This blog was written by Maiya Hershey and Harry Haynes (British Council), and Ben Webster (Mosaik Education).

In dealing with refugee crises, an important but sometimes overlooked question revolves around how to improve access to higher education for people who have been forced to leave their home countries. As part of its education strategy, UNHCR is working with partners to make sure that 15% of refugees have a chance to accessing higher education by 2030.

There are currently over 6.7 million Syrian refugees worldwide. The majority of these displaced people live under emergency conditions that make it difficult and costly for them to access higher education.

Until now, many well-intended interventions aiming to support refugees entering higher education have often been top-down in nature – funders and development organisations assess the need and design scholarship and access programmes that are rolled out in affected communities. In some cases, interventions can miss important aspects of refugees realities – the need for income, the lack of transport, the need for childcare for example – and thus miss their intended target, are inaccessible to the intended beneficiaries and can suffer from large-scale drop-out.

Refugee Learning Ecosystems, a new report by Mosaik Education and the British Council, aims to introduce an approach to educational programming that, rather than working only with prestigious partners such as universities and ministries, leverages a range of informal learning spaces and actors, diversifies learning pathways and is learner-driven. The report is the result of participatory research with practitioners and refugee youth in Jordan and Lebanon, and it concludes with five key principles for taking a refugee learning ecosystem forward.

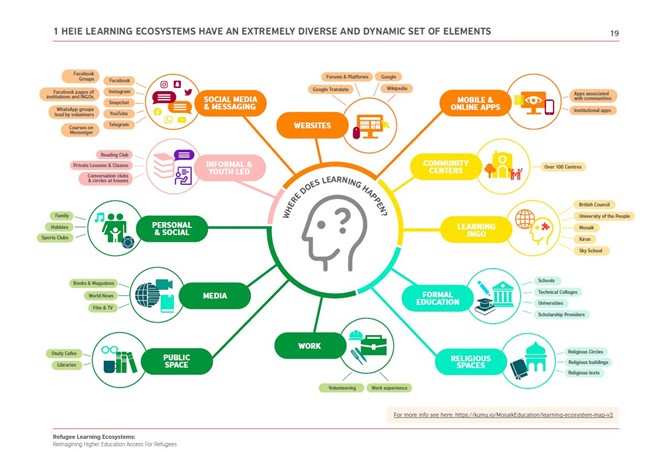

A ‘Learning Ecosystem’ can be defined as an open and evolving community of diverse providers that cater to the variety of learner needs in a given context or area, with a shared commitment to ‘minimise barriers and disadvantages faced by learners’.

Applying a Learning Ecosystems approach to refugee contexts could leverage a range of formal and informal learning spaces to surround these communities with knowledge made accessible in a multitude of forms including digital platforms, local community centres, communication tools, and local leaders acting as integrators and facilitators.

For example, community centres are established as community hubs to serve all people in a given area, and their infrastructure and connections can be used as a starting point for creating an effective refugee learning ecosystem. And with an array of online courses and digital platforms, students are still able to continue their courses even if their living conditions change.

This holistic approach diversifies learning pathways to broaden access to education and improves relevance to future careers of learners. The strengthening of education opportunities, in turn, creates positive feedback loops, where learners become teachers, facilitators, and social entrepreneurs. This further strengthens quality and access, whilst being inherently learner-driven, growing, iterating, and maturing with time.

One recommendation of the report is to start by identifying opportunities to create or support ‘integrators’ of learning ecosystems. These can include platforms, learning centres, community leaders that tie together diverse activities, create entry points and pathways, connect resources, increasing connections within an Ecosystem. As the density of these connections and interactions increases, it strengthens the learning ecosystem, creating a feedback loop that reinforces the strength of learning ecosystem and the quality of the education provision.

Whilst learning ecosystems do emerge within refugee communities, where there is a need to reach information and education pathways that are difficult to access, the report found that these learning ecosystems are small scale and immature. Interventions that create or support integrators can provide both directions and improvement in quality. However, refugees in these communities are the most significant parties in driving initiatives and creating connections to communities, and therefore need to be co-designing and leading these interventions.

With tens of millions of refugees living around the world, this concept offers a new learner-centric and participatory approach to improving the educational opportunities of people seeking to rebuild their professional and academic lives.

—————————————————————–

Following the publication of the report and the launch event panel discussion, Mosaik and the British Council are reaching out to other organisations that can help them develop refugee learning systems. Get in touch: harry.haynes@britishcouncil.org or ben@mosaik.ngo.

Download our most recent report here: https://bit.ly/3DcBeER

Watch the launch event and panel discussion here: https://bit.ly/2Wnc7hs