This blog was written by Janice Kim, Postdoctoral Research Associate and Pauline Rose, Director, REAL Centre, University of Cambridge. Pauline is also International Research Team Lead for the Ethiopia RISE programme. This blog is part of a series from the REAL Centre reflecting on the impacts of the current COVID-19 pandemic on research work on international education and development. It has also been published on the RISE programme website.

Mother and child at Megab Health Center. Hintalo Wajirat woreda, Tigray Region. UNICEF Ethiopia/2019/Mersha

The potential effects of COVID-19 on education systems are now being widely considered. With learning disrupted for more than 1.6 billion children and youth worldwide, the implications are likely to be huge. Yet pre-primary education is one area that is receiving less attention. This is a potentially serious neglect, recognising the importance of tackling disadvantage from the early years. Given that early childhood is a critical period in which a child’s foundations for lifelong success is laid, the threats to financial, physical, mental and social health of families caused by COVID-19 could possibly affect their children for the rest of their lives.

In Ethiopia, schools have been closed from 16 March 2020, and more than 26 million learners from over 47,000 schools are currently staying at home. This places at risk the improvements to date in Ethiopia’s education provision, which has experienced a rapid shift from an elite to the mass system in primary education over the past two decades, opening up opportunities to many who were previously excluded from access to education. Despite these improvements, around 1 in 4 children are at risk of dropping out in the first year of primary schooling, and nearly half of students are likely to fail to complete primary education. Student learning outcomes also remain very low: 90% of Grade 4 students in Ethiopia have not reached the basic reading proficiency level.

A sudden influx of young children into pre-primary education in Ethiopia

Recognising these challenges, in 2010, Ethiopia adopted a new policy framework for early childhood education, with the aim of ensuring that children from disadvantaged backgrounds in particular would be ready for primary school. With increased government involvement, the gross enrolment rate in pre-primary education surged from 4 to 46% over a six-year period. This focus is aligned with the increased attention to pre-primary education as a means to promote school readiness in the education Sustainable Development Goal (SDG4). In an emergency such as the current pandemic, young children from disadvantaged backgrounds are at particular risk: of being left unattended, exposed to the economic hardship of families, with lack of access to clean water and sanitation, adequate nutrition and health care, and stimulating nurturing environments. Extremely limited government resources had been allocated to pre-primary education prior to the crisis, reaching only around 3% of the total education budget, making an appropriate response in the current situation even more challenging.

How to reach young children with no distance learning for pre-primary?

The Ministry of Education in Ethiopia has been encouraging students to continue education from home. Primary school students are advised to follow radio lessons and read their textbooks at home, while secondary school students are advised to follow lessons that can be accessed through satellite TV. However, there is no such strategy for pre-primary school students, including those who are enrolled in O-Class, a one-year reception class for 6-year-olds attached to public primary school. This is not aligned with the Government’s ambition of ensuring pre-primary to be free, compulsory and part of the general education in the Education Sector Roadmap 2018-2030. As a priority, consideration needs to be given to how best to reach these children, for example whether the development of media lessons for pre-school-aged children and their families is feasible and appropriate.

To design an appropriate response and identify the best ways of reaching young children, evidence is needed on the extent to which families have access to audio or other media technologies at home. In this blog, we use household survey data from our World Bank-funded Early Learning Partnership (ELP) research in Ethiopia to explore which children have access to audio and mobile phones that might enable them to join distance learning during the uncertain period of school closures. These data were collected in November 2019 from 3,200 households with pre-school-aged children across seven regions of Ethiopia. We highlight wide inequalities by household wealth and urban-rural locations.

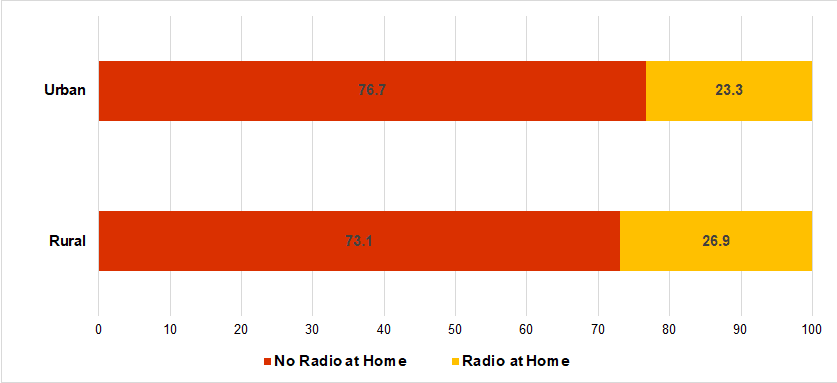

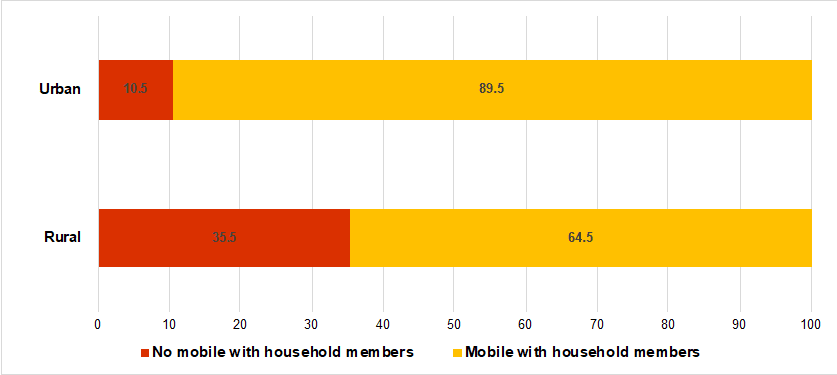

Access to radio is generally low and unequal between rich and poor households

According to 2016 Demographic and Health Survey data, the national average of radio ownership in Ethiopia is surprisingly low at 28%, far below the African average (54%). Our ELP data show a similar pattern, with only one quarter of the households having a radio at home. It is striking that there is low radio coverage in both rural and urban areas. The poorest are least likely to have access to a radio (18%). Even amongst the richest in the sample, fewer than one third have access (Figure 1). The overall picture raises a question about whether radio lessons can be the best way to reach young children during the time of school closures. Only 10% of households in Ethiopia, primarily in urban areas, have a TV at home, therefore it is highly unlikely that this can be an effective means of delivering education content to the vast majority of the population.

|

|

Figure 1. Radio ownership (%) in Ethiopia by location and by household wealth (ELP, 2019)

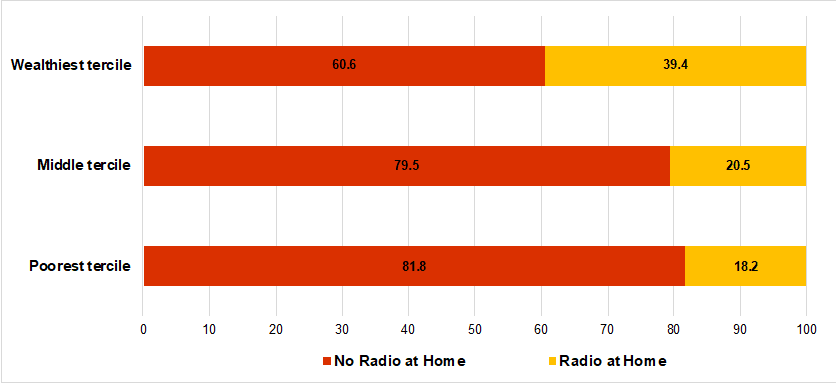

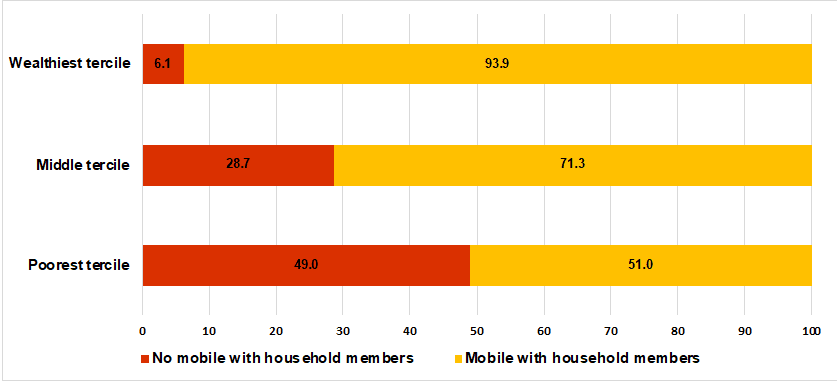

Access to mobile phones is more widespread, but with wider wealth inequalities

Another proposed way of communicating education material to households is via SMS or WhatsApp messaging, or the equivalent (such as Telegram, which is used in Ethiopia). Whether and how this can help support education for pre-school-aged children is one question. Another is whether there is sufficient coverage. Households are far more likely to have access to a mobile phone (around three quarters) than a radio (one quarter). However, inequalities are far starker: coverage is around half in rural areas compared with urban areas. Most wealthier households have a mobile phone, while only half of the poorest do (Figure 2). While distance learning using mobile technologies may have the potential to reach a wider population, it is not clear whether these mobile phones are sufficiently functional to exchange messages or media files through popular apps such as WhatsApp or Telegram.

|

|

Figure 2. Mobile phone ownership (%) by location and by household wealth (ELP, 2019)

Parents face multiple challenges in supporting learning at home

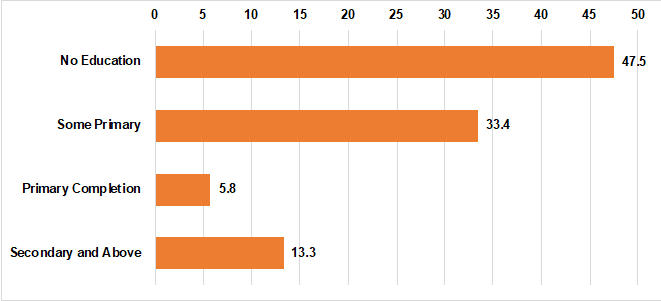

Even when radio or mobile lessons reach young children, they are unlikely to achieve developmental gains without sufficient support from their parents at home. Parents’ ability to support their children’s learning through the current intended media channels is highly dependent on whether they themselves have had any experience of schooling, or whether they can read. Among the primary caregivers in our survey, nearly half have never been to school and one third have not completed primary school (Figure 3). About half cannot read at all. Also, due to the economic recession as a result of COVID-19, parents from poor backgrounds often do not have the time and resources to support home-based learning. Approaches using media channels need to take account of these multiple constraints that families are facing, including identifying more creative solutions to enrich home-based learning, even for parents who are illiterate.

An urgent priority: handwashing facilities at schools

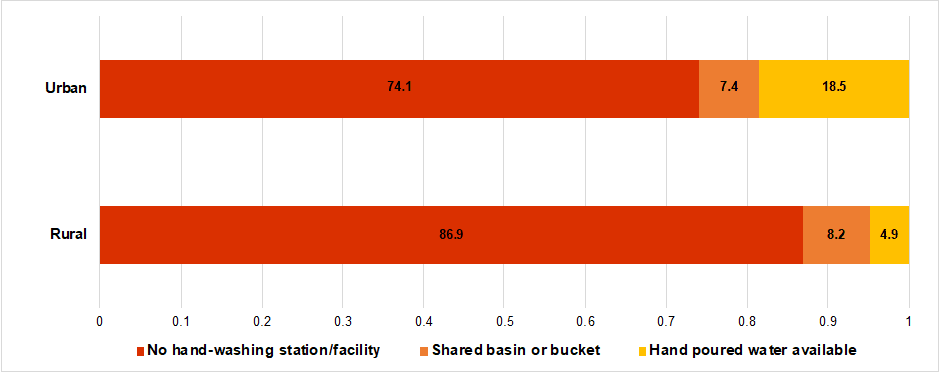

While it is important to ensure learning continuity during the crisis, one urgent priority will be to ensure handwashing facilities are available in schools when they reopen. Sadly, Ethiopia’s National Education Statistics show that only one in five schools had functional handwashing facilities in 2018/19. This is consistent with our household survey data, which further reveal that 74% of schools in urban areas and 87% in rural areas do not have any handwashing facilities. The remaining schools use a shared basin or hand-poured water, which may not be of sufficient standard needed to prevent the virus spreading (Figure 4). This striking figure is prevalent not only in Ethiopia but in other low-income countries: UNICEF report finds that only 13% of schools have access to handwashing facilities in 21 Eastern and Southern Africa countries. Without hygiene preparedness of schools, reopening could be dangerous for children spreading the virus and for teachers catching it. Equipping schools with handwashing facilities needs to be an urgent priority of multi-sectoral efforts with ongoing national programmes, such as One WASH National Program and Rural Productive Safety Net programme.

What should be the next steps to ensuring educational continuity during and after the pandemic?

- Develop effective distant learning strategies for pre-primary students by empowering parents

The Government’s efforts to ensuring learning continuity for all children should not overlook pre-primary education children. One promising approach will be unlocking the potential for parents to support their children’s learning. This needs guidance to be provided to parents on how to stimulate, play, and communicate with their children in age-appropriate ways. Ethiopia has some resources from recently-developed curriculum materials for O-Class, including local songs, stories and indoor games for young children, that can be easily adapted to audio or other media forms. Also, the global and regional Early Childhood Development Networks have been compiling useful resources for families with young children. Early Childhood Development Action Network (ECDAN) provides early childhood focused COVID-19 resources for parents, educators, and policymakers available in multiple languages. The Africa Early Childhood Network (AfECN) and the Asia-Pacific Regional Network for Early Childhood (ARNEC) are consolidating regional actions and resources for children and families amidst COVID-19. Approaches need to take into account the literacy level of parents, as well as their time constraints.

- Seek multiple media channels to reach children who are most vulnerable

In many low-income countries, distance learning using TV and radio is deemed to be a feasible option. Our data from Ethiopia point to access to radio being low, and so maybe not a solution for many. The widespread availability of mobile phones may open up opportunities to support parents to stay connected with teachers and communities for home schooling, although many obstacles remain (e.g. mobile connectivity, functionality and electricity) to develop this as one main channel for distance learning at a larger scale. In addition, ways in which this medium can be used in appropriate ways for young children’s learning deserves further consideration.

It is important for governments and donors to be informed by such data as presented in this blog, in order to adapt to the COVID-19 pandemic and develop strategies that are timely and relevant. Our ongoing project, the World Bank-funded Early Learning Partnership programme in Ethiopia, is keen to adapt research for the new reality in the face of a global crisis. We have worked together to identify how we can collect data that could be informative for policymakers, in real time through a mobile phone survey (recognising that this might limit participation of some, as indicated above). We hope to see how the Government is prioritising pre-primary education in their response to COVID-19, how parents are engaging in their children’s learning at home, whether any measures are being taken to avoid the pandemic further exacerbating inequalities, and how decisions to reopen schools are formed at system and household level. We hope the voices collected through the phone surveys will help us to inform the Government and donors to identify equitable and effective solutions for young children and families during and after school closures amidst the global crisis.

Thank you Janice Kim and Pauline Rose for this really insightful blog. I believe there are many possibilities to empower parents at the rural areas. For example, it is possible to collaborate with health and agriculture extension workers who are fully engaged at the grassroot level with households. It should be possible to arrange a quick training to those extension workers so that they provide some orientation to parents on how to support their pre-primary school children at home. The “child to child” support program can also be a potential way to reach the kids. We have now many secondary school and university students who are based in rural areas. They can be guided to do the job when it comes to supporting those poor kids in the rural areas. I think there are really many ways to support those pre-primary kids if there is the determination by the MoE and regional education bureaus.

Andargachew Moges, Department of Psychology, Bahir Dar University, Ethiopia.

Dear Andargachew,

Thank you very much for sharing your insightful thoughts on how to empower parents in rural areas.

Your points are really important as it will utilize the existing local, grassroots-level resources. Collaboration with health and agriculture extension workers for early childhood education has been discussed even before COVID-19 (but not realized), and this is a timely opportunity to use this collaboration to reach children in rural areas. Child to child model will also provide a good platform to engage many secondary or university students in young children’s learning as local volunteers. As you point out, it is very important to utilize local workers and volunteers who are willing to support children’s learning to ensure learning continuity during the school closures.

Thank you Janice Kim and Pauline Rose for your wonderful concern about early childhood education in Ethiopia during and after the pandemic. Using technology such as TV and mobile may be helpful for older children who are at primary and secondary education level. Beside the feasibility questions mentioned in the blog, using such technologies for younger children, have developmental disadvantages. Thus, it is better to think other options and the following may work.

Option 1. For educated parents who live both in rural and urban setting, parents could take responsibility of teaching their children. In this approach, the role of the preschool teachers and directors will be

1. designing age appropriate educational activities based on the preschool curriculum(resource materials developed by UNICEF);

2. giving the activities to parents with guidelines so that parents can facilitate and support their kids learning and

3. Doing follow-up using telephone. (Providing free call for teachers and parents can make this activity feasible and could be done by the government in cooperation with telecom service providers).

Option 2: For non educated rural and urban family children, family based child to child approach may work. In this approach, the older children who may be junior school, high school or university students take the responsibility of facilitating kids’ learning. The role of the director and preschool teachers is the same as those in option 1.

Option 3: For younger children who have no educated family and / or educated older brothers/ or sisters neighbor-family based child to child approach. In this approach neighbor older children who may be junior school, high school or university students take the responsibility of facilitating kids’ learning with the supervision of family members (mother or father or one of the guardians). The family supervision is crucial for preventing the pandemic and protecting kids. The role of the director and preschool teachers is the same as option 1.

In all options the learning time could be scheduled by the preschool teacher in collaboration with parents. The learning could be conducted on a daily basis, or in holidays and weekends depending on the lifestyle of the family.

After the pandemic, prevention mechanisms specially hand washing should be continued. So, strengthening the awareness creation activities at school and family level and using portable water tanker and hand wash facilities will be mandatory. However, this may not be the long term solution. Many researchers in this arena mentioned that ECCE in Ethiopia is practiced in an environment which is below standard (please refer one of the studies on ECCE practice on Bahir Dar Journal of Education volume 19, No 2: https://journals.bdu.edu.et/index.php/bje/issue/view/41/showToc). So the long term solution for this and other quality problems is making the preschools to the standard. This is the time to transform preschools in Ethiopia.

Thank you again.

Tiruwork Tamiru

Bahir Dar University, Collage of Education and Behavioral Sciences, Department of Psychology, Bahir Dar, Ethiopia

Dear Tiruwork,

Many thanks for sharing your insights on the critical issues and practical ways to address it.

Three options you listed by parents’ education level are a great way to explore customized support for young children through support from headteachers, teachers, parents, and communities. If there is any good example of Child to Child model after the pandemic in Bahir Dar, please feel free to share it with us. In terms of preschool curriculum, MoE/REBs have distributed revised curriculum materials (teacher guides and six activity books) since 2019, which also include resource materials developed by UNICEF. I will reach out to you in case if you need further information on this.

I sincerely appreciate you sharing your article on ECCE practice in Bahir Dar. Thank you very much.

I realise this is tardy, but CHILD to CHILD has revised its early learning materials in2020. You can find them on childtochild.org.uk/resources/ where you will also find new material on COVID 19 for Active Child Participation, including feelings, keeping girls safe, keeping healthy and happy. I am sure that those communities who have implemented CtC in the past (and there are many region which implemented the approach) would appreciate the COVID Material also. We are seeking funding to digitise them but they were designed for printing.

There is however a need to support the REBs and communities. Why not build on what was a very successful approach to reach those who need it? It had the added benefit of increasing the self esteem and skills of the older children who took part. Do get in touch if we can help. S.durston@childtochild.org.uk