies and programmes which lead to systemic change (Kozma, 2005).

Meso-level frameworks (educational institutions and heads of institutions)

- E-Learning Stakeholders’ Responsibility Matrix is responsible for e-learning and aims to ensure coordination amongst stakeholders. It is designed for higher educational institutions to understand, integrate, and adapt EdTech initiatives. It highlights that each stakeholder plays a key role by outlining their key motivations and concerns (Wagner et al., 2008).

- The Holistic Integration Framework guides educational institutions and provides them with a system to improve the evaluation of student learning and enhance the education system. It can be adapted to suit the needs of varied contexts (Khudair & Abdalla, 2016).

- ICT for Education (ICT4E) is a conceptual framework which contributes to the design of activities that lead to sustainable change in pedagogical practices in schools. It focuses on the integration of technology into teaching and learning (Rodríguez et al., 2012).

- The Framework for Stakeholder Inclusion helps the heads of institutions select inclusive technology and plan for its adoption by taking into account the considerations of students, teachers, and technology leaders (CoAction Learning Lab, 2019).

- The Organisation Improvement Plan (OIP) is envisioned as an approach for educational leaders to support teachers with the integration of technology into K-12 education. Its designed is based on a systems thinking approach (Chisholm, 2020).

Micro-level EdTech frameworks (teachers)

- The TPACK framework elaborates upon the knowledge a teacher requires to successfully incorporate technology into instruction. Its primary intended users are teachers but we hypothesise it could also be leveraged by teacher training experts (Mishra, 2019).

- The T3 framework promotes the use of EdTech by providing an actionable path for implementing EdTech and assessing the impact of innovative teaching and learning. It can be used by teachers to evaluate the use of EdTech in the classroom (Magana, 2020).

Multi-level EdTech frameworks (multi-stakeholder)

- The International Society for Technology in Education (ISTE) standards help teachers and education leaders ensure that learning is a learner-driven activity. It targets leaders, teachers, and students and aims to enhance implementation of technology and improve learning outcomes (Trust, 2018).

- The Framework for Evaluation Appropriateness of EdTech assists multiple stakeholders, such as teachers, educational institutions, technology providers, policymakers, and district / state level administrators. It helps in the planning and implementation of EdTech before and during the adoption of an EdTech initiative (Osterweil et al., 2016).

- Scaling Access and Impact is an ecosystem model which caters to government, stakeholders such as ministries of education, education innovations, and private philanthropic capital providers. It helps them understand their role in supporting access to and use of EdTech (Omidyar Network, 2019).

- The Adolescent Community of Engagement (ACE) Framework assists with the design and creation of adolescent online learning environments by building on four key constructs: student, teacher, peer, and parent engagement (Borup et al., 2014).