This blog was written by Nomisha Kurian, Tanvi Sethi and Angana Das (more details at end). This blog is part of a series from the REAL Centre reflecting on the impacts of the current COVID-19 pandemic on research work on international education and development.

“Educating the mind without educating the heart is no education at all.” Aristotle

UNESCO suggests that a total of 1.54 billion students have been affected by the indefinite closure of schools and colleges. As children in India face unprecedented stressors, this seems a timely moment to consider their wellbeing. In this article, we highlight factors that threaten their emotional health and suggest measures to protect and nurture it; we discuss our experiences and insights as graduate researchers and development practitioners within India’s complex social, cultural, and economic milieu. Our analysis operates at three levels: society, home, and school.

SOCIETY: Keeping children safe

SOCIETY: Keeping children safe

Prioritising children’s wellbeing necessitates addressing both physical harm (direct violence) and structural exploitation (indirect violence). By the 11th day of the lockdown, India’s Childline helpline received 92,000 SOS calls. From 20th March 2020 to 10th April 2020, Childline experienced a 50 per cent increase in calls to 460,000 calls and led 9,385 interventions. Children’s concerns included protection against abuse and violence (30% of calls) physical welfare (11% of calls), child labour (8%), going missing (8%) and homelessness (5%) as well as child marriage, trafficking and abandonment.

Tackling both direct and indirect violence is necessary. One step could be to recognise intersectionality, or how different layers of identity (gender, class, caste, locality, etc.) produce overlapping vulnerabilities. For example, girls from low-income families may be doubly at risk of child marriage due to social norms undermining girls’ agency and the new economic pressures of job losses. We can also view child wellbeing and family wellbeing as interconnected; for example, children’s exposure to domestic violence in lockdown links to the new tensions experienced by adults (such as weakened social support networks). Along with inter-generational wellbeing, another step towards violence prevention might be to increase state funding for social protection policies and non-governmental work. For example, Childline has prevented no less than 898 child marriages since the lockdown. Therefore, it would help to declare the helpline an essential service and call for state attention to the complex socio-cultural and economic factors driving direct and indirect forms of violence.

HOME: Evolving home environment

Throughout child development, positive parent-child interactions at home contribute to academic achievement and self-regulation in children. Together, school and home develop children’s attitudes and social-emotional competence. With the lockdown, the home environment has come to the forefront. About 250 million school students are impacted as over 1.5 million educational centres are shut in India, severely affecting female learners. The disrupted school-going routine has made support groups like compassionate teachers, peer-mentor associations, activity-based groups, or sports teams dysfunctional. For some students, it may be a lack of complementary educational resources, whereas, for others, it is a deprivation of academic education and social isolation. Additionally, they are experiencing fear, anxiety, and the economic strain that some parents are trying to cope with. Indeed, there is no break from the monotonous, restrictive home environment – away from friends, nature, and society.

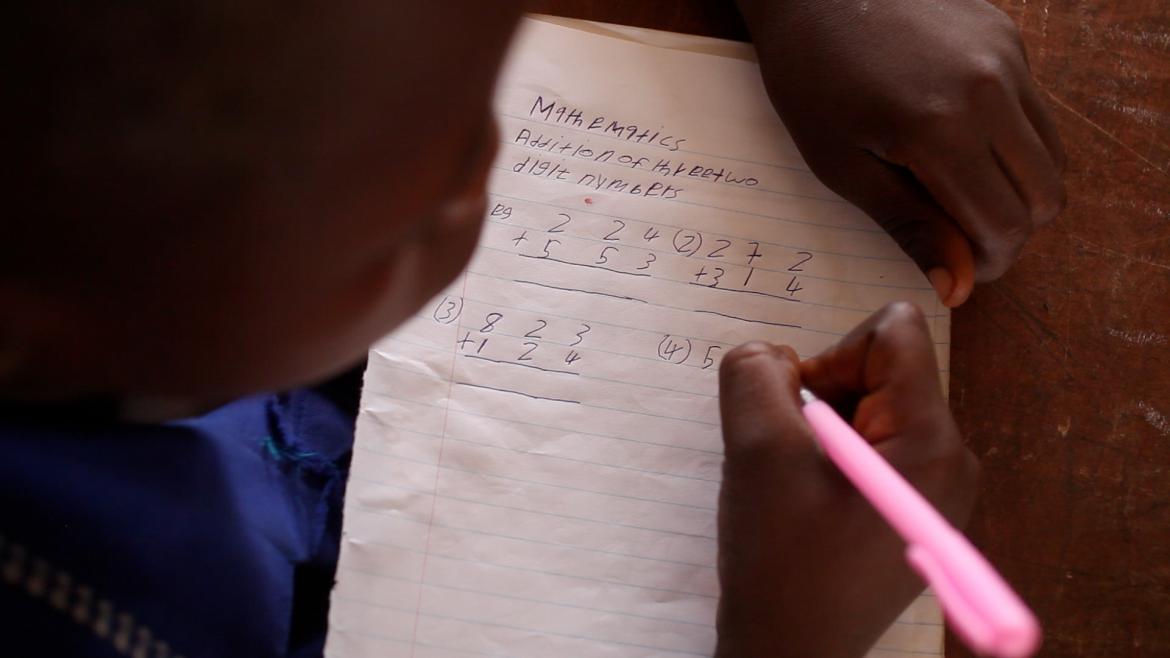

Unlike sanitised school environments, home environments vary. While schools solely cater to children’s essential needs, homes are most often not child-centric due to the pressing needs of other members of the household. Different economic strata impact children differently, which schools universalise, unlike homes. For instance, in lower-income households, children’s education and mental health are a lesser priority in the face of more pressing issues of economic survival.

Homes must be remodelled as fit learning environments for children, where skills of empathy, mindfulness, compassion, and critical inquiry are nurtured with familial love. Projects like Vatsalya (working with under-resourced communities on mother-child relationships for full-time students of government/public schools)have displayed improved results in mother-child relationships in semi-urban communities of Delhi, India. It is imperative to bring shifts in policies and practices to promote the accountability of homes. It has now become critical to align education with the changing social-emotional needs of children, now that ‘normal’ has been redefined.

SCHOOL: Making children happy

In response to the COVID-19 crisis, the Delhi government launched ‘Parenting in the Time of Corona’. This indeed was a timely response to an unprecedented challenge – How can we emotionally support children who are confined to their homes? As part of this initiative, the famous “Happiness classes” are now being conducted remotely. Teachers regularly upload stories on social media platforms such as YouTube and Facebook which start and end with mindfulness. These stories are open-ended and encourage reflection and discussion among parents and children in their homes. Also, parents and children receive daily happiness activities through text messages and voice response (IVR) calls.

The focus on children’s happiness can contribute to their wellbeing in many ways: Firstly, children gain a sense of belonging. It is reassuring for them to feel that teachers are concerned about their happiness and not just their academic performance. Secondly, it encourages children to think and engage creatively with one topic every day. This can help them develop a sense of purpose in shaping the new normal in the post-corona world. Lastly, it provides parents and students an opportunity to reflect together, which strengthens their bond. It transmits the belief that our emotions impact the decisions we make in life.

This pandemic has brought home the realisation that cognitive skills and academic competencies are insufficient while dealing with persisting unforeseen challenges. Teaching kindness, empathy, gratitude, and compassion in schools is of grave importance today. When schools reopen, children may have unanswered questions. Such initiatives can create a space for children to be themselves and express their emotions.

Conclusion

Now is the time to respond to unprecedented pressures on children’s wellbeing that may influence their social-emotional development in their growing years. The new stressors due to the pandemic put children at increased risk of abuse, violence, and exploitation, making safeguarding their wellbeing a priority. Moreover, while schools are shut and governments devise solutions, homes must be equipped as positive learning environments for children to flourish. The increased interaction time with parents during the lockdown can improve self-management and awareness, develop responsible decision-making, and promote prosocial skills in children, for they will remember this period as a significant phase in their developing years.

About the authors

Nomisha Kurian is a PhD candidate at the Research for Equitable Access and Learning (REAL) Centre at the University of Cambridge (researching child wellbeing in settings of violence and poverty) and a former Henry Fellow at Yale University (researching children’s rights). Her past work on building safe and inclusive schools, especially for vulnerable or marginalised learners, has most recently been published in the International Journal of Human Rights, the Journal of Peace Education and the Palgrave Handbook of Citizenship and Education.

With over 4 years of experience in education and development, Tanvi Sethi is pursuing her interest in early childhood development and social-emotional learning as a Commonwealth Scholar at the University of Oxford through the MSc Education (Child Development and Education) programme. She holds a bachelor’s degree with distinction in Psychology and Sociology from University of Delhi. As a Teach For India fellow, she taught first generation English learners in under-resourced classrooms. She is currently studying the impact of parenting and home environments on children’s social-emotional skills.

Angana Das is an MPhil student at the University of Cambridge Faculty of Education and a Commonwealth Shared Cambridge Scholar. Her MPhil dissertation focuses on teachers’ narratives of happiness and education in New Delhi, India. Prior to her MPhil, she has worked as a researcher on projects related to Right to Education 12(1)(c), remedial teaching and school leadership in India. She has also researched the role of arts-based approaches such as theatre, music and arts education in the creative transformation of conflict.

A well-written article, especially as it provides a perspective on Indian education through the current situation. Project Vatsalya is quite interesting to learn about. All the best for it. Cheers.

Thank you, Susan! As the co-founder of the project, I’d be happy to discuss it further with you.

I was looking for this information relating to the new normal prioritising child wellbeing in India. You have really eased my work, loved your writing skill as well. Please keep sharing more!