With the ‘COVID-19 Interviews’, NISSEM has embarked on a series of interviews with actors from government and civil society, in order to understand better the practicalities and implications of national responses to the COVID-19 pandemic. The focus is on countries in the global south. A full transcript of this Ugandan interview can be found here. NISSEM expects to continue this series of interviews for some months to come, as systems emerging from the crisis rethink the content and practice of teaching and learning. UKFIET is co-hosting the first five of these interviews.

|

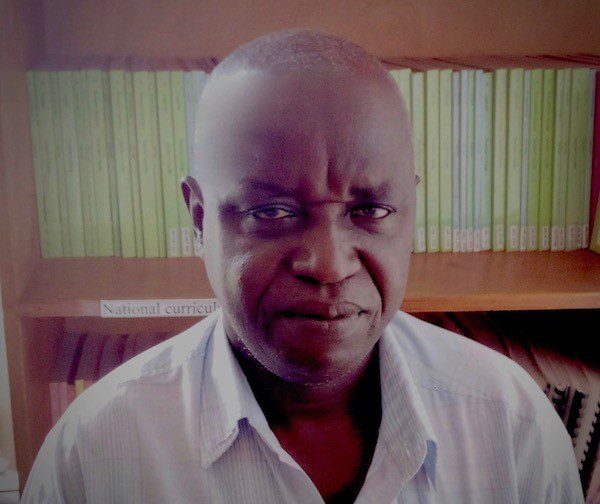

Baale Remegious is an experienced mathematics teacher and senior curriculum developer at the National Curriculum Development Centre (NCDC) in Kampala. He holds a Master’s degree in Mathematics as well as post-graduate diplomas in Education and Curriculum Design. At the NCDC, he has been involved in the development of Uganda’s lower primary Thematic Curriculum and also developed mathematics syllabuses for lower and upper secondary schools. Currently, he is involved in reforming the curriculum for lower secondary schools. |

Stakeholders are saying: “We need to have all those social issues in our education system. Let us not just go back to that academic thing only.”

Governments across the world had to move fast in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. In Uganda, the National Curriculum Development Centre (NCDC) was tasked with rapidly developing printed resources to be distributed to children for the immediate months. At the same time, private sector media companies began to produce their own materials and broadcast them through radio and TV. NCDC followed with its own radio and TV content, but with little experience in this medium. “Some radio stations and TV stations went ahead and developed their own content and started broadcasting”, Baale reports. “So, by the time we came in as government, some people had already gone on to use some of those materials.”

NCDC faced several challenges. The first was to know where the students were, after the lockdown was introduced. Some students remained in their hostels, while others managed to get home. “We have learners who attend boarding schools, but when they were told to go back home you couldn’t know where they were from. It was very difficult to know how many learners were in any particular locality”, Baale stated.

Lack of clear information was a major challenge for NCDC in delivering materials to the communities. “The district headquarters are urban centres. So, by the time they distribute to the rural areas the copies are not enough. Some stakeholders said, ‘No, go back with your materials until you get enough copies, then bring them to us.’ So that’s why some have not yet seen them.”

The printed materials – in a context of very limited availability of regular textbooks and other printed materials – became a tradeable commodity, with the result that the Ministry of Education announced that measures would be taken against profiteers.

Even radio and TV were not able to reach all communities: “Even for the national TV, upcountry, some can’t receive it.” Nevertheless, for urban centres, TV was one of the most appreciated measures. “I would say the one which has worked better than the others is the television for the urban centres.” He added, “The kids at home, they will tell you, ‘Oh, today, there is this lesson.’ So, they go to the TV. And it’s the same group, unfortunately, which has also benefited from the print materials because they are just at the headquarters of each district. For the rural, I would say we have not yet got the impact there.”

When Baale attempted a personal solution, he faced a barrier. “Somebody called me and said that for the whole sub-county, which may have a population of over 100,000 families, they had got only two copies for primary 2. So, I got concerned and I requested, ‘Tell me the number of primary 7 candidates, senior 4 candidates, and senior 6 candidates in our location, and I’m going to use my personal money and effort to print these materials and send them directly to you.’ I can tell you, up to now, they have not yet given me those figures. But when I researched why they have not sent them, someone told me that it is the same group which has taken these materials to the photocopier, so that now, someone has to buy them. Because now, if I take the free copies, there’s no business.”

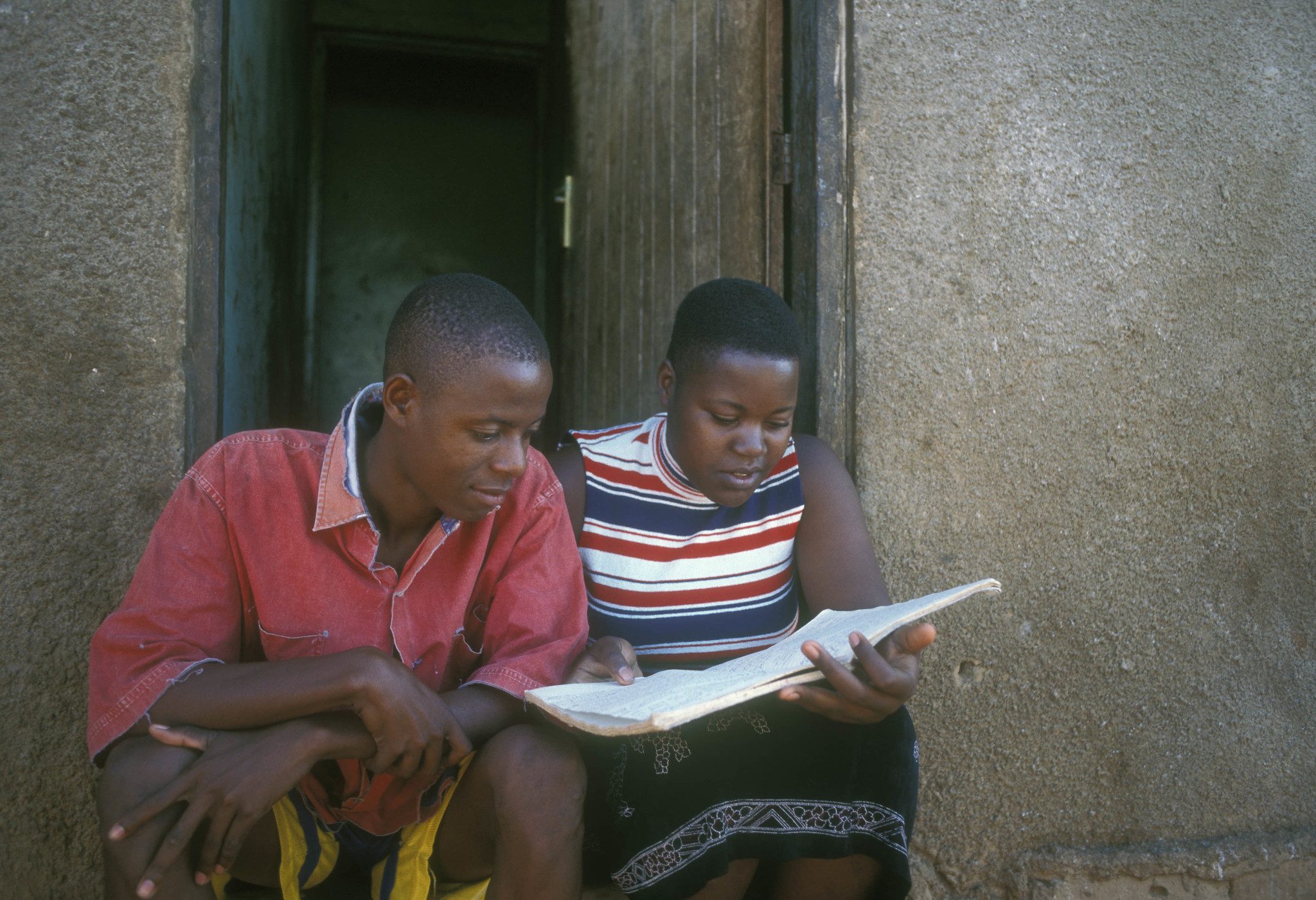

It is notable that teachers were effectively bypassed in the Government’s rapid response to the emergency. The emergency exposed the challenges of Uganda’s local language policy in lower primary grades, where textbooks have been a long-standing challenge. As a result, NCDC chose to take the quickest route available, which was to provide the printed materials in English.

By the end of May, the Ministry of Education was beginning to take stock. Logistical issues were not the only theme. Some stakeholders were now saying “We need to have all those social issues in our education system. Let us not just go back to that academic thing only.” At the same time, they were planning for the future, in whatever form it might take.

As in many countries, it is the parents who make the ultimate decision about returning to school despite COVID-19. In Baale’s words, “Although we have told these people who have examinations to go back to school, the parents are not willing because now they’re saying … ‘We should assume that it is the worst situation, we are in war. If there is a war in the country, what do you do?’”

This is part of a series of NISSEM COVID-19 Interviews. The series includes:

Responding to Covid-19 in Kenya: Interview with Lucy Maina and Ngángá Kibandi

Responding to COVID-19 in Lebanon: Interview with Rima Malek

Responding to COVID-19 in the Bahamas: Interview with Marcellus C. Taylor

I would love to see the English materials you developed and also see if there is a way to assist with the translation of key information into local languages.

Hi Paul…. I’ll email you.

Best wishes

Andy Smart