This blog was written by the Education Commission and first published on the Education Commission website on 24 April 2020.

As of April 24, 2020, schools in over 190 countries around the world have closed due to the COVID-19 pandemic, impacting over 91 percent of enrolled learners and 63 million teachers worldwide. Although schools are closed, learning must not stop. The world’s teachers and the wider education workforce – school leaders, district education officers, policymakers, as well as parents and volunteers – are fundamental to this effort. Now more than ever before, it will take teams to educate our children.

The Education Commission’s Transforming the Education Workforce report provides guidance on education workforce issues that governments can consider as part of their COVID-19 responses. These three visions can help shape responses to school closures, school re-openings, and long-term school disruptions.

Vision 1: Strengthening the education workforce

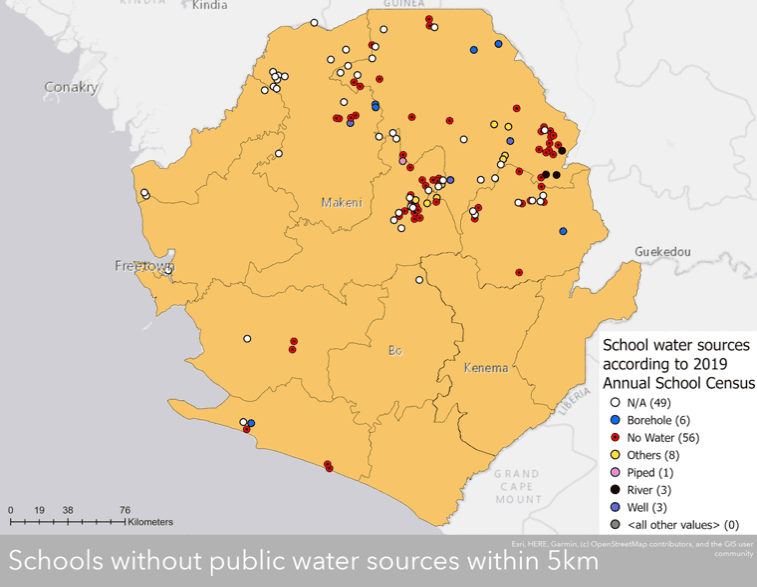

Protect, support, and recognize teachers during the crisis – as called for by UNESCO’s International Task Force on Teachers. This includes preserving employment and wages; prioritizing teachers’ and learners’ health, safety, and well-being; and including teachers in developing COVID-19 education and aid responses. Data should be used to prioritize support to teachers and students with the greatest needs. In Sierra Leone, the Education Workforce Initiative used GIS and school census data to identify vulnerable schools without nearby water sources and provide targeted support.

Source: Fab Inc. 2020, data from https://www.waterpointdata.org/ combined with 2019 Sierra Leone Annual School Census data to show answers schools gave in terms of their water source.

- Provide best-practice professional support for new types of flexible learning, including high-tech, low-tech, and no-tech distance learning relevant to the context. Remote support proved cost-effective and successful in the state of Ceará, Brazil where teachers were given expert educational coaching through one-on-one Skype sessions. In South Africa, virtual coaching via low-tech options like instant messaging, one-on-one text messaging, and telephone calls were shown to positively impact teaching and learning. The Harvard Graduate School of Education and OECD suggest building partnerships between schools and higher education institutions as a way to augment the capacity of districts and school systems to provide ‘just in time’ professional development to teachers and parents.

- Recognize key roles beyond teachers such as school leaders and district education officials who play vital leadership roles. They need regular communication with the government to understand what is expected of them and how to support students, teachers, and parents. Global School Leaders provide examples of how school leaders around the world are responding to the crisis.

Vision 2: Developing learning teams

- Use learning teams to help facilitate a coordinated response so no child is left behind. Learning teams leverage the existing expertise and human capacity of the entire system – teachers, school leaders, support staff, trainee teachers, parents, community volunteers, and others working together (remotely, if necessary) to support learning. This requires clear roles and expectations of each team member, regular communication and support, and coordinated teamwork to ensure that every child is learning. Education Development Trust suggests building teams could include redeploying existing roles in new ways, such as using supervisors or inspectors to review the resource delivery arrangements of schools or tasking curriculum teams with the development of remote assessment.

- Leverage dedicated community workers – trained education volunteers, members of a community-based organization or national service program, or community health workers – to provide additional support around inclusion and well-being for the most vulnerable children, especially girls. In sub-Saharan Africa, Camfed Learner Guides – young women mentors from the community – deliver pastoral curriculum focused on psycho-social, health, and welfare issues. They create an important home-school link, following up with children who drop out and working with communities to keep vulnerable girls safe from child marriage. The program has improved outcomes for students, especially girls. Countries should use school closures as an opportunity to leverage community workers to increase parental engagement in student learning and deepen parent-educator relationships.

- Support teamwork and collaboration with appropriate structures and practices. Studies show that peer and professional learning communities can support improved teaching and learner outcomes and motivation but need formal support from a school or district leader, strong facilitation, access to expertise, and the ability to harness social media.

Harnessing new workforce design to help respond to COVID-19

EWI in partnership with PwC Ghana is supporting the Ghana Education Service (GES) to redesign the structure of its education workforce at national, regional, district, and school levels in response to the pandemic. The government is planning to take a far more cross-cutting and mainstreamed approach to edtech and digitization across the Ministry as well as a more cross-sectoral approach. To ensure learning continues, this is now high priority and the GES has created an interdisciplinary and interagency team to produce curriculum, design activities, and scope and sequence content.

Vision 3: Transforming education systems into learning systems

- Test innovative learning configurations, including technology-assisted learning, to better address individual learning needs and give learners access to a wider variety of knowledge sources and ways of learning. The COVID-19 crisis is driving a shift in this direction, but equitable access to these new learning configurations, the ecosystem required to support them, and evidence on what does and doesn’t work should inform current and future redesign of learning experiences.

- Develop school networks and harness system leaders to enable teachers, schools, and districts to exchange evidence and knowledge about effective instruction and management as schools and districts rapidly test new approaches and assess whether they work. Information sharing across networks can help accelerate improvements and innovations as systems grapple with new ways to ensure children continue to learn.

- Collaborate across sectors, particularly with health and the private sector. The Brookings Institution urges the education workforce to consistently disseminate life-saving COVID-19 public health messages and training throughout education activities. Teams of teachers and health workers could support this, especially to the most vulnerable families. Cross-sectoral collaboration should also include leveraging the expertise and resources of the private sector – telecom and media companies, tech producers, etc.

The current crisis is forcing all countries to strategize how to accelerate the transformation of education systems into more resilient and flexible learning systems. Countries should seize this opportunity as they plan for the reopening of schools, remediation, and building of more robust infrastructure and capacity. As the former Liberian Minister of Education George Werner recently suggested, big opportunities for radical reforms don’t come along very often: “[W]hen schools do finally reopen, Ministers need to recognize the reform moment it represents… [t]he challenges will be starker than ever: traumatized students and school staff, overcrowded classrooms, months of missed content to catch-up on. But there will also be the political will to do some radical things, and to pay for them.”

If you are undertaking research on the effectiveness of these approaches as part of the COVID-19 response, please let us know: info@educationcommission.org

Good road map to recovery after the pandemic. It calls for robust selflessness approach from all the players for its effectiveness.

With commitment and determination the time lost will be harnessed amicably.